Siegfried Sassoon painted by Glyn Warren Philpot, 1917

© The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, UK (CC BY-NC-ND)

The poet Captain Siegfried Sassoon’s controversial ‘Soldier’s Declaration’ was written on 15 June 1917, and published a month later in ‘The Times’. His service notebooks, which have recently been digitised by the National Army Museum, show that Sassoon was at first a typical officer who was actually in favour of the war.

Early life

Siegfried Sassoon (1886-1967) was born on 8 September 1886, in Matfield Kent. Although his name suggests otherwise, he actually had no German heritage. His father, Alfred Ezra Sassoon, was the disinherited son of a line of wealthy Baghdadi Jewish bankers. His mother, Theresa Thornycroft, was from a Catholic family of well-known sculptors.

Sassoon was the middle child of three boys. He grew up with his brothers, Michael and Hamo, in the family’s large house known as ‘Weirleigh’ in Kent. He was educated at New Beacon School in Kent and later at Marlborough College in Wiltshire.

In 1905 Sassoon earned a place at Clare College, Cambridge, to read law. The experience was to be a resounding academic failure, but it gave Sassoon the opportunity to nurture his love of poetry and literature. He would often prefer to write blank-verse poetry about Joan-of-Arc, than bother with his studies. After attempting to read history instead, he eventually pulled out of university completely in 1907.

Sassoon returned to Weirleigh and spent the next eight years as a country gentleman, writing poetry, hunting and dabbling with a career as a professional sportsman. His poetry made little impact during this time, but he was able to mix with many of the bohemian creatives of the day including the poet Rupert Brooke.

War service

Sassoon volunteered for the Sussex Yeomanry just before the war, and was in service with them as a trooper by August 1914. Following a riding injury in October 1914 he was sent to officer training. He was granted a commission as a second lieutenant in the Royal Welch Fusiliers on 29 May 1915. His injury meant that he missed the Gallipoli campaign, in which his brother Hamo and fellow war poet Rupert Brooke lost their lives.

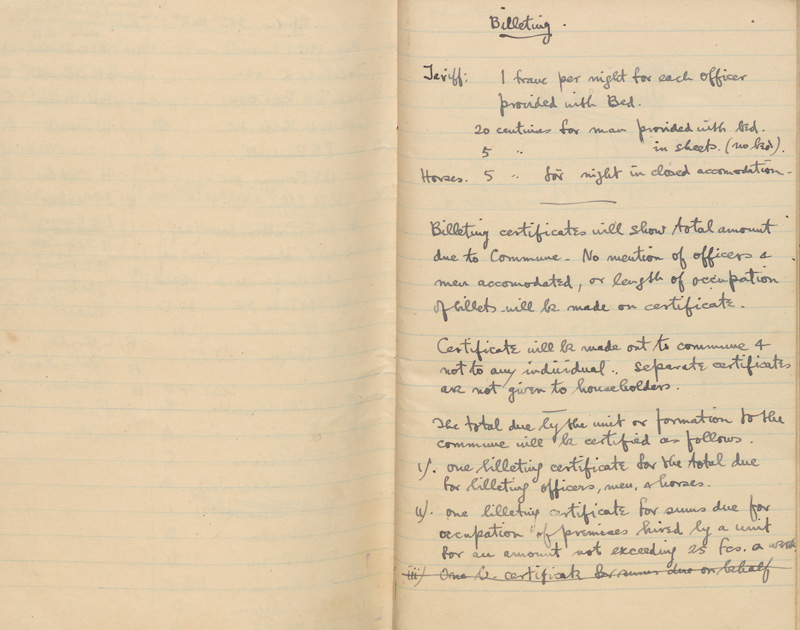

Sassoon’s notebook containing veterinary notes on how to care for horses, from January 1916

NAM. 1995-08-11-1

He arrived in France in November 1915, where he met Robert Graves, a fellow officer and writer. The two began a long-lasting friendship through their shared love of poetry.

Sassoon initially worked as a transport officer, supplying communication trenches. The job was dangerous, as these lines were as much a target for enemy shellfire as the front line. But he felt disenchanted by his role and was keen to be part of the action.

Towards the end of March 1916, he was finally granted a front-line position, and quickly became known as ‘Mad Jack’ by his men, for his recklessly brave exploits. He was awarded the Military Cross for bringing back a wounded lance-corporal under heavy fire in May 1916 and was even recommended for the Victoria Cross for capturing a German trench single-handed.

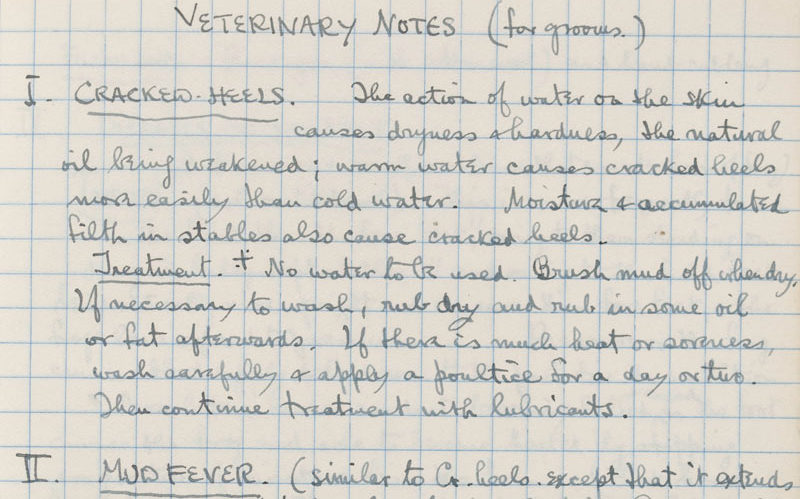

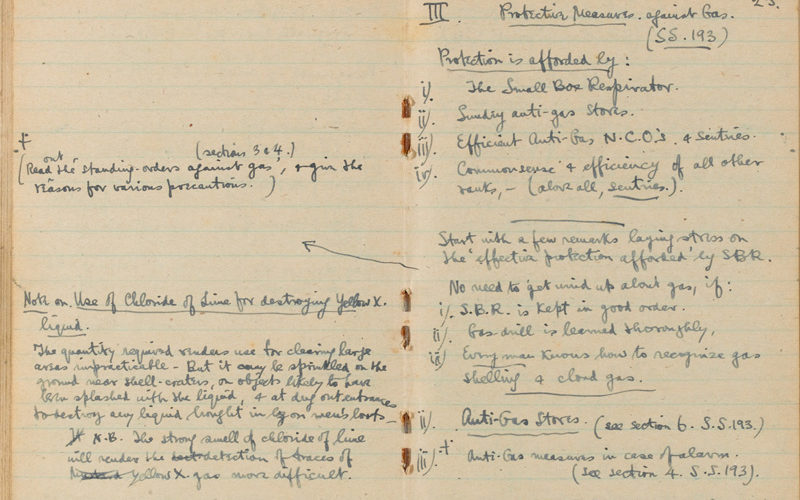

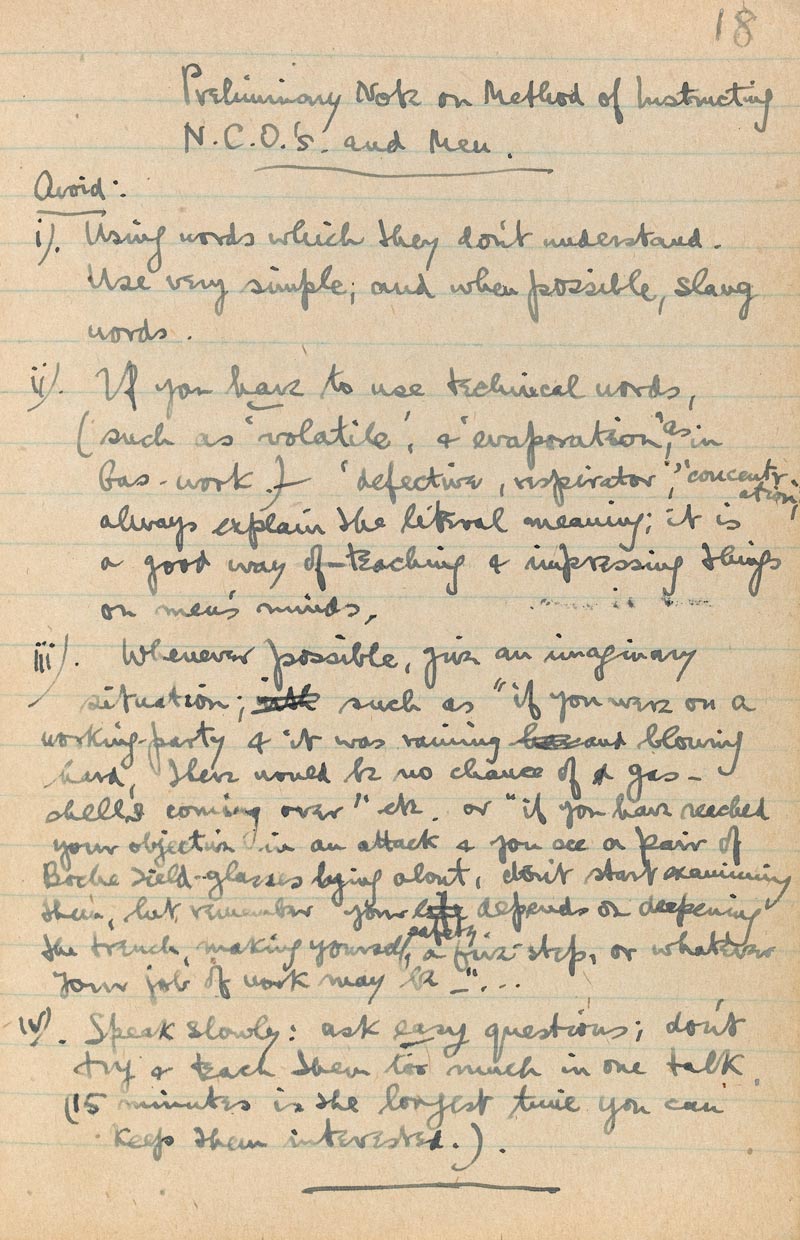

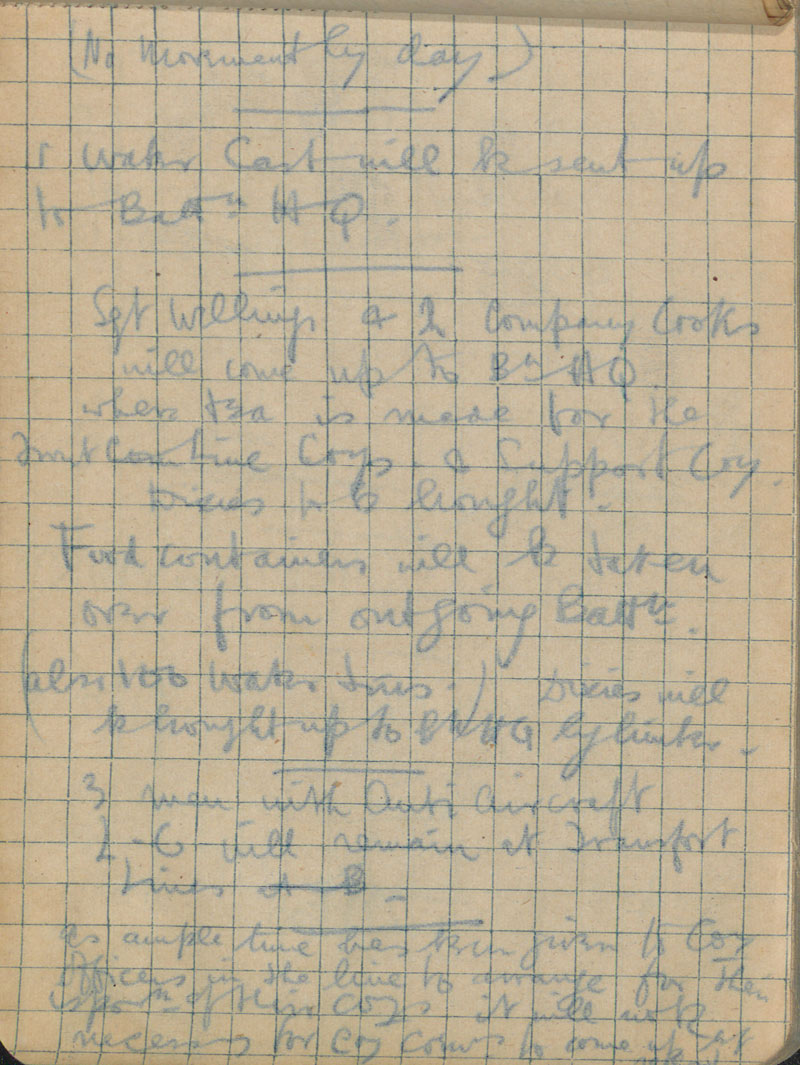

Sassoon’s notebook containing notes on attacking trenches, bombing, gas and tactics, c1916

More details: NAM. 1995-08-11-6

Sassoon was wounded taking part in the Somme Offensive in the summer of 1916. While recovering, he had the opportunity to reflect on his experiences and the loss of his beloved friend David Thomas who had died on 18 March 1916. Sassoon found himself altogether less enthusiastic to return to the front than he had been a year earlier.

On his return to France in Spring 1917, Sassoon’s brave exploits became suicidal. He was wounded again on 14 April 1917, during the Battle of Arras, after intentionally sticking his head above the parapet to make himself an easy target for German snipers. The night before he had written in his diary: ‘Fully expecting to get killed on Monday morning.’

A Soldier’s Declaration

During his recovery Sassoon’s anti-war feeling peaked. He resolved to express his anti-war feelings publicly.

On 7 June 1917, the day the offensive began at Messines Ridge, Sassoon sought the advice of a group of influential anti-war activists on what to do. In London, he met with HW Massingham, editor of ‘The Nation’, who introduced Sassoon to the writer John Middleton Murry and the philosopher Bertrand Russell. They felt that a public statement by a decorated officer could have a powerful impact for the anti-war movement.

Sassoon agreed, and spent the next two weeks working on his statement. He completed his piece, titled ‘A Soldier’s Declaration’, on 15 June:

‘I am making this statement as an act of wilful defiance of military authority, because I believe that the War is being deliberately prolonged by those who have the power to end it. I am a soldier, convinced that I am acting on behalf of soldiers. I believe this War, upon which I entered as a war of defence and liberation, has now become a war of aggression and conquest…

‘I have seen and endured the sufferings of the troops, and I can no longer be a party to prolonging those sufferings for ends which I believe to be evil and unjust.

‘I am not protesting against the military conduct of the War, but against the political errors and insincerities for which the fighting men are being sacrificed…’

Sassoon then led what he described as a ‘double life’ while waiting for the declaration to be published. He did not inform his closest friends and family of what he had done, and had even applied to be a cadet instructor in Cambridge as a ruse. He also determined that he would return to Weirleigh and deliberately overstay his leave.

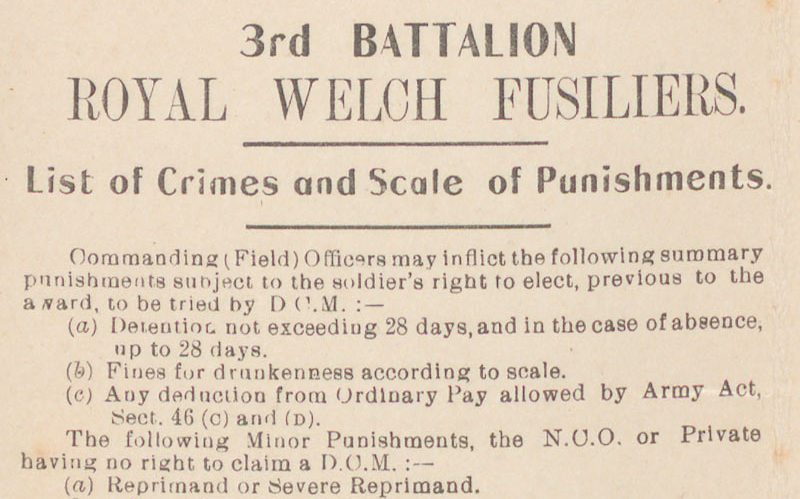

NAM. 1995-08-11-14

When Sassoon received a telegram from the adjutant of 3rd Battalion The Royal Welch Fusiliers on 4 July, he replied with a copy of ‘A Soldier’s Declaration’ and a letter, apologetically expressing his intention not to return and to make the statement public. He wrote that he was ‘fully aware of what I am letting myself in for’ and hoped to receive a court-martial.

But things did not progress as planned. The army recognised that putting a celebrated soldier up against a military tribunal would cause a public scandal, and instead summoned Sassoon for an examination by the Medical Board.

In frustration, Sassoon threw the ribbon from his Military Cross into the River Mersey, and refused to attend. But his friend Robert Graves, who shared his anti-war feelings, wrote to him saying that his trial would never receive the publicity he desired and persistent refusals would see Sassoon locked up in a lunatic asylum. Sassoon relented, and attended the examination.

‘A Soldier’s Declaration’ was read out in Parliament and published in ‘The Times’ on 31 July 1917, the same day that the British began the Battle of Passchendaele.

Conscientious objection

Sassoon was not alone in expressing his anti-war sentiments. There were around 16,000 recorded men who also refused to fight during the First World War. These men were known as conscientious objectors because, unlike those unfit for service, they refused to serve for reasons of conscience such as religion or freedom of thought.

Not all these men were politically opposed to the war. Many were Quakers and traditionally pacifist, while some were already employed in reserved occupations, like farming or forestry, which were essential to the war effort.

But, as Sassoon himself found, being a conscientious objector was for some as difficult as life on the front line. There was a huge public backlash towards objectors, who were widely seen as unpatriotic, degenerate cowards, either too scared or too lazy to sacrifice themselves for their country. Even Sassoon’s mother believed that those opposed to the war were ‘mad with their own self-importance’.

NAM. 2014-01-7-1

In 1914 the Order of the White Feather tried to shame men not in uniform into signing up by branding them cowards. They gave them a white feather, the traditional symbol of cowardice.

After the introduction of the Military Service Act in March 1916, objectors had to persuade a Military Tribunal of the grounds for their objection. In a reflection of public opinion, such tribunals were notoriously harsh on objectors. Around 6,000 men who could not provide a legitimate reason for their objection were forced into the army, with some even being court-martialled and sent to prison if they further refused to obey orders.

Later life and legacy

On 24 July 1917 Sassoon was declared unfit for service and referred to Craiglockhart War Hospital near Edinburgh, an institution for shell-shock sufferers. There he met the poet Wilfred Owen, and helped nurture his poetry writing.

But the longer he stayed, the more he felt guilty about leaving his men. By the end of October, Sassoon was writing to Graves to express his desire to return to the war, even though his feelings expressed in ‘A Soldier’s Declaration’ had not changed.

After proving that he was once again fit for military service in November, Sassoon returned to the front, first in Palestine and then France, where he was wounded for a third time in July 1918. During this time, he succeeded in publishing two volumes of war poetry.

Sassoon had long feared that his war service could cut short his poetry career, worrying that he might be killed before any of his poems were published, but this was not to be the case.

After the war, Sassoon continued to write. He worked first as literary editor for the socialist newspaper ‘The Daily Herald’, and then on his acclaimed fictionalised trilogy of autobiographies, ‘Memoirs of a Fox Hunting Man’, ‘Memoirs of an Infantry Officer’ and ‘Sherston’s Progress’ which all explored the life of George Sherston, an avatar of Sassoon himself.

Sassoon had realised his homosexuality at university. He enjoyed a series of post-war affairs with high profile figures including the actor Ivor Novello and ‘Bright Young Thing’ Stephen Tennant. However, in 1933 he married Hester Gatty, with whom he realised his dream of having a child. His son George Sassoon became a notable scientist and linguist.

By the end of the Second World War (1939-45) Sassoon’s marriage had broken down and he and Hester separated. Sassoon moved to Heytesbury in Wiltshire where he lived in seclusion for the rest of his life, but maintained a close circle of friends. He was made a Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 1951.

Sassoon died of stomach cancer on 1 September 1967, aged 80. He was buried at St Andrew’s Church in Mells, Somerset. On 11 November 1985 he was commemorated as one of 16 Great War poets at Westminster Abbey, alongside Rupert Brooke, and his friends Robert Graves and Wilfred Owen.

Explore further

- Article: Other Soldier Stories

- Video: The Story of Conscription

- Interactive Video: Do You Enlist?

Explore the map for similar stories

Captain Siegfried Sassoon - Matfield, Kent

First World War in Focus

First World War in Focus