The letters and diary of Lieutenant-Colonel Francis Maxwell show how the British Army on the Somme was learning and improving through experience following the disastrous early days of the campaign.

Learning curve

For many, the attritional struggle on the Somme exemplified futile slaughter and military incompetence. While General Sir Douglas Haig’s tactics were sometimes inflexible and remain controversial to this day, such views ignore the fact that the Somme was a tough lesson for an inexperienced army in how to fight a modern war against a skilled and experienced foe. A more professional and effective force emerged from it.

A good example of this so-called ‘learning curve’ was 18th (Eastern) Division’s capture of Thiepval on 26 September 1916. Lieutenant-Colonel Francis Maxwell played a leading role in this. His account of the operation reveals the difficulties faced by commanders on the spot and how they learnt by experience, whether it was how best to use new weapons like tanks or how to advance behind a creeping barrage.

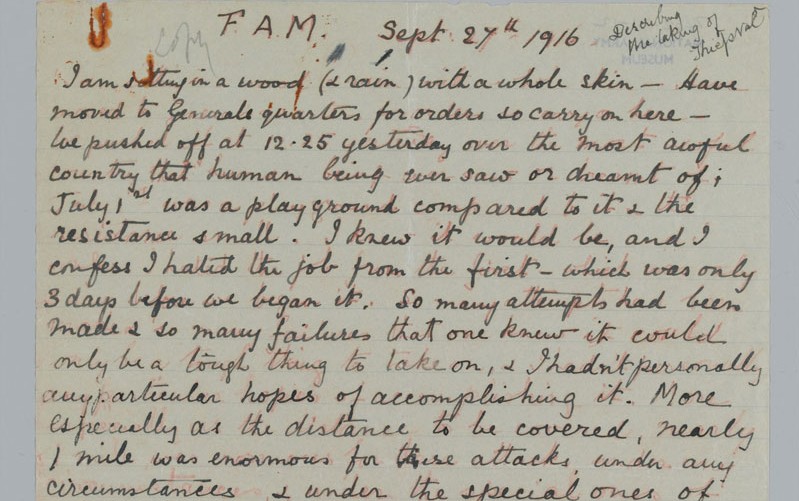

Letter sent by Lieutenant-Colonel Francis Maxwell VC to his wife, 27 September 1916

More details: NAM. 1974-02-31-12

Failure on 1 July

Thiepval and its surrounding high ground had been an objective on the first day of the offensive. On 1 July 1916 it was attacked by the 32nd and 36th Divisions after an artillery barrage that failed to cut paths in the wire or completely destroy German machine gun dug-outs. Despite some initial successes, their assault was beaten off and the fight for Thiepval continued for the next three months.

New attack

On 26 September, four British and Canadian divisions attacked Thiepval again. After capturing the village, its high ground and three defensive redoubts, they were to push forward along the banks of the River Ancre to drive a wedge in the German line. The troops were supported by six tanks, weapons that had made their debut on the Somme just days previously.

Barrage

Unlike the thinly-spread bombardment of 1 July, this time the concentrated firepower of 800 guns targeted the German lines. Maxwell noted that a barrage was ‘always a striking thing to see’:

‘[this] was far more intense because the operation was a limited one in breadth so that there were nearly 600 [sic] guns at work. It is not possible to describe the sight except that it looks like heavy monsoon clouds filled with thousands of fire bursts and the air is rent with the roar of guns and burst of shells.’

Tanks

Maxwell had always been a brave and resourceful officer, but his Somme experiences turned him into one of the finest combat officers of the war. He was particularly concerned with the need for the infantry and tanks to better co-ordinate their efforts:

‘We had two tanks with us, but they failed us as they only could fail in such country; both arrived on the scene behind us not in line with us; one got ditched hopelessly almost immediately and left behind; the other was panting along boldly, but trying to dodge wounded men, lost ground and fell behind and finally got ditched also. I wonder if anyone has learnt the lesson about them… these monsters must precede troops and not follow. Nobody seems to have thought of the wounded men difficulty; some were, I fear, rolled over… I saw in a trench several men buried, three or four sticking out but unable to move’.

Communication problems

Another issue was battlefield communication – something that had hampered earlier Somme attacks. Troops had broken into the German lines but found themselves unable to request reinforcements. Likewise, the high command often had little idea what was happening during attacks.

‘Perhaps the most trying business, wrote Maxwell, ‘is to keep your generals informed of how things are going. It is extraordinarily difficult for on a field like that of Thiepval, telephone lines don’t remain uncut for more then five minutes. And yet they must know things of course, and must get their information by lamp or runners. By lamp it is laborious’ as each ‘message or rather each word is received’. The danger was that ‘the enemy should see the replying lamp’ and ‘put artillery on to its position’. If ‘a message is sent by runner, it means long distances on foot over country already described, and at night as well as by day. By day the runner is usually killed or wounded, by night he gets lost!’

‘A tough thing’

The ground had also been well reconnoitred so the men knew exactly what lay ahead. Maxwell spent three days ‘looking over the ground as far as one could see’. Despite this, the terrain was

‘the most awful country that human beings ever saw or dreamt of; July 1st was a playground compared to it and the resistance small… I confess I hated the job from the first… So many attempts had been made and so many failures that one knew it would be a tough thing to take on, and I hadn’t personally any particular hopes of accomplishing it. More especially as the distance to be covered, nearly one mile, was enormous for these attacks under circumstances… of country absolutely torn with shell for three months’.

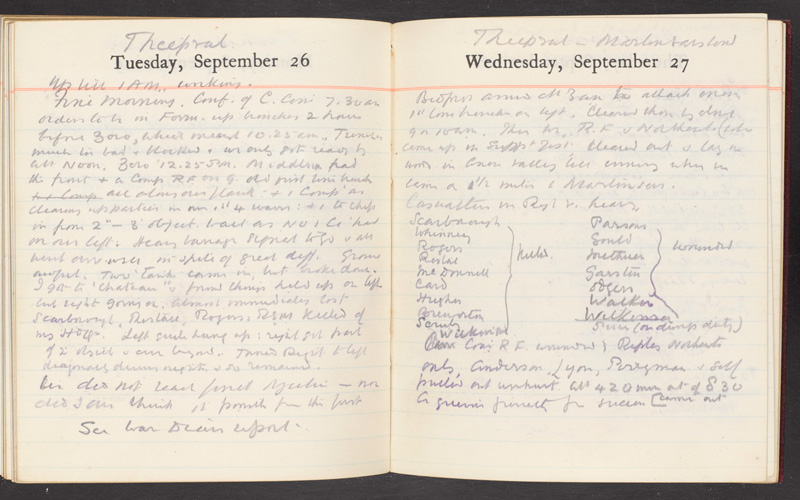

Reconnoitring party before the fall of Thiepval, 26 September 1916

More details: NAM. 2002-02-902-166

Thiepval captured

After a three-day bombardment that cut wire barricades, the attack began in early afternoon, rather than the morning as had usually occurred. This meant the troops could consolidate their final positions in the evening unobserved by enemy artillery as darkness fell.

While the Canadians made progress north-west of Courcelette, 18th Division advanced under a creeping barrage and then fought its way up the heights and through the village only to be held by machine gun fire from the ruins of an old chateau. Maxwell described it as ‘a very strong place filled with machine guns and a determined garrison. This was a thorn in our side indeed. It defied all our efforts to take it’ and had ‘done us in for a large number of casualties’. Two hours later, a tank moved forward and fired into the German entrenchments, before breaking down. A trench mortar was then brought forward to continue the work. After vicious hand-to-hand fighting the British gained control of most of Thiepval.

The losses amongst officers meant that Maxwell eventually found himself leading not just his own battalion, the 12th Middlesex, but also the 11th Royal Fusiliers and 6th Northamptonshires. Rather than wait for orders, Maxwell had taken responsibility on the spot. His men dug in and ‘spent the night either bombing or engaged with the enemy at close quarters’. Eventually Zollern Redoubt was abandoned, and a foothold was seized along the perimeter of the Stuff Redoubt. Most of the Schwaben Redoubt fell the following day.

High price

‘It was an extraordinarily difficult battle to fight owing to every landmark, such as a map shows, being obliterated – absolutely and totally. The ground was of course the limit itself, and progress over it like nothing imaginable. The enemy quite determined to keep us out as they had so many before. And I must say that they fought most stubbornly and bravely: and probably not more than 300-500 put their hands up. They took it out of us badly, but we did ditto, and – I have no shame in saying so, as every German should in my opinion be exterminated – I don’t know that we took one. I have not seen a man or officer yet who did anyway’.

‘We accomplished three quarters of it, and were extraordinarily lucky at that, and it seems to have surprised the high command, which at least is something. But the price has been heavy; how heavy I don’t know as regards men yet, but as regards officers I have, of the 20 who went over, nine killed, seven wounded and four (including myself) untouched… I lost all my regimental staff, with three officers and regimental sergeant major killed’.

Lessons learnt

Maxwell had raised many of the key issues facing the Army. Eventually the right lessons were learnt by soldiers and their generals in how to improve communications and how best to use tanks and other new weapons like Lewis guns, trench mortars and grenades. Artillery tactics improved, with creeping barrages offering closer support to advancing infantry.

Soldiers began to fight in smaller units, with riflemen working closely with those using the new weapons. Some were designated by Maxwell as ‘clearing up parties’ and dealt with the dug-outs that lay behind the advancing troops. The tactics he and others developed on the Somme helped lay the foundations of the Allies’ successful attacks in 1918.

More details: NAM. 1992-12-102-1

Biography

Francis Aylmer Maxwell (1871-1917) was born at ‘Westhill’ The Grange, in Guildford, Surrey, on 7 September 1871. He was the third of 11 children of Surgeon Major Thomas Maxwell of the Indian Army, and his wife Violet Sophia. Francis was educated at the United Services College at Westward Ho! and entered the Royal Military College Sandhurst in 1889.

He was commissioned in the Royal Sussex Regiment in November 1891 and promoted to lieutenant in November 1893. The following year Maxwell transferred to the 24th (Punjab) Regiment of Bengal Infantry and served in Waziristan before taking part in the Chitral Expedition (1895) with the Queen’s Own Corps of Guides and being Mentioned in Despatches for retrieving the body of a fallen comrade under heavy fire.

He later joined the 18th Regiment of Bengal Lancers and served in the Tirah Expedition (1897-8) under General Sir William Lockhart, to whom he was aide-de-camp. He was appointed a Companion of the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) for his services.

Maxwell fought in the Boer War (1899-1902) with Roberts’ Light Horse, taking part in the anti-guerilla campaign. During the latter, his convoy was ambushed at Sanna’s Post on 31 March 1900. ‘The London Gazette’ described what happened:

‘Lieutenant Maxwell was one of three officers not belonging to “Q” Battery, Royal Horse Artillery, specially mentioned by Lord Roberts as having shown the greatest gallantry, and disregard of danger, in carrying out the self-imposed duty of saving the guns of that battery during the affair at Korn Spruit on 31st March, 1900.

This officer went out on five different occasions and assisted, to bring in two guns and three limbers, one of which he Captain Humphreys, and some gunners, dragged in by hand. He also went out with Captain Humphreys and Lieutenant Stirling to try to get the last gun in, and remained there till the attempt was abandoned’.

Maxwell was awarded the Victoria Cross (VC) and promoted to captain. On 14 August 1901, the Duke of York (later King George V), presented him with the VC at Pietermaritzburg. Appointed aide-de-camp to Lieutenant-General Lord Kitchener, Maxwell was promoted to brevet major in August 1902.

When Kitchener became commander-in-chief in India in 1902 Maxwell was again appointed his aide-de-camp. Military appointments in India and Australia followed. From December 1910 until June 1916 he was Military Secretary to Lord Hardinge, the Viceroy of India. Maxwell was created a Companion of the Order of the Star of India in 1911.

In 1906 Maxwell had married Charlotte Alice Hamilton of Currandooley, Australia. In 1907 they had a son Patrick who died only 18 months later. They also had two daughters Rachel, born in 1910 and Violet Winifred, born in 1912.

Appointed brevet lieutenant colonel in November 1915, the following June Maxwell was given command of 12th (Service) Battalion The Duke of Cambridge’s Own (Middlesex Regiment), which had been raised at Mill Hill in September 1914. His tactical acumen and inspired leadership of the battalion helped secure Trônes Wood on 14 July 1916.

Following his exploits on the Somme, Maxwell was awarded a bar to his DSO for ‘conspicuous bravery and leadership’. He was later promoted to brigadier-general commanding 27th Brigade of 9th (Scottish) Division, but was shot dead by a sniper during the Battle of Menin Road Ridge on 21 September 1917. Maxwell had been out reconnoitring a section of ground that was to be attacked.

He was later buried in Ypres Reservoir Cemetery. Maxwell was also commemorated by a plaque at St. Giles Cathedral, Edinburgh, and on the Sandhurst Chapel Memorial, Camberley.

Explore further

- Article: Other Soldier Stories

Explore the map for similar stories

Lieutenant-Colonel Francis Maxwell - Guildford, Surrey

First World War in Focus

First World War in Focus