Sergeant George Johnson, 3rd Battalion, The Duke of Cambridge’s Own (Middlesex Regiment), c1905

More details: NAM. 1992-08-83-1

Captain George Johnson was wounded on the first day of the Battle of the Somme. His torn and bloodstained tunic serves as evidence of a bitter struggle that saw the British Army suffer nearly 60,000 casualties on the worst day in its history.

The Big Push

In 1916 the Allies developed a new plan. A ‘Big Push’ on the Western Front would coincide with attacks by Russia and Italy elsewhere.

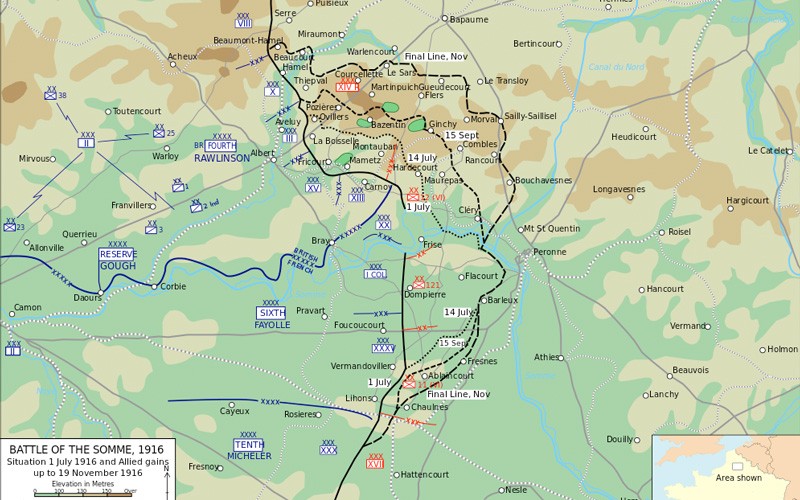

The British wanted to attack in Belgium, but the French demanded an operation at the point in the Allied line where the two armies met. This was on the River Somme in northern France. The attack was planned for August along a 25-mile (40km) front.

On 21 February 1916, aiming to ‘bleed France white’, the Germans attacked Verdun. To assist the French, the Somme offensive was launched earlier than planned with the inexperienced ‘New Armies’ providing the bulk of the British troops involved.

General Sir Douglas Haig’s plan was that, while Lieutenant-General Sir Edmund Allenby’s British Third Army made a diversionary attack in the north and the French Sixth Army attacked in the south, Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Rawlinson’s Fourth British Army would break through in the centre. Lieutenant-General Hubert Gough’s Reserve Army, including cavalry, would then exploit this gap and roll up the German line.

Although Haig was confident that a breakthrough was possible, the more cautious Rawlinson favoured a step-by-step approach, targeting limited gains to wear the Germans down. These differing views would lead to British confusion in deciding on objectives and how to exploit any success.

Bombardment

On 24 June 1916 a seven-day preliminary bombardment began. Haig’s artillery was expected to smash German defences and guns, and destroy the barbed wire in front of the enemy lines. When the attack began, it would provide a creeping barrage behind which the infantry could advance.

The British believed that the Germans would be so shattered by this bombardment that the infantry would simply walk over and occupy their trenches. But they had overestimated the power of their artillery.

Their guns were too thinly spread for the task in hand. And although they fired 1.5 million shells, two-thirds of them were shrapnel. These threw out steel balls when they exploded – devastating against troops in the open, but largely ineffective against concrete dugouts and the men sheltering within them. Furthermore, it has been estimated that as much as 30 per cent of the shells failed to explode.

As a result the German defences were not destroyed and in many places the wire remained intact.

1 July 1916

Following the detonation of several huge mines dug beneath the German lines, 14 British divisions attacked at 7.30am on 1 July 1916.

In most cases they were unable to keep up with the barrage that was supposed to take them through to the German trenches. This gave the Germans time, once the barrage had lifted, to scramble out of their dugouts, man their trenches and open fire.

Haig’s infantry were met by a storm of machine-gun, rifle and artillery fire. They suffered over 57,000 men killed or wounded during the day.

Middlesex decimated

2nd Battalion The Duke of Cambridge’s Own (Middlesex Regiment) suffered particularly sweeping losses during 8th Division’s attack at Mash Valley near Ovillers-La Boisselle.

It advanced in four waves but machine-gun fire devastated its ranks. Just 51 of 673 officers and men made it to the end of that first day unharmed. The rest were either killed, wounded or reported missing. Only one officer out of the 23 who led the attack remained unwounded.

‘As soon as our leading wave left our trenches to assist it was caught by heavy machine gun fire and suffered heavy losses. As soon as the succeeding waves came under this fire they doubled forward and before anyone reached the German front line the original wave formation had ceased to exist.’

Among the wounded was Temporary Captain George Johnson, one of the few men to actually reach the second line of German trenches. They managed to hang on there for a while awaiting reinforcement, but once their ammunition ran out they were forced to retire to shell holes in front of the German lines before returning to British trenches under cover of darkness.

During the fighting Johnson was hit in his chest, pelvis and arm. The sleeve of his uniform had to be cut away so that medics could attend to his injuries.

Attacks continue

Despite the French making good progress in the south, and some local successes, in most places the attack was a bloody failure. But, with the French still under pressure at Verdun, there was no question of calling off the offensive. More attacks were mounted between 3 and 13 July, and a further 25,000 men were lost.

Gradually, the British tactics improved. On 14 July four British divisions made a dawn attack on Bazentin Ridge. Supported by a very short but intense artillery bombardment, they caught the Germans by surprise and by mid-morning they had captured the ridge.

Attacks continued on the Somme throughout the summer, mostly on a series of individual objectives, with the Germans frequently mounting fierce counter-attacks. The ‘Big Push’ became a slow, grinding struggle of attrition.

Biography

George Johnson (1878-1968) was born in Fulham, London, on 2 February 1878, the son of James Johnson and Catherine Johnson née Dowd. His father was a bricklayer and he had three brothers and four sisters. The family lived at 5 Fane Street, Fulham.

Educated at Fulham Board School, George enlisted in The Duke of Cambridge’s Own (Middlesex Regiment) at Hammersmith on 2 November 1896 aged 18 years and four months. He gave his trade as labourer and had already been serving with the Royal East Middlesex Militia since June the previous year. Johnson was promoted to lance-corporal in April 1898 and corporal in February 1899.

George was married to Edith Jane Mabel Gunter of Woolwich in June 1899. The couple had four children, Edith Catherine, Sydney James, Victoria May and Ivy Maude. All were born in military establishments at Hounslow, Mill Hill, Aldershot and Singapore.

Johnson served with the 2nd Battalion of the Middlesex in the Boer War (1899-1902) from December 1899 until August 1900 when he transferred to the newly-raised 4th Battalion at Woolwich. For his South African service he received the Queen’s South Africa Medal with six clasps. (You can see the medal ribbon on his tunic.) Johnson was promoted to sergeant in April 1901.

In 1903, on the termination of his initial engagement, he extended his service to complete 12 years with the colours. Postings to India and Singapore with the 3rd Battalion followed. He extended his service again in 1908 and was promoted to colour sergeant in December of that year. Johnson was appointed quarter master sergeant in July 1913.

He was stationed in India on the outbreak of the First World War, but returned to England in December 1914. After over 18 years in the ranks George was commissioned as a second lieutenant in January 1915 and posted to the 5th (Reserve) Battalion at Rochester. He proceeded to France in February and re-joined the 2nd Battalion in April. This formation had landed at Le Havre in November 1914 and was attached to 23rd Brigade in the 8th Division. In September 1915 Johnson was made a lieutenant.

The 2nd Battalion moved with its division from Flanders to the Somme front in March 1916 and spent several months there training and manning the trenches in the lead up to the battle. Johnson was promoted to temporary captain in June 1916.

George was evacuated home after being wounded. Embarking on 3 July 1916, he was sent to St Thomas’ Hospital in London. A lengthy period of rehabilitation followed and in 1917 he was eventually passed for light duties at the regimental depot at Hounslow and then with the 5th Battalion at Chatham.

However, the wound to his pelvis continued to plague him. He returned to hospital several times, undergoing operations to remove bone and bullet fragments at Queen Alexandra’s Military Hospital. In July 1917 he was granted a war wound pension.

In November 1917 George was appointed a clerical officer with the Ministry of Pensions in Chelsea, but remained in the Army. At this time he was living at 81 Peterborough Road in Fulham. He was finally discharged on health grounds on 29 April 1921 with the rank of captain, but retained his post at the ministry as a civilian.

Johnson retired from this in July 1944. He was then living at 37 Central Road, Sudbury, Middlesex. He died in 1968.

Explore further

- Article: Other Soldier Stories

Explore the map for similar stories

Captain George Johnson - Fulham, County of London

First World War in Focus

First World War in Focus