In September 1917 Lieutenant Oliver Stewart of the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) achieved the status of ‘ace’ on the Western Front, winning the Military Cross for his actions. Stewart, who went on to become a test pilot and aviation journalist, wrote authoritatively about air combat as well as the social and emotional impact of modern war.

Air war

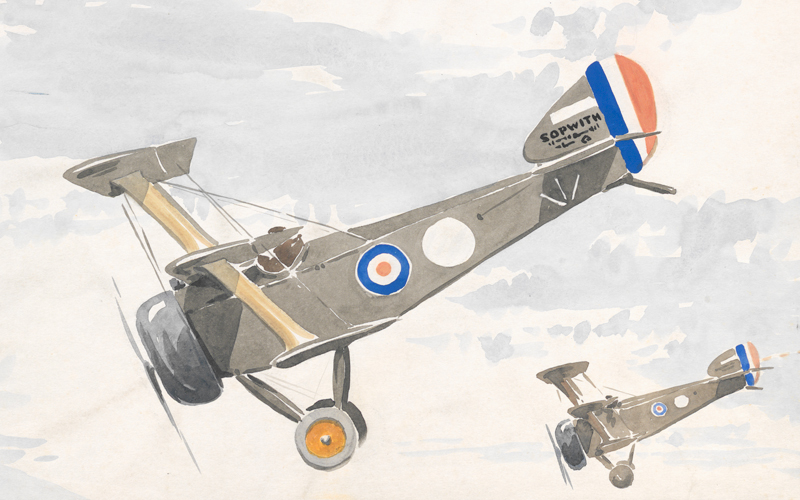

Stewart joined the air war in January 1917, flying photographic escort missions for 54 Squadron in a Sopwith Pup. At this time the struggle in the air was evolving. Machines were improving, tactics changing and the numbers of aircraft increasing.

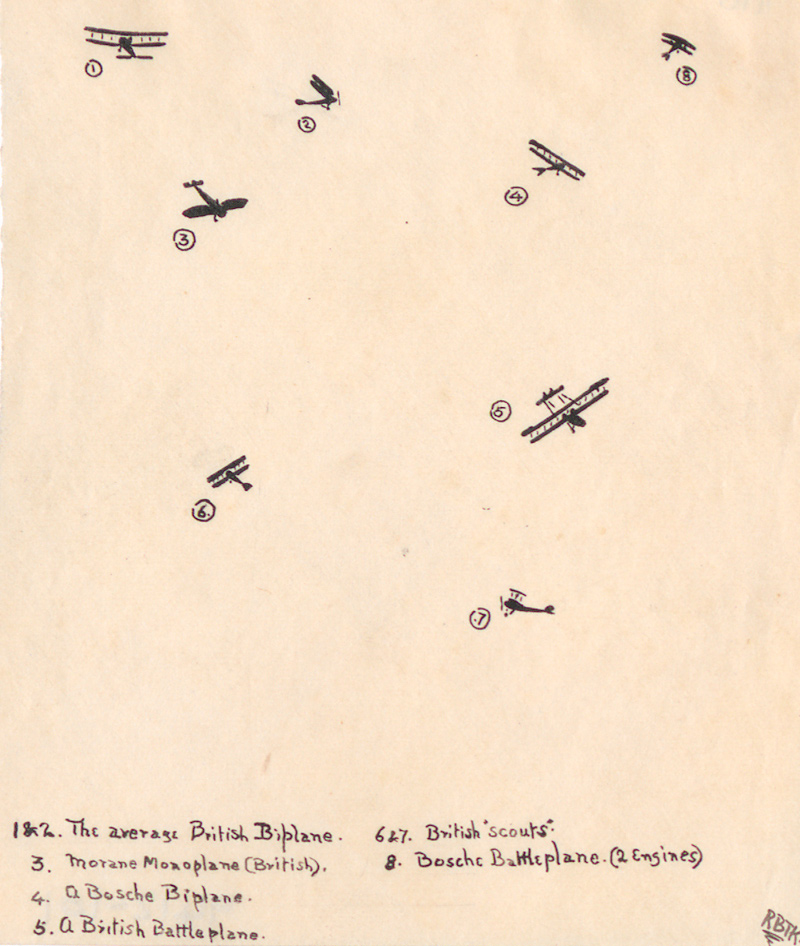

Reconnaissance and bomber aircraft were protected by successive waves of fighters operating at different heights. In turn, enemy aircraft, depending on their capabilities, attacked at different altitudes. Stewart describes how a formation was therefore ‘like a living cell under a microscope, the whole of the interior moving and squirming and writhing within it’.

Equipment

Open cockpits meant aircraft crew were equipped for cold weather, wearing sweaters, fur-lined boots, leather coats, helmets, gauntlets, goggles and face masks. Until the introduction of radios, communication between aircraft was limited to hand signals and wing-tip signalling.

Cold-blooded affair

Air combat was a truly cold-blooded affair. Victims were more often than not shot in the back at close range during fleeting but ferocious surprise attacks. With no parachutes, pilots caught in stricken aircraft had few options. Stewart’s advice for staying alive was relatively simple: stay high, avoid flying straight, watch the sun and the clouds for surprise attacks.

The popular image of pilots may have been one of gentlemen engaged in honourable combat, but Stewart believed ‘the devil, who tends to win battles more often, is on the side of the cunning battalions’. There was ‘nothing chivalrous or fine about air fighting. I had to learn to keep alive.’

‘Fighting in the air has a closer affinity to the back street brawl, the night club affray, the pub fight, than to the jousting of knights in armour.’

Stewart emphasised the importance of training and repetition. He wrote, ‘combat experience shows that things people do under stress or at high speed, are the outcome of habituation’. He also suggested natural aggression, particularly in reaction to attack, was present in the most successful pilots.

Sopwith Pup with airmen of 54 Squadron (Stewart on far right), 1917

More details: NAM. 1998-06-188-21

Stewart’s 54 Squadron increasingly flew offensive patrols and ground attack operations. At one point it was operating in the same sector as Manfred von Richtofen’s squadron, Jasta 11 – the infamous ‘Red Baron’s’ flying circus.

The Sopwith Pup, though loved by its pilots was soon outdated, its single fixed machine gun unable to compete with new German fighters like the Fokker Triplane which was equipped with twin Spandau machine guns. The SE5 and the Sopwith Camel and Triplane fighters would eventually help redress the balance in the air.

Aces high

Stewart survived ‘Bloody April’, a low point for the RFC, as superior German aircraft wreaked havoc amongst Allied aircraft supporting the Arras offensive. The British lost over 200 aircraft and over 300 aircrew killed or captured.

Despite often finding himself outgunned, Stewart was credited with despatching five German aircraft between April and September 1917, qualifying him as an ace. These included three Albatros DIIIs – the aircraft that had dominated the skies during ‘Bloody April’ – and one Albatros DV aircraft. His Military Cross (MC) citation stated:

‘For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. He has done consistent good work for six months, both on escorts and offensive patrols, and has displayed great fearlessness and skill during severe fighting at close range with enemy machines, successfully holding his own, although on several occasions outnumbered by them.’

Military Cross awarded to Lieutenant Oliver Stewart, Royal Flying Corps, 1917

More details: NAM. 1998-05-27-1

Early years

Oliver Stewart (1896-1971) was born on 26 November 1896 in London. His father was Thomas Gibson Bowles, the founder of The Lady and Vanity Fair magazines. His mother was Rita Shell, who was Bowles’ mistress after the death of his wife, and later the editor of The Lady. She later changed her surname to Stewart.

In 1913 she entrusted her 17-year-old son with a press pass to cover ‘Ladies Day’ at Hendon Air Show. The aircraft and the fashionable ladies there entranced Stewart, and a fascination for both would stay with him in the eventful years ahead.

Stewart trained as a musician, studying the flute at the Royal College of Music. At the outbreak of the First World War, he joined up, following his brothers into the infantry. He writes in his memoir, Words and Music for a Mechanical Man (1967), that musicians at this moment were ‘useless people, only to be praised when they renounced their art and joined the forces’.

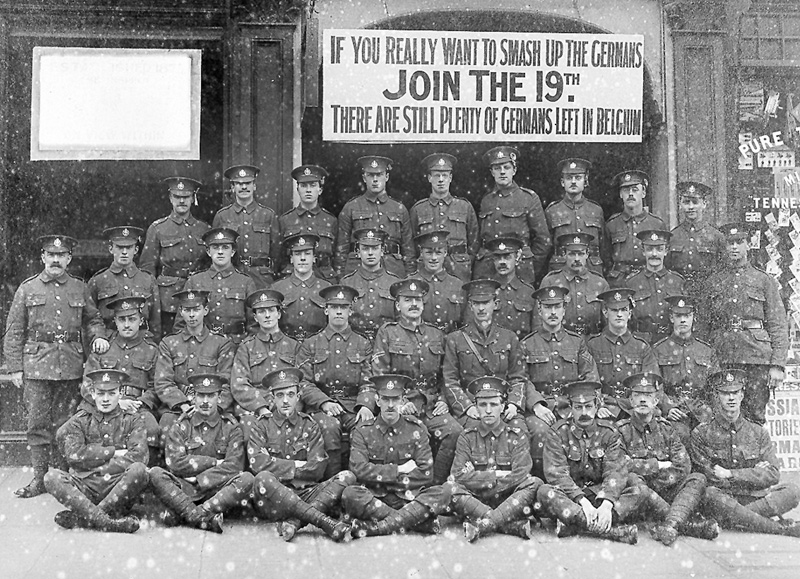

A recruitment team from The Duke of Cambridge’s Own (Middlesex Regiment), c1916

More details: NAM. 1993-04-197-1

Army life

Stewart enlisted with the 2/9th Battalion of The Duke of Cambridge’s Own (Middlesex Regiment) in October 1914 and served as a second lieutenant. But his enlistment in this second line unit was merely a means to an end, as his commission qualified him for secondment to the RFC.

Stewart disliked military discipline, writing:

‘The Army of that time believed in discipline and its form of discipline induced men to go forward to be killed in greater numbers and with greater certainty than anything else ever known.’

The monotony and the ‘monasticism’ of home service with the 2/9th caused Stewart to rebel. He bought a motorcycle to escape the confines of camp, recalling that ‘transport was the key to success in womanising’ and he had a determination ‘not to behave like an officer and gentleman’. At this time his home address was 10 Berkley Gardens, Campden Hill, Kensington.

Flight school

Stewart’s application to the RFC was finally granted in late 1915 and he joined other trainee flyers at Thetford Flying School in 1916. The flying instructors had a ‘kill or cure’ approach to training their young students who they referred to as ‘huns’, the popular slang for Germans. Stewart recalled that it took ‘an iron will, a thick skin or else utter fatalism to go through the training without becoming suicidal’.

A Royal Flying Corps recruit undertaking machine gun training, c1916

More details: NAM. 2001-06-134-35

Stewart qualified for his aviator’s certificate in a Maurice Farman aircraft and also trained on the Avro 504. The latter was ‘like a transparent dress, a covering which at once concealed and revealed the excellence of the body beneath’.

Stewart gained his hard-earned wings and qualified as a pilot in March 1916. Unlike the stereotype of the short-lived RFC pilot, he gained considerable experience while stationed at the Royal Aircraft Factory at Farnborough. Ferrying a variety of aircraft back and forth across the English Channel, Stewart developed his own flying code, a generic approach to flying any sort of aircraft.

Western Front

Stewart was eventually posted to France in January 1917. Initially serving with 22 Squadron, he was soon shocked by the horrors of the Western Front when compared to the ‘casual hedonism’ of life at Farnborough.

After an inauspicious start to combat flying, when he had to carry out a forced landing in his FE2b aircraft, he was soon transferred to 54 Squadron, operating nearer the front.

‘Stewpot’ Stewart flew escort for photographic missions over enemy lines in the popular Sopwith Pup or Scout – a light, single-engine bi-plane armed with a Vickers machine gun. These were hazardous sorties as the slow and steadily moving reconnaissance aircraft drew heavy German anti-aircraft fire from the ground and the unwanted attention of enemy fighters from above.

He was exasperated by the crude tactics that led to the near destruction of units like 22 Squadron, calling the flights a ‘deliberate quest for destruction’.

Affairs of the heart

When not flying, Stewart chased his other passion: women. Describing his depression after a dogfight with German aircraft, he explained how it was relieved by a stint of leave in Paris, ‘a city of beautiful women and of love’. Stewart’s womanising at home and abroad was extensive.

His memoirs show how, by 1917, social and moral barriers were gradually breaking down in England and France. He describes the abundance of unattached women available at Maxim’s Restaurant in Paris, but also how the parents of a French girl in Amiens, after taking tea with him, casually promoted her prostitution in the family home.

Test pilot

Soon after winning his MC he returned to England and was posted to the Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment at Orfordness. Eventually promoted to major in June 1918, Stewart’s interest in the design and manufacture of aircraft and the science behind flying increased as he tested a wide variety of aircraft and equipment.

He received an Air Force Cross for his contributions and eventually commanded the Orfordness establishment. While there, Stewart’s other interests led him to reconnoitre the surrounding area from the air, identifying a bungalow for let, in which he could set up a ‘girlfriend’.

Air Force Cross awarded to Major Oliver Stewart, Royal Flying Corps, 1918

More details: NAM. 1998-05-27-2

After the war

Stewart’s wartime experiences left him ‘permanently marked’; he could not afterwards look upon the actions of the politicians or the military men as ‘anything but evil’. The death of one brother, and the serious wounding of another, contributed to his bitterness about the war.

Stewart decided to leave the forces, not least because of the ‘hideous garments’ issued to the newly formed Royal Air Force (RAF). He made a brief and unsatisfying return to music, but the financial and other benefits of a service career proved too much of a temptation. Stewart explained his decision with the equation:

‘Money = Sex x Satisfaction’

He re-joined the RAF as a regular officer at the rank of flight lieutenant. Posted to Martlesham Heath as a test pilot, he assessed the speed, rate of climb and engine performance of single-seat fighters.

Stewart also championed innovation in aviation, developing a crash-proof safety fuel tank and supporting Oliver Sutton’s design for a quick release safety harness. Sutton was a fellow ace from 54 Squadron who was later killed in an accident at Martlesham Heath.

At Martlesham, Stewart met the legends of British aircraft manufacture including Frederick Handley Page, AV Roe, Bob Blackburn, Oswald Short, Geoffrey de Havilland and fellow motoring enthusiast, Harry Hawker.

Stewart’s love of motoring and motor sport led him to borrow a Bristol Fighter and fly over to the Brooklands racing circuit, for which he was soundly reprimanded.

Around this time, he met and married a French woman. This success in love was matched by the publication of his first, ‘worst and most successful’ book about motoring. With his reputation as a writer established, and the fear of a foreign posting and separation from his wife on the horizon, Stewart left the RAF in 1921. He settled at 17 Trafalgar Road, Twickenham.

Journalist

He began a new career as a journalist, writing for a variety of newspapers and journals including 11 years with the The Morning Post.

From 1939 until 1962 he was the editor of Aeronautics magazine. His books included Aerobatics: A Simple Explanation of Aerial Evolutions, Of Flight and Flyers, and his autobiography, Words and Music of a Mechanical Man.

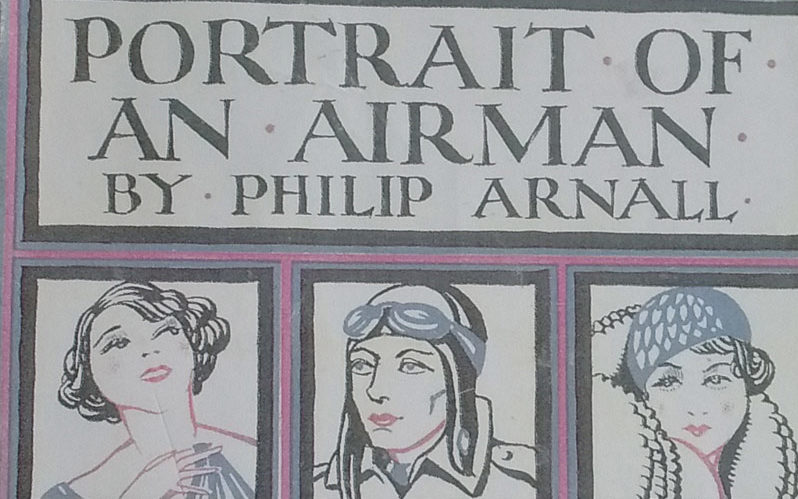

Under the pseudonym Philip Arnall, Stewart penned a rather risqué novel entitled Portrait of an Airman. This clearly echoes his own memoir, describing a young pilot’s escapades in the air, and in and out of the bedroom.

Stewart died in 1971, having lived long enough to see the advent of the jet age, including the first flights of Concorde and the Harrier jump jet.

His love of aviation stayed with him throughout his life, despite his early realisation that ‘aeroplanes were idiosyncratically homicidal’.

Explore further

- Article: Other Soldier Stories

- Article: Royal Flying Corps

Explore the map for similar stories

Lieutenant Oliver Stewart - Kensington, London

First World War in Focus

First World War in Focus