As a Forward Observation Officer with the Royal Artillery, Lieutenant Richard Barrett Talbot Kelly had a front row seat at the Arras offensive. His watercolours, drawings and published memoirs illustrate how the battle descended into a bitter stalemate on the ground and a bloody conflict in the air, dragging on until 16 May 1917.

The opening days of the Battle of Arras in April 1917 had turned out to be an unexpected triumph for the British Army on the Western Front, with troops advancing far further than anticipated. But, as had happened so many times before, the army struggled to convert initial success into a breakthrough.

Talbot Kelly’s job during the battle was to watch where artillery shells fell. This afforded him an exceptional view of the logistical and tactical struggle that unfolded. As a keen artist, he illustrated the battle through watercolours and drawings in a graphic cartoon style.

Tactical struggle

The initial British attack yielded an advance of five miles and the taking of enemy positions with few casualties. It also achieved its strategic objective of drawing German troops away from the River Aisne in advance of a French attack. But success rapidly turned to failure when the British found that they could not exploit their victory.

Richard Talbot Kelly, who took part in the opening stages, was quick to recognise that the army had not planned to support such an advance.

‘We had advanced so far and so quickly that our infantry outposts were now beyond the extreme range of their own field guns, so that we waited expectantly for our cavalry to come up and exploit the complete break in the German defensive system. But they did not come.’

The British success had created a tactical problem. Troops had moved beyond the range of reinforcement, and supply lines were unable to support them.

The High Command faced a choice. They could allow the exhausted troops to push on or remain in place until reserves could arrive, risking an enemy counter-attack before they turned up. Or they could give up ground taken and withdraw to a safer, supported position.

Richard’s memoirs reveal their fateful decision:

‘That night our outlying patrols were actually withdrawn, in spite of protests, so that they could be covered by our guns, and the positions we gave up that evening we later had to fight four months to regain.’

More details: NAM. 1994-12-20-1

The sudden flurry of snow on the first day of the battle had initially helped the British take their enemy by surprise. But the freezing weather lingered, causing poor visibility and difficult fighting conditions.

‘It was very cold, raining and snowing alternatively, and high up on the downs there was no cover of any sort from the bitterness of the wind.’

To make matters worse, after recovering from their early defeats, the Germans re-organised their defence, occupying reverse slope positions. These were much harder to observe and attack, and reduced the effectiveness of artillery fire.

The British launched several limited attacks, taking some ground. But the attempts became increasingly costly. Richard witnessed one of these advances from his forward observation post:

‘The noise of the German machine guns was completely inaudible and, as I watched, the ranks of the Highlanders were thinned out and torn apart by an inaudible death that seemed to strike them from nowhere. It was peculiarly horrible to watch… these frightened men dying in clumps in a noiseless battle. The attack failed completely.’

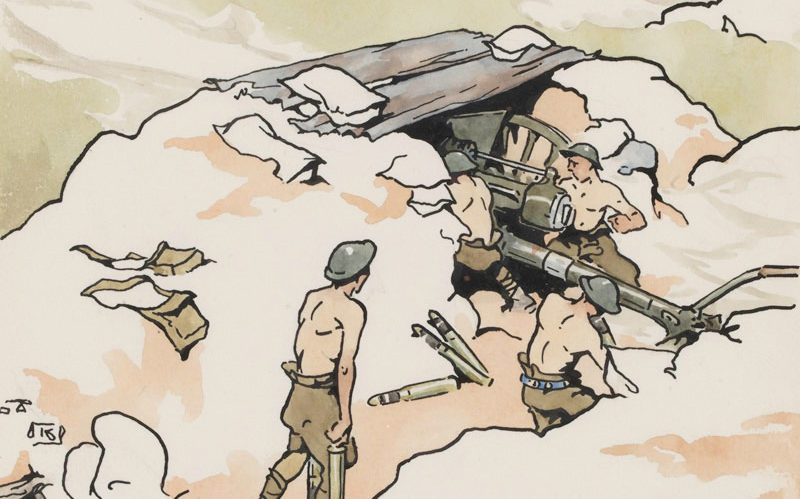

‘Bristol Fighter ‘ground strafing’, Arras Front 1918’ by RB Talbot Kelly

More details: NAM. 1994-12-30-1

Air struggle

In late 1916 Germany had achieved aerial dominance over the Western Front. But the reconnaissance capability of aircraft was too valuable for the British to forego during a battle on the scale of Arras.

By 1917 the army’s air wing, the Royal Flying Corps (RFC), had adopted an offensive strategy despite being woefully outclassed by the enemy. For the duration of the Battle of Arras the RFC flew over enemy lines and battled the German Luftstreitkräfte, who were equipped with better (but fewer) aircraft. They suffered huge losses, losing over four times as many machines as the Germans and 400 men in the process.

‘The skies were filled with aeroplanes, and for the most part it was generally our own machines that we saw shot out of the sky in flames by the superior Albatros fighters of the Richthofen Circus.’

In early May 1917 Richard witnessed some of the most dramatic moments of the Arras air struggle. His daily diary was full of air fights. On 5 May he watched Britain’s highest scoring fighter ace (at the time) Captain Albert Ball make a forced landing right in front of him.

Just two days later he watched Ball head up an attack on a squadron led by Manfred von Richthofen, the Red Baron. Ball was killed when his aircraft crashed after engaging the enemy. Richard recalled:

‘The news of his death spread throughout the British Army astonishingly quickly and although none of us knew him we shared the depression of his loss.’

The life expectancy of a British pilot over Arras was just 17.5 hours and the slaughter in the skies became known as ‘Bloody April’. The offensive almost destroyed the morale of the Royal Flying Corps, but they still succeeded in gathering valuable intelligence of enemy positions.

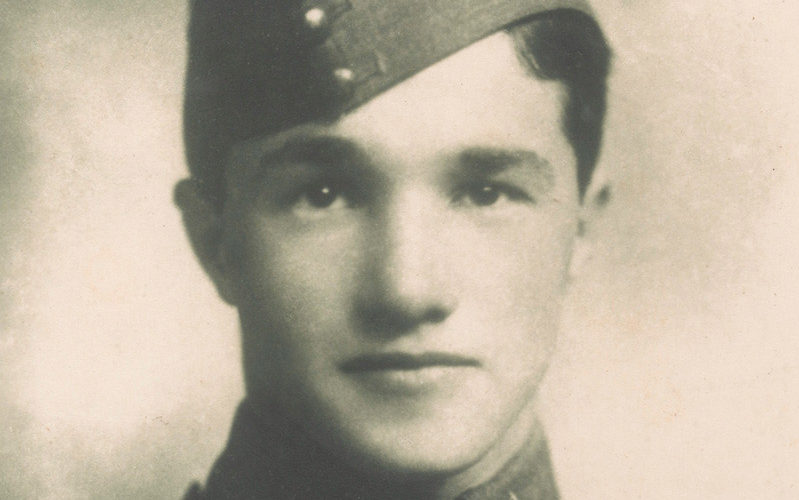

Captain Albert Ball, 1917. Richard witnessed several of his last air battles over Arras

More details: NAM. 1981-03-28-129

French mutiny

On 16 April the French launched an offensive along the River Aisne, from Soissons to Reims. It was intended to support the British at Arras. The French General Robert Nivelle was convinced he could deliver a war-winning breakthrough.

But Nivelle’s offensive failed spectacularly. Strategic objectives were not achieved and the French suffered massive casualties. By the end of April, the attack had ground to a halt and the fragile morale of the French soldiers, who had already suffered through the battles of Verdun and the Somme, was broken by this latest failure.

Mutinies broke out from early May. Men refused orders to attack, or arrived at the front lines drunk and without weapons. Nivelle was swiftly removed from command.

More detail: NAM. 1994-12-61-1

Run-down and pretty tired

By 16 May, the official end of the battle, the Arras front had returned to the day-to-day stalemate of trench warfare. Attacks were later mounted against the Hindenburg Line and at Lens over the summer by the British and Canadians. But these had little impact.

The British were unable to break through at Arras. But they had made some significant advances and captured 254 German guns. Unfortunately, these gains were offset by the failures of the French, and the high British casualties in the later stages of the offensive.

In the wider context of the Western Front, the battle had little strategic or tactical impact. But the early stages of the attack demonstrated that the British Army had learned some tactical lessons from the Somme offensive and could exploit new set-piece attacks with success.

As for Richard, he had a lucky escape in his dug-out towards the end of the battle:

‘One morning I woke up feeling an unusual weight on my stomach and found during the night a German 4-inch shell had passed through the middle of the corrugated iron without exploding…’

He was sent away for a fortnight’s rest shortly after, avoiding the last days of the battle. He recalled feeling ‘rather run-down and pretty tired’.

Biography

Richard Barrett Talbot Kelly (1896-1971) was the only son of the artist Robert Talbot Kelly and his wife, Lilias Fisher Kelly. He was born on 20 August 1896, in Birkenhead, Cheshire, and lived in Rochdale, Lancashire.

Richard would later become an artist in his own right, particularly known for his paintings of birds. He developed a love of natural history while holidaying with his mother’s family in Scotland.

Richard was educated at The Hall School in Hampstead. He later attended boarding school in Rottingdean, before finishing his education at Rugby School in Warwickshire. War broke out during his final year of school in 1914.

‘I heard the news of the British declaration of war at a country house party at the end of a dance, after two happy, carefree days at the start of the summer holidays… Next day my father asked me what I intended to do. I said I supposed “go and fight”.’

The 18-year-old Richard cast aside his aspiration of attending Oxford University in favour of a military education at the Royal Academy at Woolwich. After passing the entrance exam, he became an artillery cadet, earning a commission as a second lieutenant with the Royal Horse Artillery on 22 April 1915. Shortly after, Richard transferred to the 52nd Brigade of the Royal Field Artillery. He arrived in France in May 1915, serving in the 9th (Scottish) Division.

As part of an 18-pounder gun battery crew, Richard took part in many of the major offensives of the Western Front, including the Battle of Loos (1915), the Battle of the Somme (1916) and the Battle of Arras (1917).

He regularly served as a Forward Observation Officer (FOO), tasked with spotting where artillery shells landed. The unique vantage point that this job provided obviously inspired his illustrations – though some of the drawings suggest he had a few dangerous encounters with shellfire!

More details: NAM. 1994-12-59-1

Richard was wounded during the preliminary bombardment at the Battle of Passchendaele on 5 August 1917. He fell victim to German counter-battery fire, which was particularly deadly to the British artillery during the early stages of the battle.

In the last page of his memoirs he recalls standing and talking to the captain of another battery, when a shell burst nearby. He appeared to have survived unscathed, but the force of the blast had actually caused internal damage. Richard described how it had ‘severely concussed all my insides’. He was sent home to recover.

‘One does not hear the shell that gets one. If the ground had not been a bog and as soft as it was it is absolutely certain that I would have been blown to bits.’

Richard returned to France in April 1918. After the devastation caused by enemy artillery at Passchendaele, the British were seeking ways to hide their guns from aerial reconnaissance. Richard was tasked with studying concealment techniques.

He taught camouflage to the School of Artillery in Larkhill and became so fascinated by aerial tactics that he applied to join the Royal Flying Corps. Unfortunately, he was posted to the flying school just as the war ended, so never realised his dream of flight.

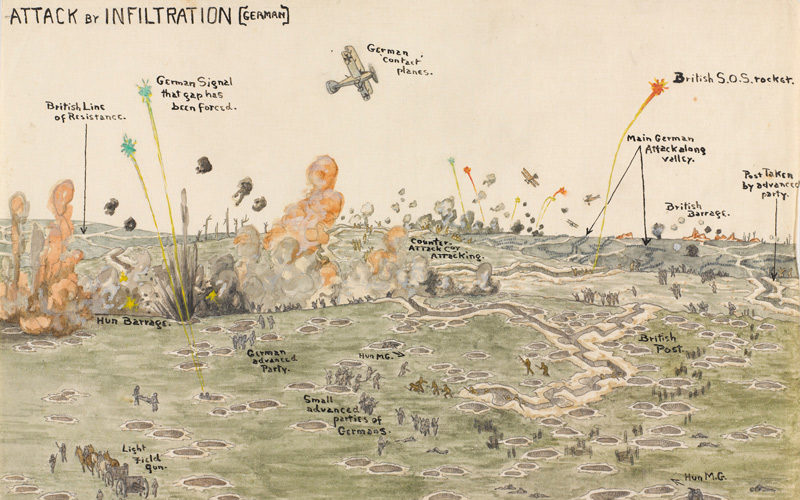

‘Panoramic view of attack by infiltration (German, July 1918)’ by RB Talbot Kelly

More details: NAM. 1994-12-62-1

Richard continued his military career after the war, serving again briefly with the Royal Artillery in India, and manning an anti-aircraft battery. At the same time, he began to exhibit his paintings of birds, becoming a recognised artistic talent in 1923, and being elected to the Royal Institute of Watercolour painters in 1925.

Richard married Dorothy Bundy in 1924, and left the army in 1929 to become Director of Art at his old school in Rugby. He had two children, Chloe and Giles, who also became artists.

During the 1930s Richard worked steadily on his artistic career. He published several books of bird paintings before being recalled to the army in 1939 to become Chief Instructor at the War Office Camouflage Development and Training Centre in Farnham. He held this post for the duration of the Second World War (1939-45) and was made a member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) for his service.

Richard continued to teach at Rugby until 1966, although during this time he also tried his hand at being a museum professional. He curated the Natural History room in Warwick Museum and the Natural History Gallery at the National History Museum of Uganda.

On his retirement from teaching, Richard moved to Leicester and continued his heritage career, assisting the local museum with their Natural History collections. He died in June 1971.

Explore further

- Article: Other Soldier Stories

Explore the map for similar stories

Lieutenant Richard Talbot Kelly - Birkenhead, Cheshire

First World War in Focus

First World War in Focus