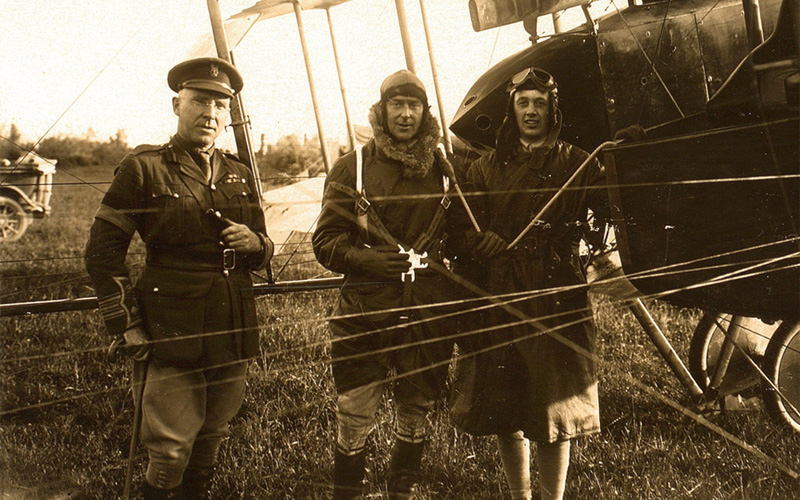

Major John Carter with British and Italian intelligence officers, 1918

More details: NAM. 2004-06-91-2-11

In June 1918, Major John Carter was serving as an intelligence officer in Italy. While there, he was involved in developing new methods of parachuting agents behind enemy lines. His unpublished archives and photographs shed light on this top secret and pioneering mission.

Italian front

Carter was serving with an Anglo-French expeditionary force sent to assist the Italian Army after its defeat at Caporetto in November 1917. Initially, the British contribution consisted of five divisions, but this was reduced to three in April 1918.

British troops played a supporting role during the Italian defence of the Piave in November-December 1917, then in the defeat of the Austrian offensive of June 1918 (the Second Battle of the Piave), and finally in their decisive defeat at the Battle of Vittorio Veneto in October 1918.

Clandestine activities

While most British soldiers were undertaking conventional military duties in these battles, Carter was engaged in more clandestine activities.

During June 1918, he became involved in planning sabotage operations against Austrian war production factories. As part of this, he organised and reported on a series of parachute trials given the codename ‘Tinpot’.

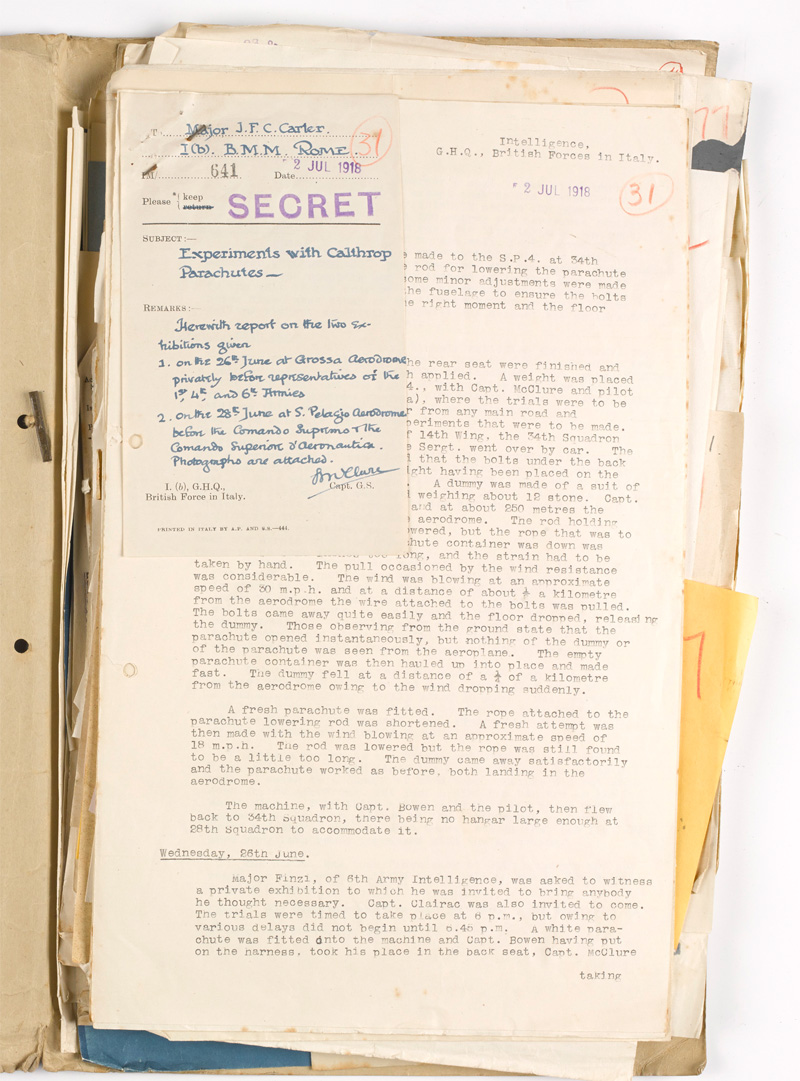

More details: NAM. 2004-06-91-3-2

Parachutes

While many pilots and observers in both aircraft and balloons had started to wear parachutes as a safety precaution, the operational dropping of soldiers or equipment by parachute was a brand new concept.

Carter and his British and Italian colleagues developed a way of dropping a man at low level through the floor of a converted Savoia-Pomilio SP4 reconnaissance and bomber aircraft. They used Everard Calthrop’s ‘Guardian Angel’ parachute, which had been turned down by the Royal Flying Corps in 1916 on the grounds that such a device ‘might impair the fighting spirit of pilots’.

Carter explained how the parachute worked in an SP4:

‘Before leaving the ground the parachute container and supporting rod are pulled up under the forward observers post where they are held by a rope and steadied by a small forked shaped piece of metal. The man-to-be-dropped sits in the back seat with his legs hanging down below the nascelle (the seat is cut away to allow room for his legs). The seat is held in place by two bolts attached by cables to a handle in the forward observation post.

‘Immediately before the man is to be dropped, the parachute container and supporting rod are lowered to the fullest extent of the rope the other end of which is made fast to the machine gun bracket in the forward observer’s post. The pilot then is given the sign to drop the machine’s nose and the bolts supporting the back seat are drawn. The seat under the man-to-be dropped then swings down on its hinges and the man falls clear, pulling out the parachute body from the container as he goes. The empty container is then hauled up into its place under the nascelle… The parachute container has to be lowered before the man so as to prevent the parachute body catching in the bracing wires of the machine.’

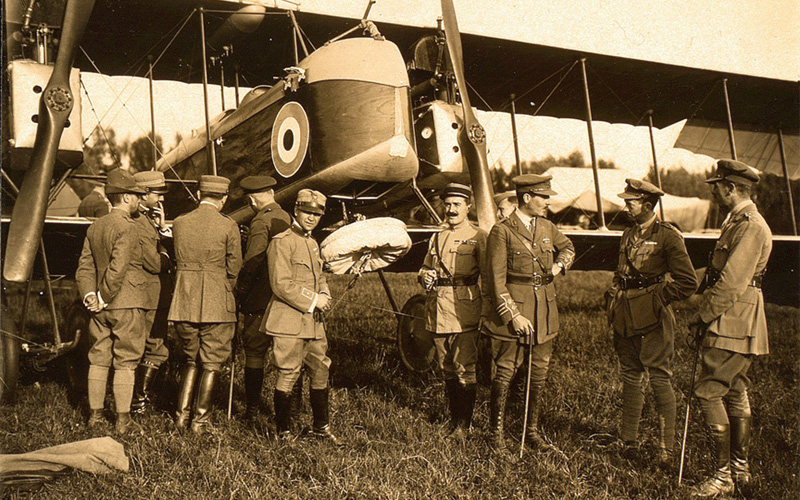

Testing the parachute harness before the drop at Grossa aerodrome, 26 June 1918

More details: NAM. 2004-06-91-3-1

Trials

Secret trials of the equipment were conducted by the Royal Air Force in front of Allied officers at Grossa and San Pelagio aerodromes on 26 and 28 June 1918. Carter sent a series of photographs of the tests with his report to his superiors. His account also demonstrated the dangers of parachuting at low level:

‘At 250 metres the parachute container was lowered, and the strain was taken by the rope. The bolts were released and worked well, Captain Bowen falling in the aerodrome. In some unaccountable way the parachute body was torn on leaving the machine, and the speed of descent was about 23 feet per second instead of 15 feet per second. Also, the rope attached to the parachute got between Captain Bowen’s legs and caused him to turn two somersaults before the parachute opened. Otherwise the descent was satisfactory and Bowen landed safely… Major Finzi [of Italian intelligence] expressed himself satisfied and arranged for some of his agents to be brought down to the aerodrome and instructed in landing.’

The British subsequently began supplying Italian intelligence with parachutes for agent dropping. Carter wrote that they ‘had been thoroughly instructed in the system of dropping agents by mean of parachutes’.

Members of the project also suggested that black parachute silk be substituted for the white used in the trials, no doubt to aid concealment as agents descended into enemy territory under cover of darkness.

More details: NAM. 2004-06-91-3-4

Observers

The trials impressed many of the watching officers. Among them was Lieutenant-Colonel Billy Mitchell of the United States Army Air Service.

No doubt inspired by what he’d witnessed, Mitchell later devised a daring plan for dropping an entire American infantry division behind German lines from a fleet of modified British Handley Page bombers. The war ended before the operation could be executed, but Mitchell continued to champion airborne forces in the post-war years.

Careless talk

Carter’s papers show that he was constantly concerned about any ‘gossip there may have been at the front’ and of the ‘parachute idea being brought into light’. He went on:

‘Personally I am a very great believer in secrecy and I think there is far too much talking in the Army… the thing in itself [ie parachutes] is no secret – the application of them is the secret.’

Incendiaries

Carter’s correspondence also contains references to incendiary or explosive devices. In September 1918, he wrote to a colleague that two military intelligence non-commissioned officers were arriving in Rome from England with ‘ten new parachutes’ and ’20 small incendiary apparatus’. These appear to have been glass tubes ‘with durations between five and six hours’.

Adjusting the harness of Captain McClure before the drop at San Pelagio aerodrome, 28 June 1918

More details: NAM. 2004-06-91-3-12

Mission

Several agents were eventually dropped by SP4 behind Austrian lines, some of whom were equipped with the mysterious ‘tube’ incendiary devices. In August 1918, Carter reported on the first mission:

‘A man was produced from the 8th Italian Army Corps, a lieutenant of Arditi [elite Italian assault troops], a tiny man and absolutely without fear. The night for the attempt was pitch dark and arrangements had to be made for light-houses and signals on the way. [Captain William] Barker piloted the machine (Barker has killed 35 huns), [Captain William] Wedgewood Benn going as observer and manipulator. At 1,200 feet, east of Vittorio, in the vicinity of Saroni, they let the parachute go. Barker saw the parachute open out beautifully and there seems little doubt that the descent was made successfully. The return journey, in spite of the inky darkness and attempts of the enemy to fix them with searchlights, was made in safety.

‘Benn tells me that subsequently, after 4 or 5 days, some photographs were taken of a field in Monticolli a little distance from where the man was dropped. From the photographs there seems every reasonable ground for supposing that our friend landed safely, as certain marks are shown in the photographs which appear to correspond with the prearranged plan of signaling on his arrival. (On landing he was instructed to make his way to another field and place clothes etc on the ground thereby signaling his safe arrival)… Benn is of the opinion that a first class pilot must always be employed… The aeroplane used was an SP4, a big heavy machine, in which if they had been met with very intense anti-aircraft fire they would have been in very serious danger as this type of machine cannot be turned and twisted.’

The agent was Alessandro Tandura. He survived for three months behind enemy lines, providing much useful information and organising sabotage operations. He was twice captured by the Austrians, but managed to escape on both occasions.

Captain McClure descending at San Pelagio aerodrome, 28 June 1918

More details: NAM. 2004-06-91-3-13

Special forces pioneers

The papers show that the concept of parachuting agents or special forces into occupied territory to wage a secret war of sabotage and subversion originated much earlier than usually thought.

The activities of remarkable men like John Carter occurred more than 20 years before the Special Operations Executive were carrying out similar missions.

Biography

John Fillis Carré Carter (1882-1944) was born on 11 January 1882 in the parish of St Luke’s, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada. He was the son of Major Charles Carré Carter of the Royal Engineers.

He was educated at Wellington College and the Royal Military College, Sandhurst. Having passed out as Queen’s Cadet, Carter was commissioned a second lieutenant with the Indian Staff Corps on 28 July 1900. He served in Waziristan on the North West Frontier in 1901-02 and was promoted to lieutenant on 28 October 1902.

Carter was later seconded to the Indian Police Service in Burma in 1905. He was made captain on 28 July 1909, by which time he was serving with the 35th Sikhs back on the North West Frontier.

On 4 August 1914, Carter joined British intelligence. His Indian and police experience soon made him an ideal candidate for MI5’s G section. This was formed to combat possible wartime espionage by Indian nationalists and other revolutionaries in Europe. G section’s main focus was on preventing any subversion of Indian troops serving in the European theatre.

Carter’s files provide a daily record of his intelligence work in London, including meeting named agents and undertaking counter-espionage operations. He also helped uncover a plot by the German-backed Indian Independence Committee to assassinate the Secretary of State for War, Lord Kitchener.

In 1915, he married Gwendoline Marjorie Georges. The couple had two children, John Ralph, who also later joined the Army, and Joan.

Carter left G section on 4 March 1918 for a new posting in Rome with the Special Intelligence Section of the Italian Expeditionary Force. Initially, he was engaged in countering German and Austrian espionage and subversive activity in Italy. But in June 1918, he began work on ‘Tinpot’.

Carter eventually reached the rank of brevet-lieutenant colonel and was twice mentioned in despatches for his wartime services. He joined the Metropolitan Police in 1919, although he didn’t formally retire from the Army until 1921.

Carter worked for the Directorate of Intelligence at Scotland House where he was Assistant Director under Basil Thomson, another veteran of MI5’s G section, and co-responsible for providing regular security reports to the British cabinet.

Carter was then appointed Deputy Assistant Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police in October 1922. The following year, he was appointed a Cavalier of the Order of St Maurice and St Lazarus by the King of Italy. And two years later, he was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire. In June 1925, he was also made a Freeman of the City of London. He was then living at 79 Gunterstone Road in Kensington, London.

In 1933, he took command of No 2 District (North West London). Then, from November 1938 to September 1940, he was Assistant Commissioner ‘A’ of the Metropolitan Police.

In 1939, Carter and his wife were living at Flat 14 Lincoln House, Kensington. He died on 14 July 1944 in Stoneridge, Tavistock, Devon.

Explore further

- Article: Other Soldier Stories

- Article: Explore more First World War stories

Explore the map for similar stories

Major John Carter - Kensington, London

First World War in Focus

First World War in Focus