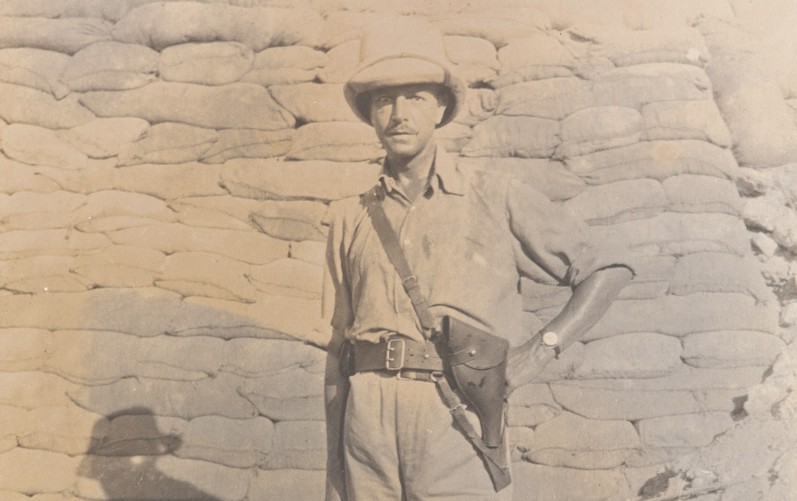

Lieutenant Henry Gallup of 1/5th Hampshire Howitzer Battery, Royal Field Artillery provides an eye-witness account of a defeat in Mesopotamia that shocked the British Empire.

Advance in Mesopotamia

In November 1915 a British-Indian force advancing up the River Tigris in Mesopotamia (now Iraq) was stopped by the Turks at Ctesiphon. So began a chain of events that led to one of the British Empire’s worst defeats of the war.

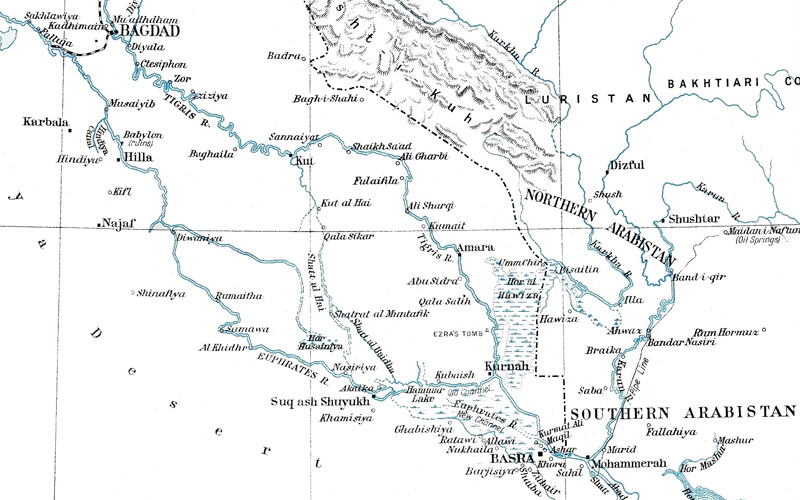

Britain had originally sent troops to the Ottoman province of Mesopotamia to protect its oil supplies, which were at risk following Turkey’s decision to enter the war on Germany’s side. An Indian division occupied the port of Basra in November 1914.

When a second division arrived, the British commander, General Sir John Nixon, advanced deeper into Mesopotamia, where Britain believed a successful campaign would help rally the Arabs against the Turks.

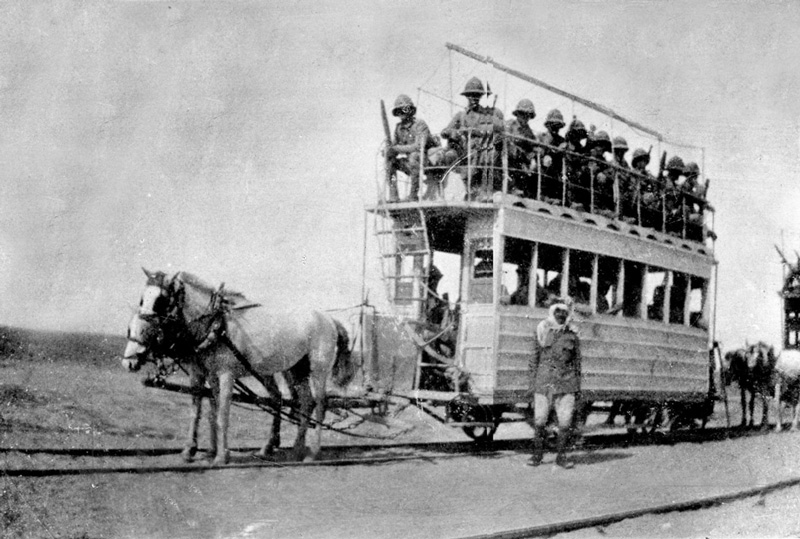

One division moved up the River Euphrates to Nasiriya, while the 6th (Poona) Indian Division, under Major-General Charles Townshend, advanced 160km (100 miles) along the River Tigris to Amara, which he took on 4 June 1915.

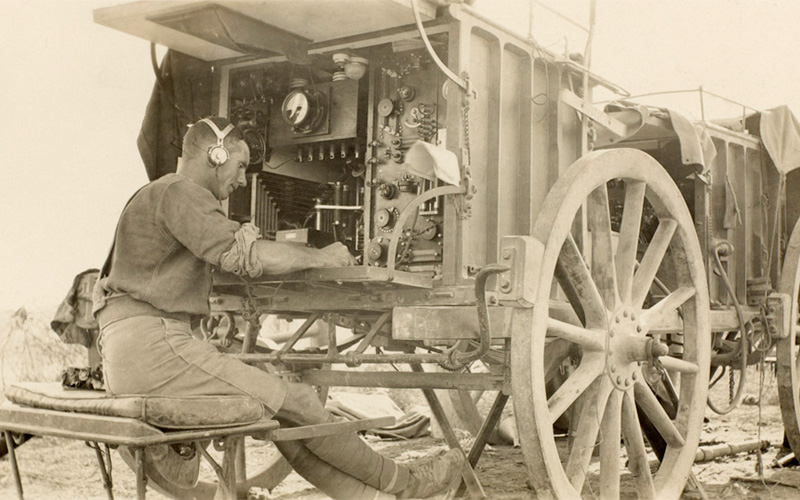

Advancing with Townshend was Lieutenant Henry Gallup of 1/5th Hampshire Howitzer Battery, Royal Field Artillery. His diaries, letters and photographs provide a detailed account of this disastrous episode.

Retreat to Kut

From Amara, Townshend was ordered to push on to Kut, and then to Baghdad, the provincial capital, some 400km (250 miles) away. His division entered Kut on 28 September, having inflicted heavy losses on the Turks. By mid-November it was only 40km (25 miles) from Baghdad.

But a single division was not strong enough for such an operation. Sickness and a lack of artillery, ammunition and supplies had seriously weakened his force. Even if he had been able to capture Baghdad, he did not have the necessary reserves or logistical support to retain it.

On 21-23 November Townshend was blocked at Ctesiphon. Suffering heavy losses, he decided to retreat back to Kut. Lieutenant Gallup described the engagement and retreat:

‘After several hours’ fighting the enemy’s chief position was carried and occupied by our troops, and we then turned our attention to their left flank, where our people were not getting on well at all, and were in fact retiring. It was about 3 o’clock in the afternoon that the Turks counter-attacked so strongly. We found afterwards that they had been re-inforced with about 5,000 fresh troops. The 82nd [Battery] and ourselves were sent forward to try and stop it. I think we managed to do so, for a time anyhow, but it was a very warm time. They then attacked from another quarter and drove our infantry in and we had to limber up and get out as quickly as we could under a most beastly hot fire. We retired to another position and started again and kept them off for some time… It was now getting dusk and I was thankful when we got orders to limber up and retire for the night… I was frightfully weary and utterly sick of the sound of rifle bullets fizzing by… I do not know yet what is the number of casualties but they are heavy on both sides… At 5 o’clock we were rudely awakened by very large bodies of Turks approaching all deployed for the attack. They had apparently been re-inforcing. From then onwards we have been attacked. A very noisy night, heavy rifle firing and things humming over us and most beastly close… It was decided that our force was too weak to hold the position and a retirement was ordered to take place at dawn.’

On 7 December the Turks surrounded Townshend’s 10,000 troops and 3,500 camp followers. For the next few weeks they launched attacks against the defences. Along with the regular shelling, this took a steady toll on the garrison, which only had food and supplies for two and a half months.

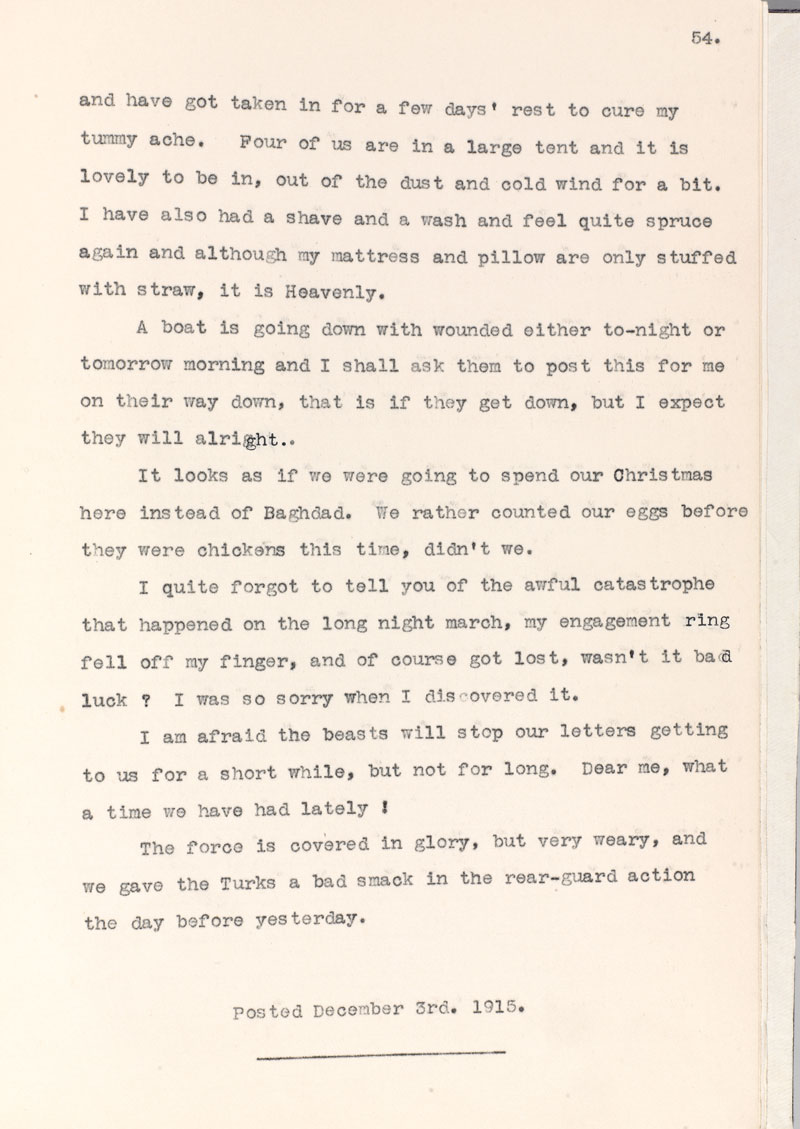

Gallup wrote home: ‘It looks as if we are going to spend our Christmas here instead of Baghdad. We rather counted our eggs before they were chickens this time, didn’t we?’

Published in History of the Great War: Naval Operations (vol 3) by Sir Julian S Corbett, 1923

Under siege

In early January 1916 two Indian divisions, known as the Tigris Corps, were despatched under the command of Lieutenant-General Sir Fenton Aylmer to relieve Townshend’s beleaguered forces.

Tigris Corps rapidly reached Hanna, about 16km (10 miles) from Kut, but was then unable to break through the Turkish defences. Attacks in January, March and April all failed with heavy losses. In attempting to rescue the men in Kut, the relieving force suffered around 23,000 casualties. Gallup described waiting for relief:

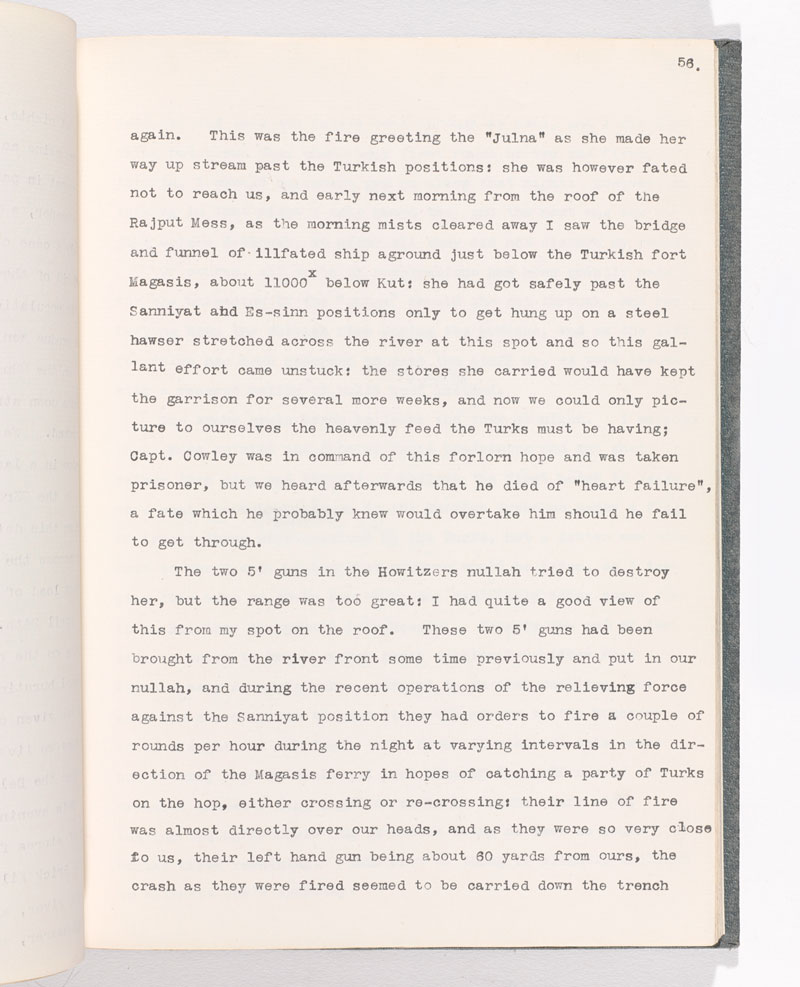

‘On the 22nd [April] Reuters informed us that the Turkish counterattacks downstream had captured much ground. We could still hear much fighting going on in that direction in a last effort to get through to us… This evening [24 April] a most gallant attempt was made to rush a ship load of stores from Wadi through to us after dark. We were up in the Brick Kiln that night listening to heavy fire going on down river, and continued for some time and appearing to be coming nearer, and then all was quiet again. This was the fire greeting the “Julna” as she made her way upstream past the Turkish positions: she was however fated not to reach us, and early next morning… I saw the bridge and funnel of the ill-fated ship aground just below the Turkish fort… the stores she carried would have kept the garrison for several more weeks, and now we can only picture to ourselves the heavenly feed the Turks must be having.’

The garrison slowly starved. Gallup vividly describes the privations of the siege:

‘I can’t tell you how beastly it is to make your breakfast off a plate of indifferent horse or mule: no tea and dinner, instead roast or minced horse and the balance of your piece of bread, and for pudding a very small “Kabob” made of flour and fried in horse fat… I simply long for a piece of chocolate or a tinned apple pudding… It is extraordinary how the idea of food absolutely obsesses one when you can’t get any… Our aeroplanes were working harder than ever dropping sacks of grain, parcels of chocolate, any old thing in fact to enable us to carry on for a few extra days… but however hard the planes worked it was a mighty small allowance that each person got; the planes of course were greeted by heavy fire from the Turkish lines surrounding us… People were getting weaker [and] there was a deal of sickness, especially among the Indian troops who had of course brought a great deal of it on themselves by refusing to eat horseflesh until the last few days; one seldom went into the town without seeing several deaders being brought forth on stretchers for burial from one or other of the hospitals.’

The garrison surrenders

By the end of April the Kut garrison was starving and sickness was rife. With no prospect of relief, Townshend was ordered to begin negotiations with the Turks. At the same time the garrison started to destroy its ammunition and equipment.

‘When these orders arrived I was at once sent off down to the horse lines to see that all the saddles, harnesses, etc was destroyed, this being done I took a party of drivers armed with axes [and] we set to work on our own wagons, breaking the spokes of wheels… On my left hand gun we inserted gun cotton and lit the fuze. We at once hid in the adjacent trench, and in about a minute it went off with a nice dignified bang and split the outer jacket… another charge was inserted and the gun was blown in half.’

On 29 April 1916 the Kut garrison surrendered and 13,000 men, including Gallup, marched into captivity. A third were to die from disease, malnutrition and cruel treatment.

Biography

Henry Curtis Gallup (1874-1942) was born in Bloomsbury, London, on 24 October 1874. He was the son of a wealthy American businessman, Henry Clay Gallup, and his English wife, Lucy.

The family resided at 54 Guildford Street, Bloomsbury, and later Preston House, The Avenue, Gipsy Hill. By 1881 the Gallups had moved to 39 Marine Parade, Brighton, Sussex.

In 1900 Henry was living at Wick House, Downton, near Salisbury in Wiltshire. He was Master of the local Wilton Hunt from 1900 until 1906. That year he moved to Bereleigh House in East Meon, Petersfield, Hampshire.

Gallup was married in 1903 at Downton to Mary Margaret Gladstone. Their children were Henry Clive, Peter Whitfield, Margaret, Nora Lucy and Robin.

On volunteering for service, Gallup was commisioned as a second lieutenant in the Territorial Force on 28 August 1914. After training at Larkhill, he was initially posted to Lucknow in India before being sent to Mesopotamia. His unit, 1/5th Hampshire Howitzer Battery, landed at Basra on 23 March 1915 and joined 6th Indian Division which had arrived in November 1914.

Gallup fought in the Battle of Shaiba in April 1915 and took part in the advance towards Baghdad, including the Battle of Es Sinn and capture of Kut in September. During this service he was briefly hospitalised with jaundice. By November 1915 he was writing home that ‘we are all very fed up with the war and heartily wish it was over’.

Gallup fared better than most of the Kut captives. He ended up at Mosul and later Yozgad, where despite the ‘fleas’, ‘dirty water’ and ‘cramped conditions’ he was able, along with his fellow officers, to purchase enough food to survive. He was repatriated at the end of the war and retired with the rank of major.

After selling his Petersfield estate in 1919 he settled with his family in Brentor, near Tavistock, Devon. Henry Gallup died on 3 November 1942 at Langstone Manor, Brentor.

Explore

- Article: Other Soldier Stories

Explore the map for similar stories

Lieutenant Henry Gallup - Brentor, Devon

First World War in Focus

First World War in Focus