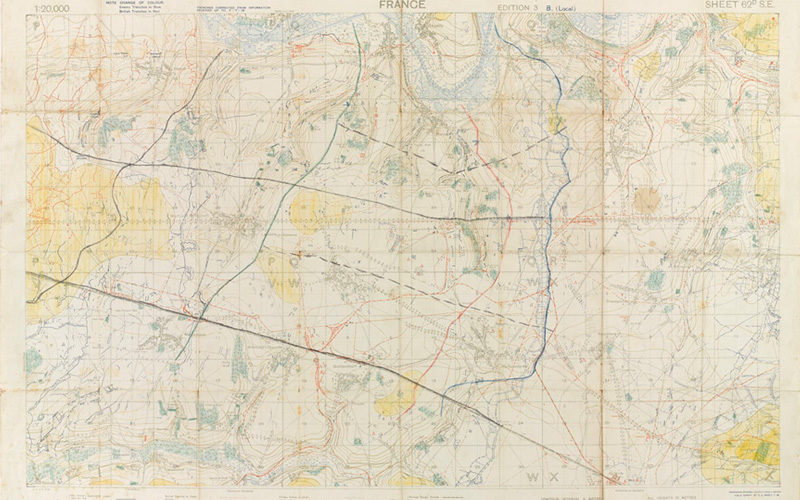

The maps and memoirs of Captain Daniel Hickey of the Tank Corps shed light on the Allied victory at Amiens in August 1918. This struggle helped decide the war on the Western Front and demonstrated that the British Empire forces there had evolved into a highly skilled and effective instrument of war.

Initiative

Germany’s attempts to break through on the Western Front between March and July 1918 had finally ended with the French counter-attack on the Marne. Launched on 18 July, this had forced the exhausted Germans back.

With no victory in sight, and having sustained heavy losses, the morale of Germany’s soldiers now began to waver. The strategic initiative had passed back to the Allies.

Amiens

At 4am on 8 August 1918, General Sir Henry Rawlinson’s Fourth Army launched a major attack at Amiens against the vulnerable salient created by the German offensives. His assault was supported by the French First Army which attacked in the south.

In Fourth Army’s sector, Rawlinson used over 2,000 guns, 450 tanks and 1,900 aircraft to support the attack by 11 divisions (three British, four Canadian, and four Australian).

Many of the German defences had been hastily prepared and were vulnerable to attack. Over 500 of their gun batteries were knocked out by accurate Allied counter-battery fire at the start of the operation, thanks to a combination of sound ranging and aerial observation techniques.

A Mark V tank, of the type used at Amiens, undertakes battle trials, 1918

More details: NAM. 1987-01-60-60

Surprise

To maintain the element of surprise, this attack was not preceded by a large bombardment. Instead, a supporting barrage was immediately fired from 900 guns as the attack went in. The initial assault was also partly concealed by mist. Hickey, who was leading No 7 Section of ‘B’ Company, 8th Tank Battalion, recalled:

‘It was obvious that we were going into a big show. But as everything was being kept secret, I did not know the extent of the battle front. I knew that we would be with the Australians, in a great drive forward… As soon as it became dark on the 7th August we started our approach march. From [map reference] 0.13.ac over the four miles to the Company Point of Assembly… the tanks went, one after the other. As we reached the forward area, a squadron of aeroplanes flew between the lines. This manoeuvre was to drown the noise of the tanks moving up… We waited in darkness and silence. Suddenly at 4.20am (zero hour) our massed artillery opened fire on the whole front of attack. This hurricane bombardment was muffled by the dense ground mist which had risen from the Somme valley and spread like a blanket over the country.’

The attack was spearheaded by the Canadians and Australians. Their aggressive and innovative tactics had been well-honed during several earlier engagements, such as Hamel in July 1918.

Liaison

Hickey was a liaison officer with the Australian infantry and had to guide his three tanks on foot to their targets. Without men like Hickey, tank crews could not communicate with other tanks or with their supporting infantry due to the noise of their machines and the sounds of battle.

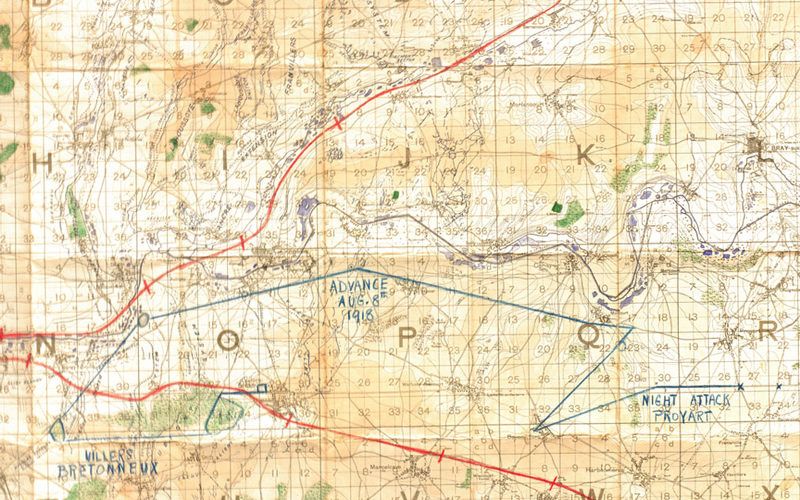

The tanks were to flatten barbed-wire defences or destroy machine-gun posts that might slow up the infantry. Many tanks were fitted with huge bundles of sticks, known as fascines, to be tipped into the deep ditches of the enemy lines. These would form bridges over which the following tanks could crawl. Hickey’s maps show the movements of his tanks during attacks on 8 and 10 August.

‘The attack was divided into two phases. We were in the second, and were to follow in the wake of the tanks and infantry of the first phase, their objectives – known as the Green Line – were to be our jumping off places. The second phase was not to commence until four hours after zero – 8.20am. In the impenetrable mist we started off for our forming-up position… where we were to fall in with the Australians… It was impossible to see where we were going, and it was more by good luck than good guidance that when the mist lifted we found ourselves… in a field where tanks were lined up… The first phase… had been a great success. The enemy had been taken completely by surprise, and tanks and infantry had simply smashed through. Now, at a given signal, we started off in brilliant sunshine across the newly acquired ground towards the Green Line, about two miles ahead.’

More details: NAM. 2006-07-31-4

The assault infantry worked well with the barrage and supporting tanks. But Hickey, walking beside his tanks, soon found himself in a vulnerable position:

‘The pace of the advance was regulated by the progressive lifting of the artillery bombardment from specified places. While other sections had been allotted to particular battalions, mine was more a less a free agent. Its duty was to assist in reducing all strong points on a frontage of about three-quarters of a mile south of the Somme and occupied by two Australian battalions, each of which already had a section of tanks allotted to it. As we started at 8.20am the barrage lifted from the valley in front… Enemy machine-guns were chattering in the woods on the right. I thought we were in for a sticky time…

‘My three tanks separated. H24 went off to the left, H32 to the right; while I went with H25 along a middle course. The infantry, keeping well up with the tanks, were advancing in extended order. About half-way to our objective, while passing on the right of Morcourt, I heard the whizz-whizz, zip-zip of sniper’s bullets. They struck the earth round about me. When I realised that they were meant for me, I took cover in a shell hole. Then I went on. We were now on the crest of a ridge, and I could see across the valley to the next ridge which was our objective. The tanks and infantry were moving forward without a hitch… All this time one could hear the chatter of machine-guns. What surprised me was that the line steadily advanced and that no one fell dead…

‘By 10.20am our infantry were on the Red Line – our objective – the ridge beyond Morcourt, about two miles east from our jumping off place on the Green Line. The work of our tanks was therefore finished, for the infantry were digging themselves in along the top of the ridge.’

However, Hickey’s role in the day’s advance was not yet over. As his men prepared to withdraw to meet other tanks carrying supplies and ammunition forward to them, the following events unfolded:

‘An enemy field gun suddenly burst into action. Each time the gun fired I could see the spurt of flame, hear the scream of the shell, and then the explosion… One of [Captain] Glanville’s tanks was in full view of the gun which was firing at it. The shells were exploding perilously close, and I could see that the tank would be hit pretty soon if it were not withdrawn from its exposed position. As far as I could make out the crew of the tank did not know they were being fired on…

‘I hurried to Glanville and pointed out the danger to him… He replied that there was a machine-gun ahead which was doing mischief. I do not know if he knew exactly where it was, but he was determined to wipe it out. I urged that it was more important for him to get his tank to cover; his infantry were on the Red Line, and the next wave of tanks would deal with the machine-gun ahead. As a matter of fact, the big Mark V Star tanks were leap-frogging through us towards their objective, the Blue Line, which they were to exploit about a mile further on… Suddenly, as I was leaving him, a shell passed over his tank and exploded close to me. I ducked, and this instinctive action saved my life. A fragment of shell struck my back…

‘Glanville now got his tank under cover and the gun stopped firing. My job done I went back to see the Medical Officer who examined my wound and dressed it, telling me that although it looked nasty it was not serious.’

By such methods, the attackers broke the German front. The new light Whippet tanks, armoured cars and cavalry were able to continue the breakthrough. British and French aircraft attacked the Germans as they retreated.

In the days that followed, the Allied advance gradually slowed. German resistance stiffened, the advancing troops outran their supporting artillery and many of the tanks were knocked out by enemy fire or suffered mechanical failure.

More details: NAM. 2006-07-31-3

Hickey’s unit remained in action throughout the battle. On 10 August, he led his section in a poorly planned night attack at Proyart alongside the 37th Australian Battalion. This time, the Germans knew they were coming and the darkness made it hard for the tanks to move safely over the unknown ground. After being bombed by a German plane, the attackers’ presence was revealed to the enemy.

‘He at once put up flares which made the night as bright as day. Then hell was let loose! A withering machine-gun fire was opened on the tanks. The infantry following close behind, being swept by it, took cover in a ditch on the south side of the road. The tanks replied with their 6-pounder and machine-guns, but without effect, for no targets could be seen… The enemy now got his artillery to bear on us, and shells began to explode in the road and on other side of it… The noise was terrific. Machine-gun bullets cracked all round like a thousand whips… one of the tanks was lit up like a blacksmith’s fire by the quantity of bullets striking it…The enemy were using anti-tank rifles and armour piercing bullets.’

Despite the heavy fire, Hickey tried to direct his tanks by ‘battering on the front with my stick to attract the attention of the officer inside’, but was once almost ‘jammed between two tanks as they struggled to turn’. Soon after, one of these tanks was ‘perforated on all sides by armour piercing bullets and all the crew, except two were wounded’.

By this time, the German anti-tank fire had successfully stalled the advancing tanks and the infantry had sustained very heavy losses. The operation was soon called off, with nearly all of Hickey’s men being wounded.

Despite occasional setbacks, like Proyart, the wider campaign continued to succeed. By the end of the battle, on 12 August, a gap of nearly 24km (15 miles) had been punched in the German line south of the Somme.

Black Day

On 8 August, the Fourth Army had taken over 300 guns and 13,000 prisoners while the French captured a further 3,000. That day, total German losses were estimated to be around 30,000. The Allies suffered about 6,500 killed, wounded and missing.

It was the first time that such large-scale capitulations had occurred. The German Commander-in-Chief, General Eric Ludendorff, called it ‘the black day of the German Army’ due to the collapse in morale. Both Ludendorff and the Kaiser now concluded in private that Germany could no longer win the war.

Turning point

Amiens was a turning point in the struggle on the Western Front. The battle illustrated that the British Empire forces had learned how to combine infantry, artillery, tanks, cavalry and aircraft in a co-ordinated ‘all arms’ attack. Hickey’s work with the Australians is a good example of this process in action.

Now a mighty and sophisticated instrument of war, the British, Australian and Canadian force would take the lead in defeating the Germans. Amiens began the period known as the Hundred Days, a continuous series of offensives along the line that drove the Germans back, eventually forcing them to sue for peace.

Canadians escort German prisoners through a communication trench, August 1918

More details: NAM. 2002-02-589-112

Biography

Daniel Edgar Hickey (1895-1976) was born in Buenos Aires on 24 March 1895. He was the son of DJ Hickey of the Buenos Aires Great Southern Railway Company, one of several British-owned companies that built and operated railway networks in Argentina.

In 1910, he travelled to Britain for his education, attending Haileybury School. Hickey later graduated from the University of London with a First Class Degree in Spanish. While studying there, he also joined the University of London’s Officer Training Corps (OTC).

In 1915, he was commissioned from the OTC as a second lieutenant with the Suffolk Regiment. But in November of that year, he was on the way back from manoeuvres on the Gog Magog Hills when he crashed his motorcycle.

After two months in the First Eastern General Military Hospital at Cambridge, Hickey was passed for light duties in England. He then attended several instruction courses at the School of Musketry at Hythe, and the Machine Gun School at Grantham.

Hickey transferred to the Tank Corps – then known as the Heavy Branch of the Machine Gun Corps – in December 1916. After training at Bovington Camp in Dorset, he arrived in France on 22 August 1917. He had been promoted to lieutenant in April of that year, and acting captain in early August.

Hickey first went into action in October at the Battle of Passchendaele (1917). In December 1917, he took part in the mass tank attack at Cambrai, where his section captured the village of Fontaine-Notre-Dame.

When the Germans counter-attacked at Cambrai, Hickey was second-in-command of a group of tanks that drove the enemy from Gauche Wood, an action that was mentioned by General Sir Douglas Haig in his official despatches. Hickey’s tanks also covered the retreat of the 2nd Division during the German Spring Offensive in March 1918.

Hickey was posted back to England at the end of August 1918 as part of a training cadre for the 20th Tank Battalion, then being raised at Bovington. He left the service in January 1919.

After the war, he worked as a chartered accountant and lived with his sister Annie at Park Avenue, Golders Green, London, NW11. In 1929, he married Elsie McGuffin of Belfast. The couple later resided at 48 Somerset Road, Wimbledon Common, London SW19.

Hickey later worked as a sub-editor for BBC Southern European News in 1941. As well as writing his memoirs, he was the author of several plays in the 1930s, including ‘Youth in Armour’ and ‘Over the Top’.

He later settled at 38 Westfield Road, Lymington, Hampshire, where he died on 18 January 1976.

Explore further

- Article: Explore more Soldier Stories

- Article: Operation Michael

- Article: Battle of the Lys

- Article: Third Battle of the Aisne

- Article: Explore more First World War stories

Explore the map for similar stories

Captain Daniel Hickey - Lymington, Hampshire

First World War in Focus

First World War in Focus