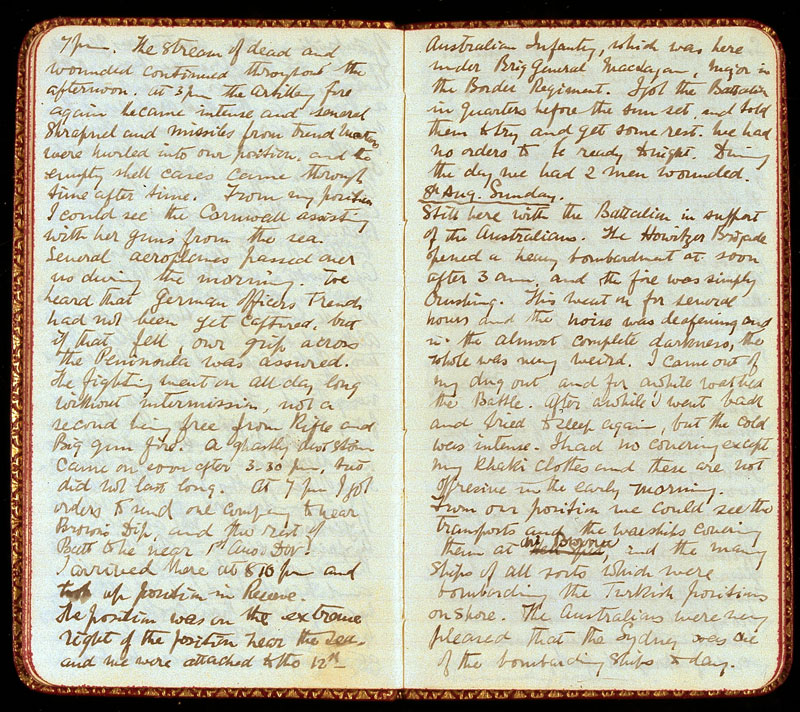

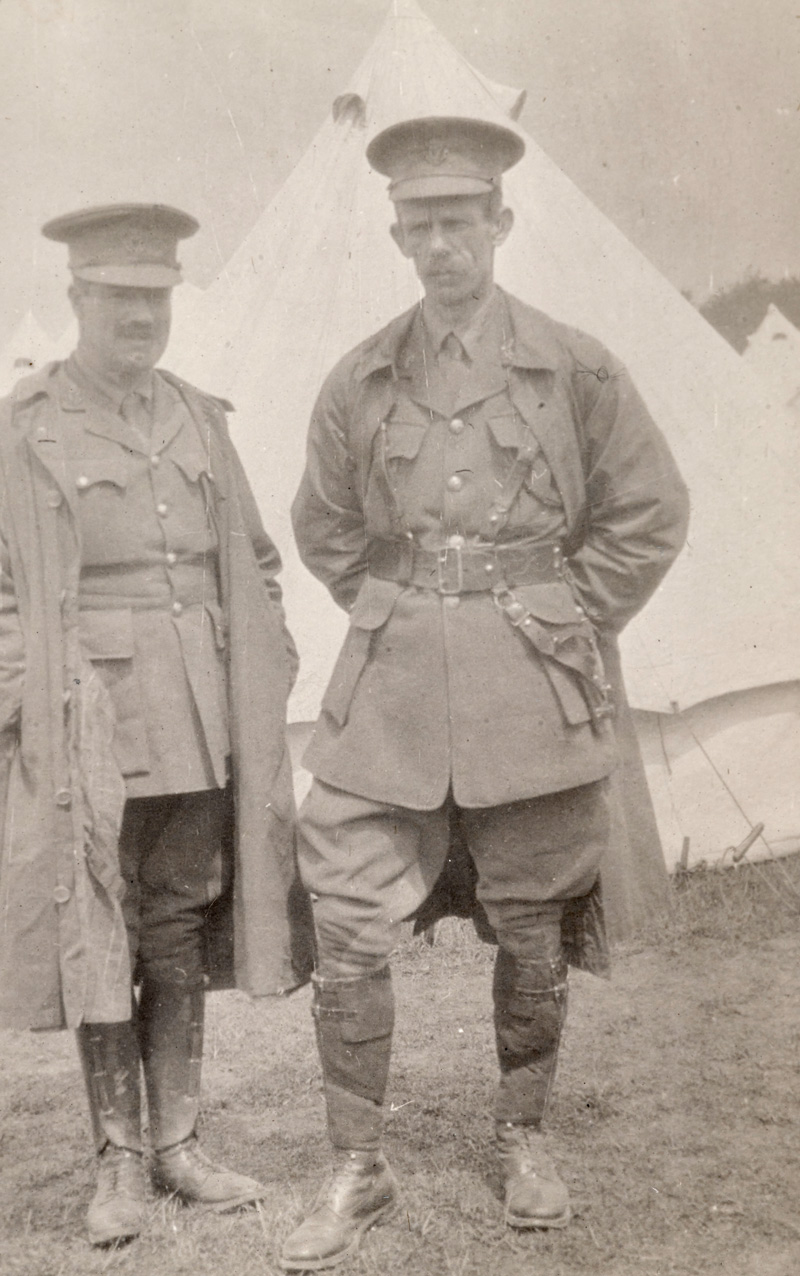

Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Jourdain, 5th Battalion The Connaught Rangers, 1915

More details: NAM. 1963-12-307-50

The diary entries of Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Jourdain, 5th Battalion The Connaught Rangers, describe the landings at Anzac Cove in August 1915 and the failed Allied attempts to break out from the Gallipoli beaches.

Gallipoli campaign

The ongoing deadlock on the Western Front led the Allies to formulate plans to attack Turkey, an ally of the Central Powers. If the Turkish capital of Constantinople (now Istanbul) was attacked, via the Dardanelles Straits, it might relieve the pressure on Britain’s ally Russia. It could also open a supply route to Russia through the Black Sea and at best knock Turkey out of the war altogether.

Plans were made for a naval expedition to seize the Dardanelles in February and March 1915. Given their strategic importance, the straits were well defended by minefields and fortifications. There were also many Turkish gun emplacements on the Gallipoli Peninsula to the north and the Asian coast to the south.

When the naval attacks failed to destroy these defences, it became clear that troops would have to seize the peninsula and destroy the guns and minefields. Only then could the Royal Navy force the straits and push on to Constantinople.

Allied troop landings began on 25 April 1915. British, Indian and French soldiers fought alongside men from Australia and New Zealand, the ‘Anzacs’, whose exploits became a legend in their home countries.

Heavy casualties were incurred, but two beachheads were established by General Sir Ian Hamilton’s force. They were at Cape Helles, on Gallipoli’s southernmost tip, and further up the coast near Gaba Tepe (later renamed Anzac Cove).

Hamilton was determined to extend the Allied position in the south, with attacks directed from Helles towards Krithia and the nearby hill of Achi Baba. The troops would then link up with the soldiers at Anzac Cove.

Once Krithia was in Allied hands Hamilton intended to continue to push northwards, removing Turkish defenders from the heights defending the straits. Three successive operations were launched upon Krithia between 28 April and 4 June 1915. All failed to break the Turkish defences and the campaign stalled.

August offensive

During the nights of 3-6 August 1915, around 20,000 soldiers were brought ashore at Anzac Cove in Gallipoli for a new offensive. Among them were 5th (Service) Battalion The Connaught Rangers, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Jourdain.

In his diary Jourdain described the journey ashore and the march inland:

‘After a quiet voyage we reached the coast of the Gallipoli Peninsula, and noticed that heavy gun fire was going on at the point Sed-al-Bahr. We could see the flashes plainly and the explosion of the shells could be easily seen. At 10.20pm we came up outside Anzac Cove and anchored… at 3am lighters came alongside. Then it was a race to get to land…The Leinsters had one shot in the chest, and the Hampshires one in the stomach. We had one wounded in the hand and one slightly in the shoulder by shrapnel…

‘On landing we were ordered to follow a guide and advance at once towards the connecting trench. The rifle fire was very heavy and the enemy began to shell us with shrapnel, but the companies came up well and stood fire very well indeed… The firing became very heavy during the morning, and what with the shrapnel, machine guns and other shells it was quite impossible to sleep…At 11.15am a large shell hit a dug out and killed a man, Hall of C Company, blowing him to pieces. A while later QMS Galbraith and another man were wounded in the face by shrapnel…

‘[Later during a visit to Brigade HQ] the whole donga where we were was filled with shrapnel… When I went back to my lines I was pursued by dozens of bullets which were most plentiful… the firing never ceased for one moment.’

The new troops sent in August were intended to reinvigorate a campaign that had been bogged down for months. Hamilton launched his new offensive on 6 August 1915. It took the form of a diversionary action at Helles, a drive from Anzac Cove towards Sari Bair and a landing of new divisions at Suvla Bay. This latter force was to link up with the troops at Anzac and then advance across the peninsula.

The 5th Connaughts went into action on 7 August at Anzac in support of the Australians at Lone Pine:

‘At 4am the guns opened the bombardment and the trenches all round opened independent fire. The noise was deafening and the effect was simply awful. For a full half hour [the] terrific bombardment went on, and then the Colonials advanced to the attack. They took the plateau with great gallantry… Several hospital ships came in this morning and wounded after wounded man was taken down towards the landing stage at Anzac…

‘The attack has been in progress since early on the 6th and shows no signs of subsiding. The Australians [are] admired by all, and have shown the most splendid dash and courage [but] the stream of dead and wounded continued throughout the afternoon… From my position I could see the Cornwall assisting with her guns from the sea… The fighting went on all day, not a second being free from rifle and big gun fire…

‘Some of the Indian Mule Corps passing down with shells and rations came to the notice of the people on Gaba Tepe, who evidently signaled to a gun and shot after shot of shrapnel burst near the train killing and wounded several of the mules and their native drivers.’

Jourdain’s men later joined another drive from Anzac, advancing up the ‘terrible hill’ of Chunuk Bair on 10 August towards an area known as ‘the Farm’. The ‘leading platoons suffered heavily from snipers’ but eventually reached their goal. Here they found many wounded from the previous day’s fighting and set about evacuating them down to the coast.

After establishing a defensive perimeter they were reinforced, but a new advance ‘was beyond their power and after several losses they were driven back’. The Connaughts dug in and held a section of trenches for the next few days, ‘all the while under fire and suffering from a shortage of water’:

[Conditions were] terrible, wounded and dying men lying all over the place. Men groaning and dying without a murmur. I assisted as many as possible but it was horrible to contemplate.’

Although the landing at Suvla had caught the Turks by surprise, progress inland was too slow and the Turks were able to occupy the heights overlooking their position. The wider offensive also rapidly lost momentum by 10 August due to tough Turkish resistance and indecisive command.

Anzac breakout

In late August 1915 another attempt was made to break out of Suvla and link up with Anzac during the Battles of Scimitar Hill and Hill 60. During this period the 5th Connaughts supported the New Zealanders and Australians in the attack on Hill 60, which was launched from Anzac.

On 21 August, after a 70-minute bombardment, the Connaughts bayonet-charged the Turkish trenches with ‘rare dash’ while under machine-gun fire. The two foremost trenches were quickly taken and they pushed on up a sunken road towards the top of the hill. Their attack was halted by heavy shell and machine-gun fire.

Jourdain decided to consolidate the battalion’s gains around the lower parts of the hill to resist the inevitable counter-attacks. ‘The Turks came quite close and asked us to surrender… crying “Allah Allah” in shrill voices.’ The attacks were beaten off in conjunction with the New Zealanders. The Ottoman defenders, however, still managed to hold the heights. Further attempts to assault these positions failed.

The Connaughts were withdrawn on 22 August, their strength reduced to seven officers and 402 other ranks. They had lost three officers and 43 men killed, and nine officers and 148 men wounded. A further 47 men were reported missing.

Jourdain wrote:

‘I came through the gap where we had issued forth to the attack the previous day. My thoughts went back to the many brave fellows who had gone forth just over 24 hours ago and who would never return. All my staff had gone, and I was the sole survivor of the head quarters. It was very sad.’

The Hill 60 operation finally ended on 29 August. It was the last offensive action undertaken by the Allies at Anzac.

Conditions in the dug outs

Forced to dig in, the troops remained trapped around the three beachheads at Helles, Anzac Cove and Suvla Bay. Each of the beachheads was overlooked by high ground commanded by strong Turkish forces and was under constant artillery and sniper fire ‘from every quarter’. The latter was a constant threat:

‘About 7am one of our men who had foolishly stood on the skyline was shot through the head. He died at once… [Later] Father Leighton came and heard confession… bullets continually whistled overhead and before he had finished a man was brought down…shot through the head. It was in truth a dreadful thing to see men taken away so suddenly.’

The soldiers lived and fought in appalling conditions. Casualties from heat and disease overwhelmed the inadequate medical facilities. Jourdain recorded that the weather was ‘very hot and sultry and the dug out in which I was was very hot indeed [but at night] the cold was intense. I had no covering except my khaki clothes and these are not effective in the early morning.’ The men ‘lived on bully beef, jam and biscuits for weeks.’

Evacuation

At the end of September Jourdain’s battalion was withdrawn prior to transfer to the Macedonian front. In November it was decided to withdraw the entire Allied army. This was done with minimal losses by 9 January 1916.

Efforts had been made to deceive the watching Turks into believing that the movement of Allied soldiers did not constitute a withdrawal. The evacuation was the only successful operation during the whole campaign.

The Allies suffered over 252,000 casualties out of a force of nearly 500,000. The Turks sustained almost as many. From the Allied point of view the campaign had been a disaster.

Biography

Henry Francis Newdigate Jourdain (1872-1968) was born at Ashton-under-Lyne in Lancashire and baptised at Derwent, Derbyshire. He was the fourth son of ten children to Reverend Francis Jourdain, the vicar of Ashbourne in Derbyshire, and his wife Emily O’Farrell from Portumna in Galway.

Henry was educated at Queen Elizabeth Grammar School, Ashbourne, and at the Royal Military College Sandhurst. He was commissioned into The Connaught Rangers in February 1893, and promoted to lieutenant the following August.

Jourdain served throughout the Boer War (1899-1902). He saw action at Spion Kop, Ladysmith, Colenso and many other engagements.

By 1911 he was living at Palmyra Crescent, Galway. A keen golfer, he was also an enthusiastic hockey player and was appointed captain of the Galway Hockey Club that year. In April 1912 he was promoted to major.

Following the outbreak of the First World War, Jourdain raised the 5th (Service) Battalion of The Connaught Rangers on 19 August 1914 at the regimental depot in Galway. His new battalion was allocated to 29th Brigade in 10th (Irish) Division. After preliminary training in Ireland this formation moved to England in May 1915, concentrated in the Basingstoke area. In July it embarked at Plymouth for Gallipoli.

After Gallipoli, Jourdain and his battalion served in Salonika, Palestine and on the Western Front, including the Battle of Messines Ridge and the Third Battle of Ypres in 1917. Appointed a Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George for his services, he was given command of the 2nd Battalion and then served in Upper Silesia. He returned to Galway in early 1922 and married Molly O’Farrell soon after.

Following the disbandment of The Connaught Rangers in June 1922, Jourdain retired from the Army. He moved to Fyfield Lodge in Fyfield Road, Oxford, where his sister Miss E Jourdain, principal of St Hugh’s College, already lived. He was approached by Michael Collins to become Director of Training of the Irish Free State’s Army, but any possible involvement ended with Collins’s assassination in August 1922.

Throughout his life Jourdain was a noted medal collector and military historian. His book ‘Ranging Memories’ contains many reminiscences of his life in The Connaught Rangers and he contributed greatly to the regimental history, which was published in the 1920s. For many years he also edited their regimental journal ‘The Ranger’.

For his historical contributions he was awarded the Great Gold Medal of the Institut Historique de France in 1934 and was created a Chevalier of the French Order of the Academic Palms. He died in 1968 at the age of 96.

Explore

- Article: Other Soldier Stories

Explore the map for similar stories

Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Jourdain - Ashbourne, Derbyshire

First World War in Focus

First World War in Focus