On Easter Monday 1916 Irish nationalists launched an armed revolt against British rule in Ireland. One of those involved in suppressing the rebellion was Brigadier General Ernest Maconchy whose unpublished memoirs shed light on this seminal moment in Irish history.

Easter Rising

The Easter Rising took place against a backdrop of increased political tension. This was caused by British reluctance to implement Home Rule, enacted by the 1914 Government of Ireland Act, and their assertion that it could only be done if conscription was also introduced to Ireland.

This linking of conscription and Home Rule outraged Irish nationalists of all persuasions. But the militant Irish Republican Brotherhood, along with sections of the Irish Volunteers and Irish Citizen Army, opted for a violent response.

British response

The revolt came as something of a shock to the British, whose intelligence mistakenly believed the plot had been postponed following the Royal Navy’s interception of smuggled German weapons. It took the better part of a day to organise a response, which was inevitably armed.

Troops were rushed from elsewhere in Ireland and sent from Britain, including Maconchy’s Sherwood Forester Brigade which landed just south of Dublin at Kingstown (now Dún Laoghaire) on Tuesday 25 April 1916. He wrote:

‘Matters seemed to be very serious. The Irish Command HQ had moved into the Royal Hospital Kilmainham, and the few Regular troops in Dublin and those brought up from the Curragh [in County Kildare] were having severe fighting. The route into Dublin from Balls Bridge onwards… was strongly held… no arrangements had been made to cope with it; everyone in authority appeared to have gone on leave to England, the Sinn Feiners were allowed to wear uniform and occupy strategic positions.

My orders were… to advance with two battalions direct via Balls Bridge, Northumberland Road and Merrion Square… I marched off with the 2/7th and 2/8th [Battalions of The Sherwood Foresters] at 10am and on the way heard that there was a bombing school which we should pass. This was indeed a find, as we had no bombs and on reaching it I sent for the chief instructor. He and his officers placed their resources at our disposal… Various officers in uniform who were on leave from units in France met me on the way and asked to join the Brigade… No opposition was met for several miles and the people appeared perfectly friendly.’

Dublin street fighting

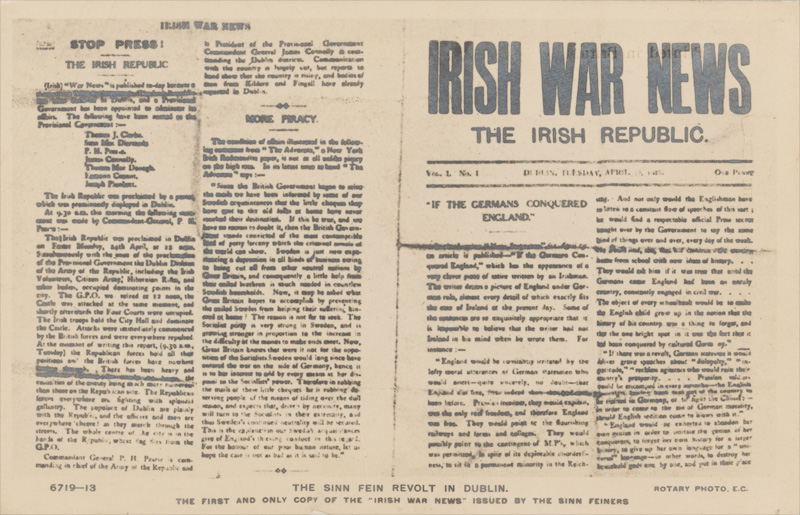

Martial law was declared across Ireland, but the fighting was largely confined to Dublin. It focused around the General Post Office building, where the rebels proclaimed the establishment of the Irish Republic. Maconchy described the struggle:

‘Balls Bridge was reached at noon and as the advanced guard crossed a heavy fire was opened on them from the front (Pembroke Road) and the flank. It was a trying ordeal for such young troops of whom many had only three months’ service, especially as it was impossible to see where the enemy, who were concealed in the houses, were firing from. I ordered the 2/7th to advance up Northumberland Road and take the strong position which formed a bridgehead at the end of the street. When this was taken the 2/8th were to pass through the captured position and advance up Lower Mount Street towards Merrion Square and College Green.

The 2/7th aided by the officers from the bombing school, bombed in the doors or houses occupied by the enemy and drove them out, but the battalion continued to lose men heavily, all along Northumberland Road. The corner house in Haddington Road was strongly held, and only taken after a most gallant attack in which several lives were lost. As the afternoon wore on the battalion’s losses mounted up. Captain Rayner with a few men had crossed the bridge under a heavy fire but was unable to maintain his position owing to the fire from a barricaded house (Clanwilliam House) almost facing the bridge on the opposite side, and the fire from some schools on the right.

There were nearly 80 casualties amongst the other ranks. A house in Northumberland Road was occupied as a dressing station and throughout the afternoon a Red Cross ambulance with a lady, Mrs Chaytor, all honour to her, sitting beside the driver, drove continually under heavy fire to the dressing station and removed wounded men to hospitals in Dublin. Women also rushed out of houses and dragged the wounded into safety.’

Worse than anything in France

At dusk, Maconchy made another attempt to take the position:

‘The [2/8th] battalion formed up under a desultory fire and when all was ready I gave the order to charge. They dashed forward through a heavy fire being joined by the officers and men of the 2/7th as they went. The attached officers whom I had picked up, afterwards said that it was worse than anything they had been through in France. The schools were taken by 7.30pm and an attempt was made to storm the house on the further side of the bridge but Lieutenant Daffen who led across the bridge was killed and Second Lieutenant Browne so severely wounded that he died of his wounds next day. Colonel Cates then sent for the reserve company as “B” Company as a fighting unit had practically ceased to exist, all its officers, its sergeant-major and all the sergeants being either killed or wounded.

A most gallant charge was then made across the bridge led by Captain Quibell 2/8th who with Lieutenant Foster succeeded in entering the house on the other side by breaking a window and with the aid of bombs attacked the defenders, Lieutenant Foster bayoneting three men on the stairs. The house then caught fire and lit up the whole neighbourhood. This seems to have finished resistance and firing died down.

I went forward and up Lower Mount Street into Merrion Square from where I sent an officer to report to Irish Command that the position had been carried and that the route through to Merrion Square was clear… In the action the casualties sustained by the brigade in this one street were 4 officers killed, 12 wounded, 20 other ranks killed 118 wounded… It is not possible to estimate the casualties of the Sinn Feiners as they were taken away by their friends, but they were probably few as they were under cover. About 20 prisoners were taken in houses captured.’

The rebels were slowly driven back in violent street fighting.

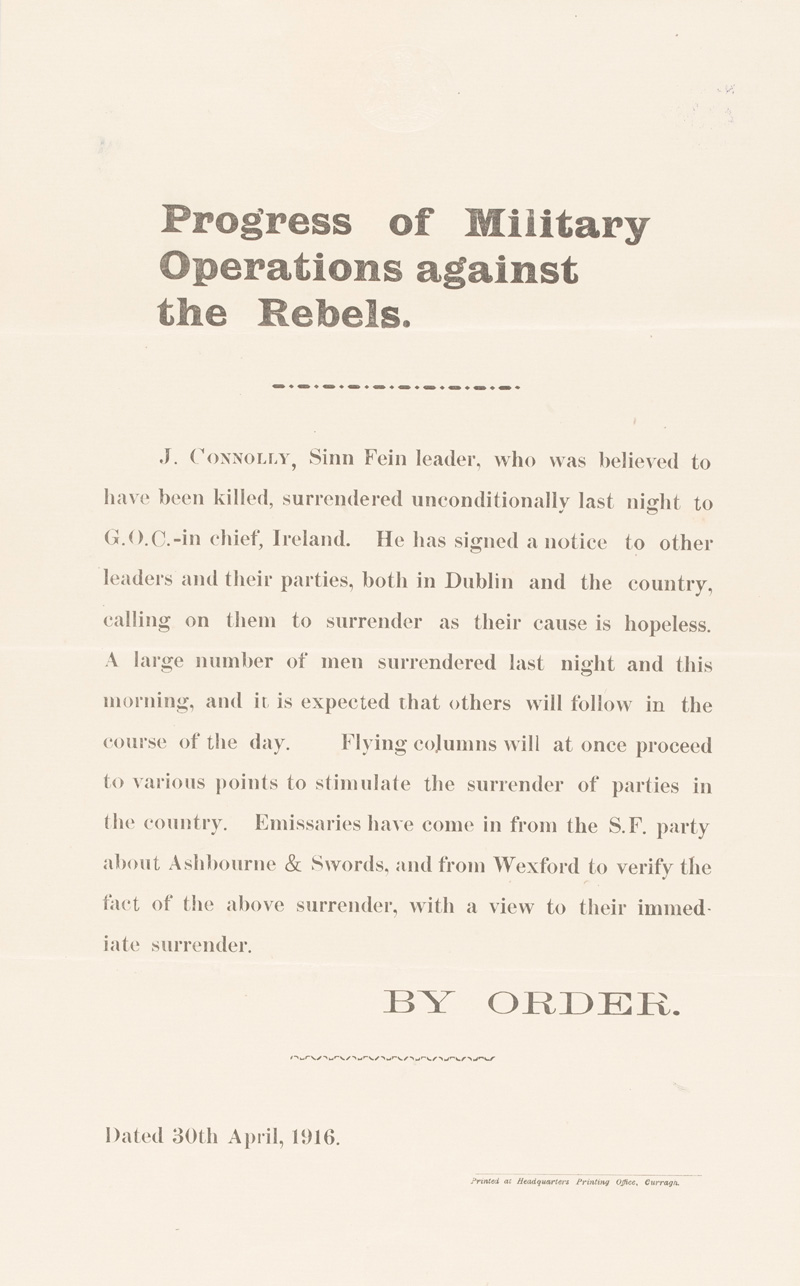

Collapse of the rebellion

The next day, Maconchy’s troops engaged rebels at ‘the South Dublin Union (Workhouse) [now St James’s Hospital] which was flying the Sinn Fein flag and occupied by the enemy [until] a breach in the wall was made and a portion of the building occupied… The city was divided into quarters and the Sinn Feiners steadily pushed into one area, all exits from which were closed.’ Eventually only the General Post Office remained in their hands.

The arrival of British infantry reinforcements and light artillery ended the siege.

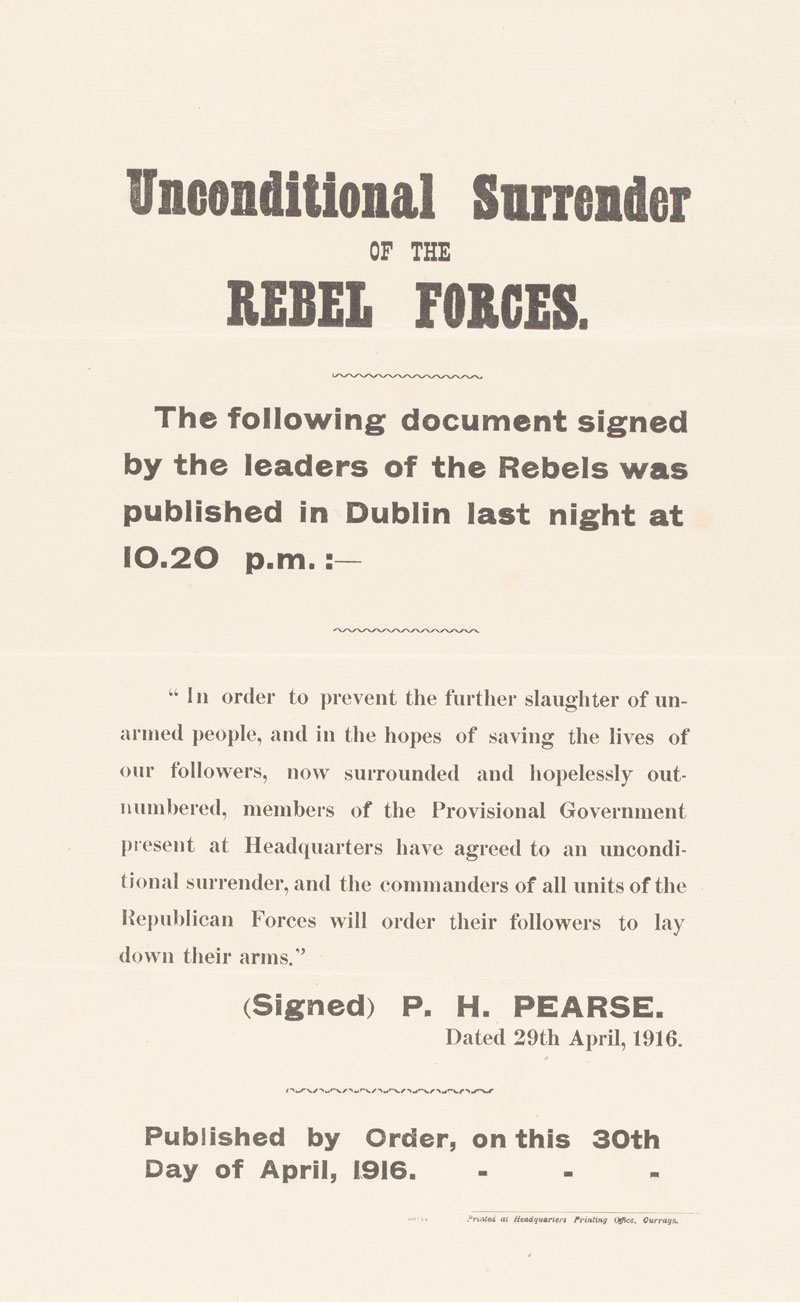

‘On Saturday the 29th April the rebellion collapsed and firing almost ceased in the afternoon. Prisoners began to come in in large numbers.’

British losses were 120 killed and nearly 400 wounded. Around 60 men from the Irish Volunteers and Irish Citizen Army were killed during the revolt. Over 180 civilians also died.

Public opinion

The rising lacked wide-scale public support at its outset, and not only among Unionists opposed to Irish independence. Many Dubliners had relatives fighting in the British Army and felt it was a betrayal of them; others objected to the violence used by some rebels and to the disruption to food supplies. ‘There was considerable shortage of food in Dublin and bread carts were looted by hungry mobs.’

Maconchy believed ‘the general feeling of the people was against the Sinn Feiners’. This ‘was clear from the fact that they streamed out from alleys and courtyards and cheered… as I went up Lower Mount Street… The residents [also] very kindly provided us with food and beds.’

Some people saw the violence as an opportunity to loot shops. Others watched the fighting with a mixture of indifference and curiosity.

‘Mothers held their children up at the windows of houses to see the soldiers… and maids came out of the houses to watch the fight, regardless of the bullets which were flying about very freely, only to scream and throw their aprons over their heads and run in when a bullet came unpleasantly close.’

Maconchy noted though that as the fighting wore on ‘the whole country wished to be at peace and was disgusted at the destruction that had been wrought’.

Executions and internments

The subsequent British military occupation of the city and the internment of over 1,400 Republicans, many of whom had little do with the rising, angered many and increased electoral support for Sinn Féin. Most importantly, the British reprisals against the revolt’s leaders, 16 of whom were executed, generated sympathy for Republican ideas.

Maconchy presided over the Dublin trials of some of the insurgents:

‘Late at night on the 2nd May I received orders to have three of the ringleaders of the rebellion shot at dawn. The instructions were in great detail but on going carefully through them, nowhere could I see anyone’s signature to the orders and therefore refused to carry them out until they were signed by someone having authority to do so. This was eventually done and the orders carried out. On the 3rd I was appointed president of one of the two Field General Court Martials to try prisoners, although I protested to Sir John Maxwell, as I was an Irishman.

We tried a very large number. There could be no doubt, on the evidence, of the guilt of those brought before us, or of the only sentence permissible but of course it rested with the confirming officer to decide as to the carrying out of the sentence and it is possible that reference was also made to the Cabinet in London. We could only recommend certain cases for mercy. When called on for their defence they generally only convicted themselves out of their own mouths, and in many cases I refused to put down what they said as it only made their cases worse.

During the trial of one of the ringleaders his whole attitude of mind seemed so strange to me that I asked him if he would mind telling me… what he was fighting for. He drew himself up and said, “I was fighting to defend the rights of the people of Ireland”. I then asked him if anyone was attacking those rights and he said, “No, but they might have been”. This seemed a strange excuse for shooting down innocent citizens in the streets, but I presume that that is the fashion in all rebellions against constituted authority. He then made a strong plea for the Irish National Volunteers as they were called, whom he said had been kept in ignorance of the purpose for which they had been called out. This was a fact which was evident from the testimony of the men themselves. I was very much relieved when an officer of the Judge Advocates Department was sent over to take my place.’

Court of Enquiry

Both sides accused each other of atrocities. British soldiers claimed the rebels fired dum-dum (expanding) bullets and used civilians as human shields. The rebels in turn said surrendering volunteers were shot down in cold blood and civilian sympathisers were killed. Maconchy found himself investigating these claims.

‘I was appointed President of a Court of Enquiry on certain alleged acts of violence and killing of civilians by our troops… This was a lengthy affair as it was necessary to take down every scrap of evidence that could be produced… My Brigade was not concerned except in one case which was easy to dispose of… [This occurred] during some severe fighting in North King Street and the only marvel was that a great many innocent people were not killed. As a matter of fact the troops had, at considerable risk to themselves, escorted civilians, women and children, out of the street to places of safety and looked after them.

The trouble really arose from bodies being found buried in cellars and back gardens which gave rise to the idea that men had been foully murdered and secretly buried. The fact was that the colonel of the battalion concerned, a Territorial, had got it into his head that it was the custom of war that men should be buried where they fell and the evidence of his written orders to his sergeant major and of the burying parties were quite sufficient to dispose of the idea that there was any secrecy.

Some men were possibly wrongly shot because they were found with arms on them in houses from which the troops had been fired at and it is also possible that they were carrying arms for their own protection against looters who had been at work in the streets for several days. In the heat of a night fight however troops do not hesitate to shoot down anyone with arms on them.’

Biography

Ernest William Stuart King Maconchy (1860-1945) was born in Exeter, Devon on 18 June 1860. He was the 13th child of George Maconchy of Rathmore estate, County Longford, and Louisa Elizabeth Maconchy (née Richards), of Bangor Castle, County Down. His parents had moved to England in the 1850s, so Ernest grew up at Caldwell House, near Newton Abbot, and then ‘Corrinagh’ on Warverry Hill in Torquay.

He attended Honiton School, Spencer House School in Wimbledon and Repton College. A keen lawn tennis player, Maconchy won many tournaments in the west of England.

For a short period he worked as a Latin teacher at Bristol Grammar School and from March 1880 served as a second lieutenant in the Royal South Down Militia (later the 5th Royal Irish Rifles).

In January 1882 he was gazetted to 1st Battalion The East Yorkshire Regiment, but financial constraints made him apply for the Indian Army as this offered a better chance of living without accruing large debts. Maconchy embarked for India in September 1883 and was posted to the 11th Regiment of Madras Native Infantry. In July 1886 he transferred to the 1st Regiment of Sikh Infantry of the Punjab Frontier Force.

Ernest saw much action on India’s North West Frontier, including the Black Mountain Expedition (1888) and the Hunza Expedition (1891), where he was wounded, mentioned in dispatches by Major General W K Elles and awarded a Distinguished Service Order. In 1895 he served with the Chitral Relief Force, and in 1897 joined the Tirah Expedition.

Maconchy married Caroline Agnes Campbell on 2 November 1895 at St Paul’s, Onslow Square, London. They had two children, George Alexander, born in 1896, and Deborah Agnes, born in 1902.

Promoted to major, he fought in Waziristan in 1901-02 and was appointed Assistant Quarter Master General, Intelligence Branch, at Simla in 1903. The following year he was promoted to lieutenant colonel commanding the 51st Sikhs (Frontier Force). From 1906 until 1909 he worked at the Department of Military Supply, having been promoted to colonel in June 1907.

Maconchy was then Deputy Secretary of the Government of India’s Army Department until 1912. Made a Companion of the Order of the Indian Empire in 1909 and a Companion of the Order of the Bath in 1911, he retired in January 1914, settling at Edenmore in Hook, Hampshire.

Maconchy returned to the colours following the outbreak of war. In October 1914 he was appointed Assistant Adjutant and Quatermaster General of 23rd Division, which was being raised near Farnham. The following July he was made brigadier general commanding 178th Brigade (2nd Sherwood Foresters) of 59th (2nd North Midland) Division, a second line Territorial unit providing drafts for the Army on the Continent.

On the outbreak of revolt in Ireland, 178th Brigade was ordered to Liverpool for embarkation to Kingstown (now Dún Laoghaire), landing there on 25 April 1916. Maconchy’s division remained in Ireland until January 1917.

In December 1915 Maconchy had journeyed to the Western Front with 143rd Brigade in an observatory role, gathering information for training purposes. He returned to England in late January 1916.

In February the following year he joined 59th Division in France which went into the line south of the Somme, near Estrées. He led 178th Brigade at Jeancourt and Le Verguier, but the division’s lack of training and uncertain leadership saw him replaced in April 1917.

Maconchy spent the rest of the war as an inspector of munitions. He was created a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George for his services and retired to his farm at Hook. His son George was killed in action on 14 January 1920 at Ahnai Tangi in Waziristan, while serving as a captain with 2nd Battalion 5th Royal Gurkha Rifles.

Brigadier General Maconchy died on 1 September 1945 and was buried at St Nicholas Churchyard, Newnham, Hampshire.

Explore further

- Article: Other Soldier Stories

Explore the map for similar stories

Brigadier General Ernest Maconchy - Torquay, Devon

First World War in Focus

First World War in Focus