Brigadier-General Hubert Rees, CMG, DSO, c1918

Published in The History of The Welch Regiment (vol 2 1914-18) by Major-General Sir Thomas O Marden, 1932

Hubert Rees vividly describes his role in one of the key battles of the opening months of the war, when serving as a captain in 2nd Battalion The Welsh Regiment.

Race to the Sea

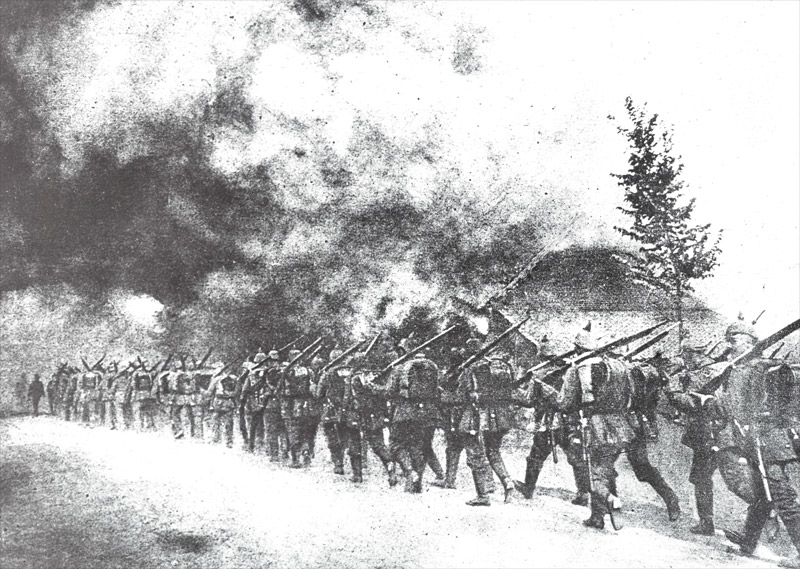

Following their defeat on the Marne in early September 1914, the Germans had pulled back across the Aisne and dug in on the high ground of the Chemin des Dames ridge on the north bank of the river. Allied attempts to dislodge them were unsuccessful, so they attempted to outflank the Germans to the north.

This set in motion a period of fighting from late September to the end of November 1914 that is often called the ‘Race to the Sea’. Both sides attempted to outflank each other, gradually moving northwards towards the French-Belgian coast.

In October 1914 the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), now reinforced with fresh units, was switched from the Aisne in France to Ypres in Belgium. From 20 October to 22 November it helped to defeat a major German attempt to break through and reach the Channel ports. This Allied victory at the First Battle of Ypres ended the ‘Race to the Sea’.

Annihilation at Gheluvelt

One of the key engagements during the Ypres fighting was the Battle of Gheluvelt (29-31 October 1914). Here, according to a first-hand account by Hubert Rees, ‘the 2nd Battalion of the Welsh Regiment was annihilated’ during a massed German assault.

Rees, a captain at the time, continues:

‘As soon as it became light, the storm broke. The trenches, lane, and village were deluged with shells of all calibres. It was impossible to move in the sunk lane and many men were hit. After the bombardment had been going on for some time, a few wounded men from B Company came in to say Marshall had been killed and that practically the whole company destroyed. The lane itself was indefensible, so Colonel Morland decided to move back to the front of the village and hold that with what men he could collect.

‘Young had come in from my two platoons on the left badly wounded by a rifle bullet. I crawled down to the end of the sunk lane to see if I could get back any of his men, who were in a hopeless situation. When I got to the end, I had a good view of their trench 50 yards off. There was a partially dug communication trench, only a couple of feet deep, between the end of the lane and them. A number of men were trying to run across this 50 yards to the lane, instead of crawling up the trench. I shouted at them to try the trench, but could not be heard. About 25 men attempted to run, but not a single man got more than half way and they seemed to me to be killed outright. It was useless waiting so I went back up the ditch alongside the Menin Road, following the men the colonel had already withdrawn.

‘I found my only remaining platoon more or less intact at the barricade and that Morland had moved towards the SWB [South Wales Borderers]. I started moving the platoon to follow Morland. The shell fire around the barricade was very violent. Two burst in the house behind which I sheltered, one cut the sign post neatly in half at the corner, another came through a wall 10 yards away and killed a man who was passing. Eventually I got away with a dozen men, four of whom were carrying Young in a mackintosh sheet, and one man had a machine gun of which the tripod had been blown to pieces and for which he had no ammunition. I followed Morland, who I estimate had about 80 men with him.

‘I saw no signs of them where I expected to find them and concluded that they had been forced by the hail of shells to move farther back. Several of my dozen men had been wounded by shrapnel, so without seeing anyone at all, I went through the northern outskirts of Gheluvelt and finally arrived at the position of 54th Battery, RFA [Royal Field Artillery]; commanded by Major Peel to whom I reported that I did not think that were more than 100 men of the Welsh Regiment left. He obviously disbelieved me, and I fancy seriously thought putting me under arrest for spreading alarmist reports. I confess to being shaken, the stock of my rifle had been shot through and the strap of my water bottle cut. He directed me to stand by as escort to the guns. I remained with the guns for some time, collecting stragglers until I had 40-50 men.

‘At midday a battalion advanced from our left rear moving in lines of companies under heavy accurate shrapnel fire. These turned out to be the Worcesters. About the same time, Lyttleton came over from the brigade to say that every available man was to counter-attack. I followed the Worcesters and came up to their reserve company in a trench to the left rear of Gheluvelt. The rest of the battalion had disappeared on the flank of the village and the rifle fire was heavy. I pushed on across a valley which ran up beyond the trench, through a confused disorganised mass of men under heavy shell fire, and lost most of my scratch command in the confusion.

‘I went on to see what was going on and just reached the end of the village when I heard my name shouted and, turning back, I saw Colonel Morland. He shouted to me to come to him saying that these 10 men attacks were no use. He added that Ferrar had been killed leading a bayonet charge near the barricade and that the battalion had been wiped out. It appeared that while I was absent with the 54th Battery, the survivors under Colonel Morland, Major Pritchard, Captain Ferrar and Moore had had a most desperate fight on the north edge of Gheluvelt, at one time getting as far back as the barricade where Ferrar was killed and Pritchard severely wounded. Morland and I started to walk back towards the 54th Battery and men from all the regiments involved were running back in the same direction. We endeavoured to rally a few of the groups and collected 25 men of the Welsh Regiment by the time we reached the guns. We got into a trench near the battery and were joined by Moore and Corder.

‘By this time, the enemy had pushed up south of the Menin Road past Gheluvelt as the battery was under rifle fire and bullets were striking the parapet of a trench a little to our right. Captain Robinson came over to say that Major Peel had been wounded by a bullet through the leg and that he was now commanding the battery. There were now eight officers standing together in the trench. Moore on the left, myself next, then Morland and next to him Captain Robinson with Corder, a captain in the Gloucesters, and somebody else beyond again. It was then that a shell burst in front killing Moore on my left and mortally wounding Colonel Morland on my right. It was a final blow. Morland was a terrible loss. He remained to the very end as cool and collected as if he was on parade at home. Moore was also a great loss and the regiment lost one of its bravest officers.

‘At this time, Corder and myself were the only two officers who had survived the fighting at Gheluvelt, and we had about 25 men. [Having taken command of the battalion] these I spread out as a firing line across a turnip field a little in front of the guns and went to interview Robinson. I suggested he should open fire on some houses about 500 yards away on the south side of the Menin Road which were obviously full of snipers. He blew the houses about pretty badly with HE [high explosive] and then continued with shrapnel on the slope beyond them. This put a stop to the rifle shooting, which was getting rather trying.

‘Lieutenant Blewitt of this battery came to say that the Germans appeared to be bringing up a field gun to the barricade in the middle of Gheluvelt and asked permission to take an 18-pounder on to the road and have a duel with it. Having got permission, he man-handled the gun on to the road. The German gun fired first and missed and Blewitt did not give him another chance. He put a stop to any trouble from that quarter for the rest of the afternoon.

‘If the Germans had pushed home their attack during the afternoon there was nothing to stop them. About 5pm I was handed command of the 1st Queens, which consisted of Lieutenant Lloyd and 21 men. Major Watson of the Queens, who put me in command, went off to act as brigade major of the 3rd Brigade. My force, consisting of these two battalions, only totalled some 60 men and two officers, the combined strengths of the two that morning could hardly have been less than 1,200 men.

‘I set out to discover our exact situation. I was at a farm house about 400 yards from the Menin Road. Between me and the road there was a remnant of the Royal Munster Fusiliers and 200 yards of trench full of men who belonged to every regiment of the Army. They were without officers and fast asleep from exhaustion. About that time, two fairly strong companies of the Berkshires came through with their right on the Menin Road. I spoke to their CO [commanding officer] and suggested some caution, he said he had been told to go straight ahead and did so until stopped by rifle fire a little further on.

‘I next went to the left and found the 1st Division Cyclists, 160 strong, holding a front of 400 yards with the Black Watch on their left on Polygon Wood. I then went to Gheluvelt Chateau, where I found the SWBs under Lieutenant Colonel Leach still in possession, having had some desperate hand to hand fighting in the chateau grounds. I told Leach what the situation was and then returned. The SWBs withdrew and passed behind my farm shortly afterwards.

‘Lieutenant Hewitt, Sergeant Smedley and 5 men reported to me about 11pm. He said that they were the sole survivors of the two platoons with whom he had disappeared on the 29th. A shell had killed or wounded five men a few yards away as he was returning. He had been with the 7th Division holding some trenches in the direction of Kruisech. They had been heavily attacked but had beat off all attacks until, after dark, on the 30th, he found himself with 24 men completely cut off by the Germans, who had driven back the troops on either flank. He decided on a bold experiment and forming his men up in fours marched through the Germans in the dark without being detected. He attached himself to the 2nd Queens whom he found holding trenches at the edge of Veldhoek Woods. They came in for heavy shelling and having lost most of his men set out to find the battalion.

‘At 2am, on 1st November, I was ordered to move the Welsh and the Queens south of the Menin Road and dig in. The SWBs, who were still fairly strong, held about 400 yards southwards from the road and we extended beyond them. Colonel Leach, commanding, was badly wounded by a shell splinter in the foot, and Major Reddie became their commanding officer. We had already dug one lot of trenches that night and now had to dig another set before dawn, with only three hours to do it in.’

Rees’s battalion lost nearly 600 men during the fighting, with 16 officers killed, wounded or missing.

Although Gheluvelt was lost late on 31 October, the momentum of the German advance had been broken by a dashing counter-attack by 2nd Battalion The Worcestershire Regiment.

Images courtesy of Diana Stockford

Biography

Hubert Conway Rees (1882-1948) was born at the Vicarage in Conway, Carnarvonshire, the only son of Canon Henry Rees and Harriet Rees. Educated at Charterhouse, he joined the Army and went on to serve in South Africa during the Boer War (1899-1902).

Rees married Katharine Adelaide Loring in 1914. They had one daughter, Mary Katherine.

When war was declared in August 1914, he was a company commander with 2nd Battalion The Welsh Regiment with whom he fought in the Retreat from Mons, on the Marne and the Aisne before being moved to the Ypres sector. Soon after, at Langemarck on 23 October 1914, Rees was awarded the Distinguished Service Order for his efforts in helping repel several German attacks.

In January 1915 Rees relinquished command of 2nd Battalion and returned to Britain. He joined the staff of 43rd Division, which moved to France in November. The following June he was given temporary command of 94th Brigade in place of Brigadier-General Carter-Campbell who was on sick leave. He led this formation in the unsuccessful attack at Serre on 1 July 1916. On Campbell-Carter’s return from leave he was given command of 11th Brigade, which he led during the subsequent Somme battles.

After a brief period at home in command of 13th Reserve Brigade, Rees returned to France in March 1917 to take command of 149th Brigade, seeing action at Arras the following month.

In July 1917 he was taken ill and hospitalised, not returning to the Western Front until February 1918 when he was made commander of 150th Brigade. He led this formation with distinction during the German Spring Offensive and was eventually captured in May.

Interviewed by the German Emperor, Kaiser Wilhelm II, on 28 May 1918, Brigadier-General Rees was held in several prisoner-of-war camps before returning to Britain in December 1918.

He retired from the Army in 1922, and died on 3 January 1948 at Kyrewood House, Tenbury Wells, Worcestershire.

Explore

- Article: Other Soldier Stories

Explore the map for similar stories

Captain Hubert Rees - Conway, Carnarvonshire

First World War in Focus

First World War in Focus