Major Allen Holford-Walker was a tank commander during the Battle of the Somme and was involved in planning how tanks could be used at the Battle of the Ancre. His papers demonstrate how the British struggled to make the most of their new weapon.

Final attack on the Somme

By the Autumn of 1916, the British Army had made gains to the south of the Somme front, but had been less successful in the north. With the weather worsening, the British were keen to press their advantage over the tired German Army and strengthen their positions during the winter. At Ancre in November they launched their last major offensive on the Somme.

New weapon

The development of tanks had been a closely guarded secret and came about in an attempt to find a mechanical solution to trench warfare. Extensive trials had proved successful and 100 machines were ordered. Men recruited from across the Army learnt how to operate the tank in secret training camps at Bisley and later at Elveden in Suffolk. A new Heavy Section of the Machine Gun Corps was established to operate this new weapon.

From May 1916 Major Allen Holford-Walker oversaw tank training at Bisley and Elveden. He commanded C Company of the new tank corps and recruited his younger brother Archie (also known as Bruce) to captain one of his tank crews. On 26 July 1916, King George V inspected the tanks at Elveden and rode in the tank commanded by Archie Holford-Walker. At Archie’s request, the driver gave the King a bumpy ride.

By the end of July 1916, the British commander-in-chief, General Sir Douglas Haig, had decided that the first group of tanks would go to France to assist in the Somme offensive. In August 1916, Allen’s company secretly made their way to France, and conducted covert training well behind the lines. However, he felt that his men and machines were unprepared for battle.

Flers

Tanks were first used in September 1916 at the Battle of Flers-Courcelette. It was intended that the tanks would cross no-man’s land, destroying machine-gun emplacements, wire and dugouts in the process. They would lead the assault, allowing the infantry behind to push on and secure their objectives.

Major Allen Holford-Walker was in command of C Company during the battle. Under his command was his brother Archie, who captained the tank C19, also known as ‘Clan Leslie’, and oversaw all three tanks attached to the 6th Division during the offensive.

When the battle began on 15 September, one tank broke down as they made their way up to the start line. ‘Clan Leslie’ also suffered damage to its tail assembly and could not continue. But the Holford-Walker brothers ensured that the third tank could make it into battle, arranging for fuel to be brought forward in Allen’s staff car.

Mark I tanks filling with petrol at Chimpanzee Valley, 15 September 1916

More details: NAM. 1952-01-33-55-89

When the attack commenced, only 15 of the 49 tanks taking part were able to move into no-man’s land. C22, the tank refuelled by the Holford-Walkers, made it to a strong point on the German line, known as the Quadrilateral, but struggled under enemy fire and was withdrawn. Allen saw this as a tactical failure and criticised the retreat in the Operational War Diary.

‘Infantry report that he [the commander of C22] did good work, but that he came back too soon. If he had stayed in the Quadrilateral it probably would have been captured and the extensive attacks for subsequent days would not have been needed.’

Allen Holford-Walker (left) and his brothers Archibald (centre) and Leslie, c1914

Courtesy of Alan Holford-Walker

Archie’s tank, ‘Clan Leslie’, could not be repaired in time. But C20, the first tank to break down, took part in the second wave of the attack. It too made it as far as the Quadrilateral and even advanced to the third objective before returning to refuel.

Its captain, George Macpherson, was grievously wounded during the advance and later died. The circumstances of his death remain unclear, but some accounts of the battle suggest he shot himself believing he had failed to do as well as expected.

Although in other places the tanks broke through, they were ultimately too few in number to help secure outright victory at Flers. In a post-war assessment of the operations, Allen wrote that the hastily trained crews had been thrown into the battle at Flers, and the key element of surprise had been wasted.

Ancre

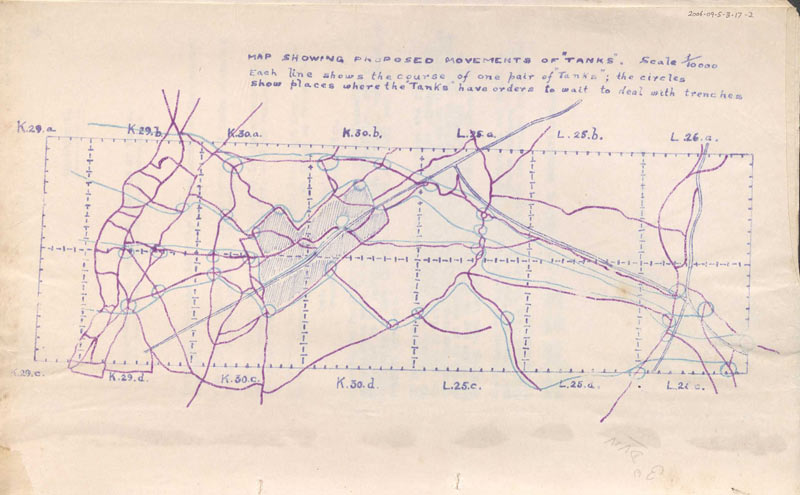

The tank was used again on the Somme in November at the Battle of the Ancre. Allen’s documents show that in an attempt to find a way to exploit the weapon, new tactics were adopted.

The heavy losses on the first day of the Somme had led the British to experiment with new tactics on the battlefield. By September, artillery and infantry were working in coalition, with troops advancing behind a creeping barrage. Unfortunately, the use of tanks caused problems with this method.

At Flers, large gaps were left in the bombardment to make way for the machines, meaning that enemy defences were left intact. In other places, such as High Wood, infantry overtook the slow-moving tanks and found themselves trapped in heavy machine-gun fire, suffering huge losses in the process.

At Ancre, it was decided that the tanks would follow the infantry as this would retain the integrity of the artillery fire, allowing troops to push forward. Allen’s papers show it was emphasised that ‘the Infantry will not wait for the tanks’ in instructions to troops.

Map showing planned tank routes for the Battle of Ancre, November 1916

More details: NAM. 2006-09-5-3-17

This meant that the tanks would instead mop up after the infantry, clearing leftover machine guns and strong points. To retain the element of surprise, the artillery were ordered to cover with shell fire the noise of the tanks making their way to the front line.

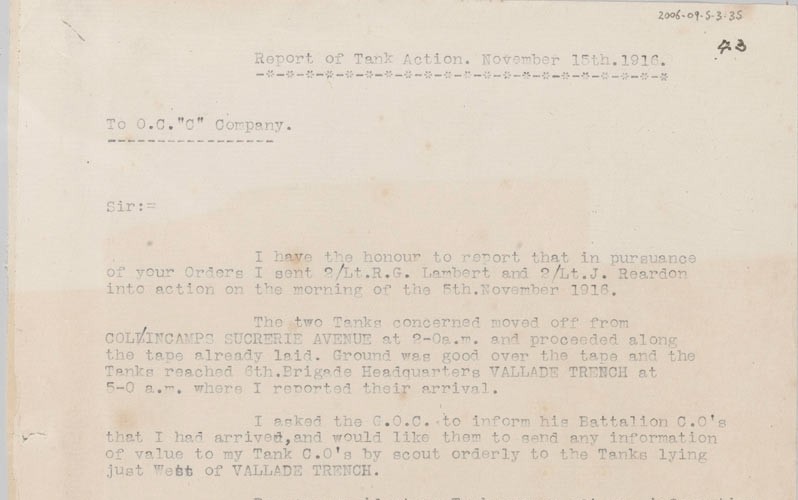

Unfortunately, the tanks themselves were still slow, cumbersome and prone to technical problems. And in the glutinous November Somme mud, they were also vulnerable to getting stuck. This, as Allen’s papers prove, was fateful to the tanks at Ancre.

‘I attribute the fact of the Tanks failing to gain their objective to the extraordinary bad ground they had to cross which was worse than I imagined possible.’

Report by Captain Richard Clively on the tank operations at the Battle of Ancre, 15 November 1915

More details: NAM. 2006-09-5-3-35

Tanks had again proved ineffective at Ancre. But by the end of the battle, British troops had succeeded in capturing Beaumont Hamel. It was not until Cambrai in November 1917, where tanks were used on a mass scale, that they very nearly achieved a breakthrough.

By 1918, the tank was part of a complex all arms battle-plan, using aircraft, artillery and infantry tactics together to ensure victory.

Biography

Allen Holford-Walker (1890-1949) was born on 1 January 1890 in Southend, Essex. He was the eldest son of Brigadier General Edgar Holford-Walker and his wife Maria. Allen had two younger brothers, Leslie and Archibald, and a sister Audrey.

His family had a history of military service. Edgar was in the Royal Artillery he had served in India, and was decorated following the Battle of Tel-El-Kabir (1882). Allen’s uncle George was killed in action in Malaya in 1832. Allen attended the Royal Military College at Sandhurst, graduating in 1909 into 1st Battalion The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders in honour of his mother’s Scottish heritage. He served with them in Malta and India before the First World War.

On 14 December 1914 Allen married Joan Barrington Moody in Farnham, Surrey. Two days earlier he had been promoted to captain.

Allen spent the first months of 1915 training in Alresford, Hampshire, and holidaying with Joan. On 11 May 1915 he was sent to France with the 10th (Service) Battalion of the Argylls. They were part of 27th Brigade in 9th (Scottish) Division.

Prior to departing, Allen is said to have attended a séance, where it was foretold he would be injured in the stomach during the war. To avoid this fate he wore his helmet on his stomach!

While inspecting the Argylls one night, he chose to wear trews (trousers). As Highland battalions traditionally wore kilts, Allen had instructed his troops that men in trousers were the enemy. He was mistaken for a German and attacked with a pickaxe by one of his soldiers.

On 1 July 1915, Allen went into action at Festubert. His unit suffered heavy losses in the attack, and Allen himself was wouded. Admitted to hospital, he returned to England at the end of the month, and remained on sick leave until December. His first daughter Grizel was born on 4 January 1916.

Allen applied to the Motor Machine Gun Service in December 1915, but his application got lost. Instead he was assigned to the Heavy Section of the Machine Gun Corps who operated the tank.

Allen commanded tanks on the Somme from September 1916. After the battle of Ancre in November 1916, he returned to England. He was awarded the Military Cross in the New Year’s Honours of 1917 for his bravery in France. His second daughter Maria was born on 18 January that year.

The Heavy Section of the Machine Gun Corps became the Tank Corps in July 1917. Allen remained with them for the rest of the war. During this time he was regularly admitted to hospital as a result of his previous injuries. He was on sick leave on 11 November 1918, and celebrated the Armistice with his wife Joan in Dorset.

In 1919 Allen rejoined the Argylls. His son Fionn was born on 5 February 1922. He retired from the Army with the honorary rank of lieutenant colonel in 1924.

The next year, Allen and Joan travelled to Kenya. In 1929 they bought a farm there, where Allen raised Ayrshire cattle and owned a pet cheetah named Pong.

Allen briefly returned to England during the Second World War (1939-45). Being too old to fight he advised at the Colonial Office and led passive air defence in Scotland.

On returning to Kenya sickness and war wounds plagued him in later life. He died at his home in Nanyuki on 22 April 1949. Some 100 years after the first tank battle, Allen’s descendants remain in the British Army and are still serving in tanks

Explore further

- Article: Other Soldier Stories

Explore the map for similar stories

Major Allen Holford-Walker - Southend, Essex

First World War in Focus

First World War in Focus