Second Lieutenant Douglas McKie’s first taste of battle was during the Arras offensive in early April 1917. He was wounded in action and died from his injuries on 11 April 1917, but his photographs and correspondence with his family paint a rich picture of his life and experiences as a soldier.

Early life

Douglas Hamlin McKie was born in 1893 in Bayswater, London. He had two sisters, Helen and Katharine. His parents were Lucy Ann Wernham, a builder’s daughter, and Douglas Allen McKie, a bank clerk. The family initially lived on Thornton Road in Clapham and at some stage moved to Kingston-upon-Thames in Surrey.

Douglas’ collection gives us an insight into his childhood: there are photographs of the family mourning the death of Queen Victoria in 1901, and of the children patriotically waving a union flag atop a rocking horse. There are also several drawings of ships, done by a young Douglas, who would draw his mother a ship for her birthday every year.

Douglas McKie and his sisters, Helen and Katharine, playing on a rocking horse, 1900

More details: NAM. 2005-09-57-1-13

Brazil

Douglas attended Streatham High School and later Tiffin Boys’ School. In 1908, he left education to pursue a career in banking. He took a job at British Law Fire Insurance, working for the father of one of his school friends.

By 1910 he had joined the London County and Westminster Bank as a junior clerk, and by March 1914 he had been given a job as a clerk working for the London and Brazilian Bank in Santos. He departed from Southampton to Brazil on 10 April 1914. Douglas enjoyed a rich social life in Santos, living with a German family and falling in love with a Brazilian girl, Leah Hime. He also took part in sports and expeditions into the jungle.

But even in the rainforest, Douglas could not escape the growing political tensions in Europe. In August 1914, he wrote to his sisters seeking information about recent events. He noted that other French, German and British expatriates in Brazil were returning home because of the war, but was himself sceptical that the conflict would be a long one.

As it became clear that the war was going on longer than he expected, Douglas’ letters sought news of friends who had joined up to fight. In July 1915 he applied to his employer for leave to return to England and join the army.

Artist Rifles

The bank granted Douglas permission to join up and after bidding farewell to Leah he arrived back in the United Kingdom on 28 August 1915. He joined the Artists Rifles, the unofficial regiment for aspiring young officers, as a private. Douglas soon realised that life in the army was distinctly different to life in Brazil, writing to his sister Helen to complain that camp life was cold!

In January 1916 Douglas was injured taking part in a cross-country run during training. While hospitalised in Newcastle he wrote again to Helen about his guilt of being kept out of the war. Citing the famous recruitment poster in his letter, he wrote: ‘What did you do in the War daddy? – jumped over a fence! Seems rather ridiculous doesn’t it?’

Newcastle

Douglas was granted a commission as a second lieutenant with The Northumberland Fusiliers in May 1916. He had long expressed his desire to become an officer, but was unhappy that the new role prolonged his stay in Newcastle, where the unit was based. Douglas also had to endure Zeppelin raids on the city. Worse still, he became ill again, which made his stay in Newcastle even longer.

While recovering in hospital, Douglas often wrote to his family about his desire to return to Brazil, musing that he wanted to be transferred to the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) in order to fly himself back there. Douglas lost his taste for flight, however, when he learned that his school friend Robert Burleigh, who was serving with the RFC, had been killed in action on 29 August 1916. He decided he wanted to serve in a trench mortar battery instead.

Douglas returned to light duties in September, but was hospitalised again a month later. On recovery, he eagerly awaited his dispatch to France in January 1917, but was dismayed to find that he was again deemed unfit for service.

Spring on the Western Front

Meanwhile, on the Western Front the Allies were emerging from a costly year of fighting. In 1916 the British Army had suffered huge losses on the Somme, the French Army had been worn down at Verdun and few gains had been achieved in either operation. A decisive breakthrough still remained elusive.

While the bitterly cold winter months of 1916-17 had brought about a brief lull in the fighting, they also gave the German Army time to review their plans. Germany had also emerged from 1916 in less-than-great shape. The cost of containing Allied offensives had proved higher than anticipated. The German High Command therefore decided on a defensive strategy for 1917 and between February and April they withdrew to a new fortified position known as the Hindenburg Line. It was significantly shorter, protected with pillboxes and deep belts of wire, and gave the German forces a stronger position to defend.

‘The aim of defence in a battle is to make the attacking force fight itself to a standstill and use up its resources in men, while the defenders conserve their strength.’

The political situation of the war had also become precarious. British Prime Minister Herbert Asquith had been ousted in December 1916, due in part to losses on the Somme. The French premier Aristide Briande was likewise replaced in March 1917. Although the United States joined the war on 6 April 1917, American forces would not be deployed in France for another year.

All in all, France or Britain could not afford another disaster and achieving a breakthrough had become imperative.

‘Waiting in trenches near Arras for our creeping barrage to lift before pushing on’, 1917

More details: NAM. 1972-08-67-1-78

The Arras offensive

After months of waiting, Douglas was finally posted to France in March 1917. He arrived just before the British went on the offensive at Arras in April.

The motivation behind the attack at Arras was political, rather than tactical. Initially the Allies had planned a joint spring offensive with the Russians. But this plan fell through when Russia withdrew her commitment to attack on the Eastern Front in February 1917.

In March the French opted to advance along the River Aisne instead. But the German withdrawal to the Hindenburg Line at the same time disrupted France’s battle plans.

Finally, in April Britain decided that they would launch a diversionary attack at Arras. It aimed to draw Germans away from the Aisne so the French could launch a new attack there a week later.

Like many of the previous British battles on the Western Front, the Battle of Arras began with a preliminary bombardment. From 20 March 1917, the artillery began to pound Vimy Ridge. Over a million more shells were used in the bombardment at Arras than at the Battle of the Somme.

The Allies had learnt some valuable lessons from their mistakes on the Somme. Specialised artillery units specifically targeted the German guns through counter-battery fire, neutralising about 80 per cent before the battle.

On 4 April the British extended their fire across the whole 24-mile-long Arras front. They were aware that they could not wipe out the Germans with shells but the extended bombardment exhausted and demoralised enemy troops by pinning them down inside their dugouts without access to rations or supplies.

More details: NAM. 2005-09-57-1-203

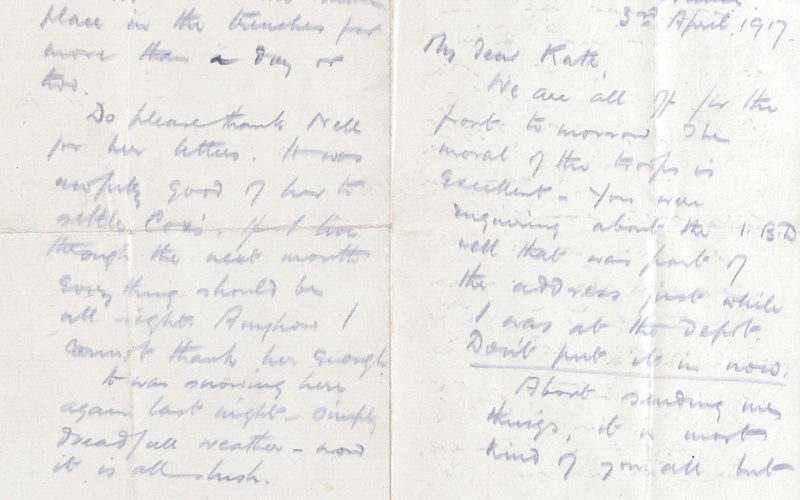

Douglas was evidently also demoralised by the prolonged artillery bombardment. On 3 April he wrote to his sister reporting that he would, reluctantly, be going up to the front line in advance of his attack.

‘Well, my one wish is to be back with a “Blighty” next week. There is absolutely nothing inviting about this part of France at any rate just now.’

The battle begins

The British guns finally fell silent on 8 April. Douglas wrote home describing what it was like in the trenches while the bombardment was going on:

‘I have had my first baptism of fire, a six inch landed a few hundred yards from us yesterday. Our own guns are creating a tremendous row, but placed just beside our billet is rapidly shaking our slate off the roof. My hair oil jumped about a foot from the table when it was firing this morning.’

The same day he was moved up to the front line in advance of the attack. The guns on the Arras front were intentionally kept quiet to confuse the enemy.

At 5.25am on 9 April the guns resumed their fire in a hurricane bombardment. Five minutes later the bombardment stopped and the troops advanced. Weather proved to be an unlikely ally for the British troops as a sudden heavy snowfall blew towards the German lines. British troops succeeded in taking prisoners by surprise in the poor visibility.

The attack initially made good progress, with elements of the First, Third and Fifth Armies advancing up to eight kilometres (five miles) in the first two days.

Douglas however, was less fortunate. On 11 April, the second day of the battle, he was wounded in action, and had died by the time he reached a front-line aid post.

News of Douglas’ death reached his family two days later on 13 April. Upon hearing it, his sister Helen sought ways to piece together the circumstances of his death by writing to friends, and members of his regiment, but had little luck. On 20 April the family received a letter from his commander:

‘I am most distressed to have to write to you about the death of your gallant son. Though he was with us for so short a time he succeeded by his courage and splendid example during the attack in gaining the confidence of his men and the admiration of the Officers over him.’

Aftermath

The Battle of Arras continued until 16 May 1917. The early progress was eventually halted by supply problems as logistical support could not keep up with the advancing troops. Casualties surpassed 150,000 for the British and Canadians and 100,000 for the Germans. Although the Canadian Corps succeeded in taking Vimy Ridge, once again there had been no breakthrough.

Douglas was buried at the Commonwealth War Graves military cemetery at Roclincourt, near Arras. Helen visited his grave after the end of the war, a luxury at the time, as many families could not afford to visit their loved one’s resting place.

Helen McKie standing by the grave of her brother Douglas McKie, 1919

More details: NAM. 2005-09-57-1-226

Helen meticulously collected Douglas’ letters, photographs and documents of his service after his death. Like Douglas, the war also shaped her life. She worked for Bystander Magazine and The Graphic as an illustrator, drawing cartoons of soldiers.

The success of her wartime work eventually earned her an exceptional commission: in 1931 she was invited to Germany by Adolf Hitler to draw him and his staff at the ‘Brown House’ in Munich. She became the only woman to draw the future Fuhrer in his headquarters. A large collection of her work now belongs to the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Explore further

- Article: Other Soldier Stories

Explore the map for similar stories

Second Lieutenant Douglas McKie - Kingston-upon-Thames, Surrey

First World War in Focus

First World War in Focus