The diary entries of Captain Noel Drury of 6th Battalion The Royal Dublin Fusiliers vividly bring to life the early months of an often forgotten campaign in the Balkans.

The Salonika campaign

Serbia was an ally of Britain and had successfully resisted the attacks of the Austro-Hungarian Army in the first months of the war. But, in October 1915, the combined forces of Austria, Germany and Bulgaria overwhelmed her armies and conquered the country. The Serbs retired through the mountains of Montenegro to Albania, losing over 200,000 men in the winter snow. The survivors were evacuated to the island of Corfu to regroup.

Lack of resources and political indecision amongst the Allies led to delays in the dispatch of aid to Serbia until it was effectively too late to help. It was eventually agreed to land forces at the vital port of Salonika (today’s Thessalonika) in the northern Greek region of Macedonia. Greece was neutral and in some political turmoil, given that King Constantine was pro-German and his Prime Minister, Eleutherios Venizelos, supported the Allies.

French forces and Lieutenant-General Sir Bryan Mahon’s 10th (Irish) Division, exhausted after service at Gallipoli, began landing at Salonika on 5 October 1915. Among the arrivals was Captain Noel Drury of 6th (Service) Battalion The Royal Dublin Fusiliers.

Freezing winter

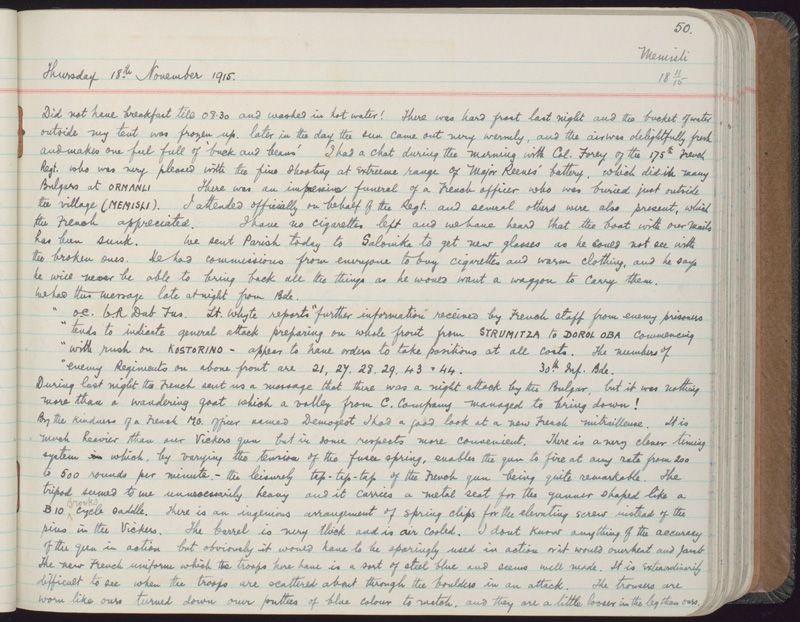

Drury’s unit landed on 11 October and moved ‘up country’ on 29 October to an area north-west of Lake Doiran. En route they passed ‘many unfortunate natives streaming along the road southwards all eager to get away from the invading Bulgars, and trying to carry away as much of their goods as possible’. (Diary entries for 29 October, 8 November 1915)

The 10th Division eventually went into the line in the ‘bare stony mountains’ around Kosturino in November as the Allies attempted to block the Bulgarian advance. Unfortunately, the troops had not been equipped for a winter campaign in difficult mountain terrain. Drury described the conditions:

‘Very bad night – no shelter from the cold and wet. I had a rotten passage round the line, falling and stumbling about in snow drifts up to my shoulders in some places. The snow kept on falling yesterday evening and part of the night, and then changed to a most intense frost. This morning everything is frozen hard and every track is too slippery to walk on. There are now about 2 feet of snow everywhere and much more in some places where drifts have formed. Our overcoats are frozen hard, and when some of the men tried to beat theirs to make them pliable to lie down in they split like matchwood. The men can hardly hold their rifles as their hands freeze to the cold metal. Everyone is falling and tumbling about in the most ludicrous way… We had an enormous sick parade this morning nearly 150 men reporting. There are many bad cases of frost bite in hands and feet.’

By the end of November over 1,600 men had already been evacuated from the division, many suffering from frostbite.

Battle of Kosturino

Apart from artillery exchanges, little fighting took place until 6 December when the Bulgarians attacked following a heavy bombardment. Fighting alongside the French, the 6th Dublins fought off several Bulgarian assaults on their position at Crete Rivet, a prominent hill in front of the British lines. Drury described the Battle of Kosturino:

‘A large mass of Bulgars was creeping up in the fog and were only about 50 yards away. We hastily formed up the men and fired five rounds rapid along the ground into the fog. Almost at the same time we heard B Coy [Company] on our left firing too. We must have got a lot of Bulgars as we could hear their shouts and groans. The Bulgar then charged and we gave them another 5 rounds rapid as they loomed up in the fog. Some of our fellows even got at them with the bayonet. The old Bulgar was so shaken up that he retired into the fog to pull himself together a bit.’

Eventually, the Dublins were forced back, their defence undermined by confused communications as well as the massed Bulgarian attacks. Drury blamed the officer commanding the neighbouring 31st Brigade who was ‘perfectly useless and when I saw him he was mooning about as if he didn’t know nor care what was going on. He doesn’t seem to realise that we are fighting about 10 times our numbers of Bulgars and that only by keeping wide awake will he get his troops safely away’. (Diary entry for 7 December 1915)

His unit had suffered 64 casualties, including eight officers.

The Birdcage

Outnumbered and lacking sufficient artillery, the Anglo-French forces fell back on Salonika. Luckily for them, the Germans prevented the Bulgarians from continuing their advance into Greece, as they still hoped to win the Greeks to their side.

Nevertheless, fearful of a Bulgarian assault on Salonika, and uncertain of neutral Greece, during the first half of 1916 the Allies constructed a fortified line, known as ‘The Birdcage’, in the hills around the city. Drury described the work:

‘We have now started digging a new defensive line. It is very different work from Gallipoli. There we had to dig in anywhere we happened to be whether it was well sited or not, but here we can site our trenches and redoubts so as to give the best field of fire… The work on the trenches, MG [machine-gun] emplacements and redoubts goes on fast. We have done an enormous amount of revetting trenches with brush wood so that they won’t fall in… The wire entanglements are wonderful and I hear that we have used no less than 1,000 miles of wire per mile of front.’

Heat and disease

The Bulgarians did not attack Salonika and the Allies, now re-inforced, were able to advance north and west during 1916. They established a front line that ran from the Albanian coast through northern Greece to the Gulf of Orfano on the Aegean Sea.

This Allied ‘Army of the Orient’ was a multi-national force under French command. French, Serb, Russian and Italian forces manned the western portions of the line and successfully captured Monastir in Serbia on 19 November 1916.

British formations held the area east of the Vardar River, the trenches west of Lake Doiran, and patrolled the Struma Valley to the east. At its utmost, Lieutenant-General George Milne’s force eventually amounted to two corps.

These men faced a boiling summer climate and many succumbed to heatstroke. To counter this, travelling was undertaken at night:

‘The battalion paraded at 17.30 and the head of the column passed the starting point at 18.00. This is the best way to march, in the cool of the evening… [we] bivouacked for the night at 23.00. We remained here [Arakli] during the day on Wednesday… This was a scorching day and easily the hottest we have had yet, but it was a little cooler when we paraded at 17.45… In theory the men rest and sleep till 16.00… actually nobody could possibly sleep in a bivouvac or out of it in this heat with a black swarm of flies buzzing and crawling over everything. I think the flies are almost as bad as at Gallipoli, and being younger are more active!’

British troops in the Struma Valley used cyclists and cavalry to patrol and fortify villages in order to deny them to the Bulgarians and Turks. Both sides evacuated the valley in the summer, owing to the prevalence of diseases like malaria, which caused nearly 480,000 non-battle casualties during the campaign.

Drury succumbed to malaria in July 1916. In his diary he described the journey down to Salonika from the front:

‘About 09.00 a motor convoy arrived and I was shoved on a stretcher and put on the top tier with my face about one foot from the roof that felt like a furnace. It was a terrible journey over awful tracks and I had to keep my hands jammed against the roof of the wagon to prevent my head being battered. What on earth happens to wounded men it is hard to imagine!’

He was eventually evacuated by hospital ship on 27 July 1916.

Serbian liberation

Drury’s battalion remained in the Balkans until September 1917. In April of that year it helped attack the defences around Doiran and on the Vardar as a diversion from the main Franco-Serb offensive to the west. They were repulsed and the main attack also failed.

The front line thereafter remained more or less static until September 1918 when the Allies, now including Greece, launched a new attack at Doiran. Once again the British assault failed, but the Serbs broke through in the mountains to the west. With no reserves and a starving population at home, the Bulgarians were forced into a general retreat, harried by the pursuing Allies. Bulgaria finally signed an armistice on 28 September 1918.

The army in the Balkans was criticised at the time as a waste of men and material, with the troops there having an easy time. However, drained of strength and morale by the harsh conditions, this poorly supplied force managed to bring about a successful conclusion. The campaign ended with the defeat of Bulgaria, liberation of Serbia and strategic exposure of Austria and Turkey.

Biography

Noel Edmund Drury (1884-1975) was born in March 1884. A Dublin protestant, he was the eldest son of John Girdwood Drury. In 1911 he was living in Saggart, County Dublin with his brother Kenneth and their housekeeper.

Following the outbreak of war, Drury volunteered for service and was commissioned as a second lieutenant. He was eventually posted to the 6th (Service) Battalion, which was formed at Naas, County Kildare in August 1914.

His battalion was allotted to 30th Brigade in 10th (Irish) Division. After initial training at the Curragh and Basingstoke, it embarked at Devonport in Plymouth on 11 July 1915 and sailed to Gallipoli. The battalion landed at Suvla Bay on 7 August 1915.

Drury was made temporary lieutenant four days later. His unit went on to fight at Sari Bair, Chocolate Hill and Hill 60. He was appointed temporary captain on 19 September 1915. In early October 1915 his battalion moved via Mudros, on the Aegean island of Lemnos, to Salonika.

After recovering from malaria in Ireland, Drury eventually rejoined his unit, which had moved to Palestine in September 1917. On 3 July 1918 it sailed from Alexandria, arriving at Taranto five days later and then moving by train to France. There it joined 197th Brigade in 66th (2nd East Lancashire) Division. Drury then served on the Western Front until the Armistice, fighting during the ‘Hundred Days’ offensive, including the Battles of the Selle and the Sambre.

In 1919 Drury’s address was 48 Fitzwilliam Square, Dublin. He left the Army in September 1921 with the rank of captain. He died in December 1975, aged 91, in the Dublin suburb of Foxrock and was buried nearby at Deansgrange Cemetery.

Explore

- Article: Other Soldier Stories

Explore the map for similar stories

Captain Noel Drury - Saggart, County Dublin

First World War in Focus

First World War in Focus