Charles Stooks (seated front left) with a colleague and their servants, Chakrata, 1898

More details: NAM. 2007-05-44-1

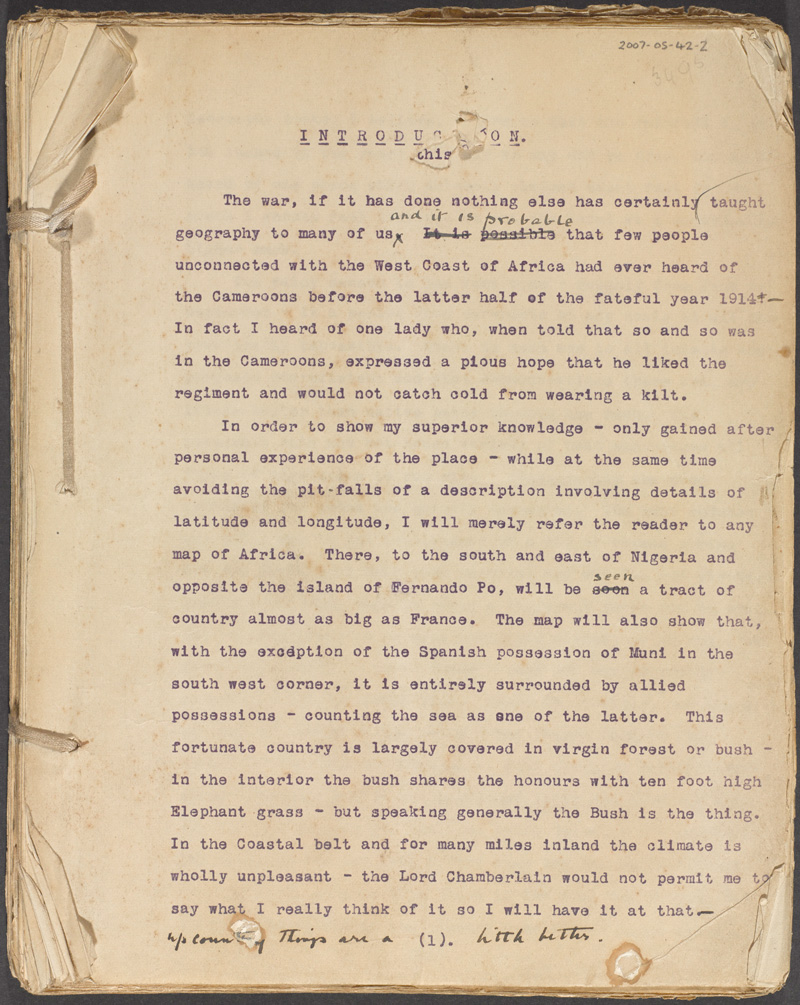

The diary of Major Charles Stooks of the 5th Light Infantry reveals the difficulties faced by those involved in the final conquest of Germany’s West African colony of Kamerun.

Enemy colonies attacked

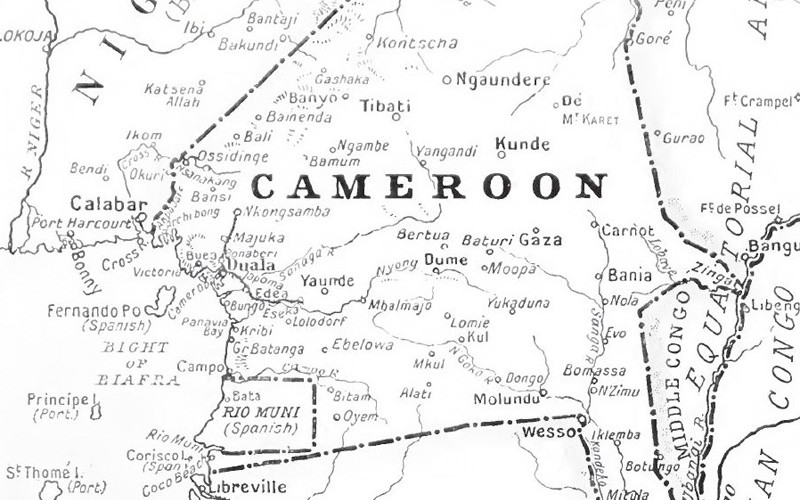

In February 1916 the Allies finally completed the conquest of German Kamerun (Cameroon). The contribution of Britain’s West African and Indian troops was crucial in securing this victory. Both their role, and the wider experiences of all those fighting in one of the war’s forgotten side-shows, are revealed in the diary of Major Charles Stooks of the 5th Light Infantry.

Germany’s West African territories consisted of Togoland (now Togo) and Kamerun (now Cameroon). They were poorly defended and surrounded on all sides by French and British colonies. Togoland was conquered in August 1914 by forces from the British Gold Coast (now Ghana). Three British columns then attacked Kamerun from Nigeria, but all three were defeated by a combination of rough terrain and German ambushes.

Opposing forces

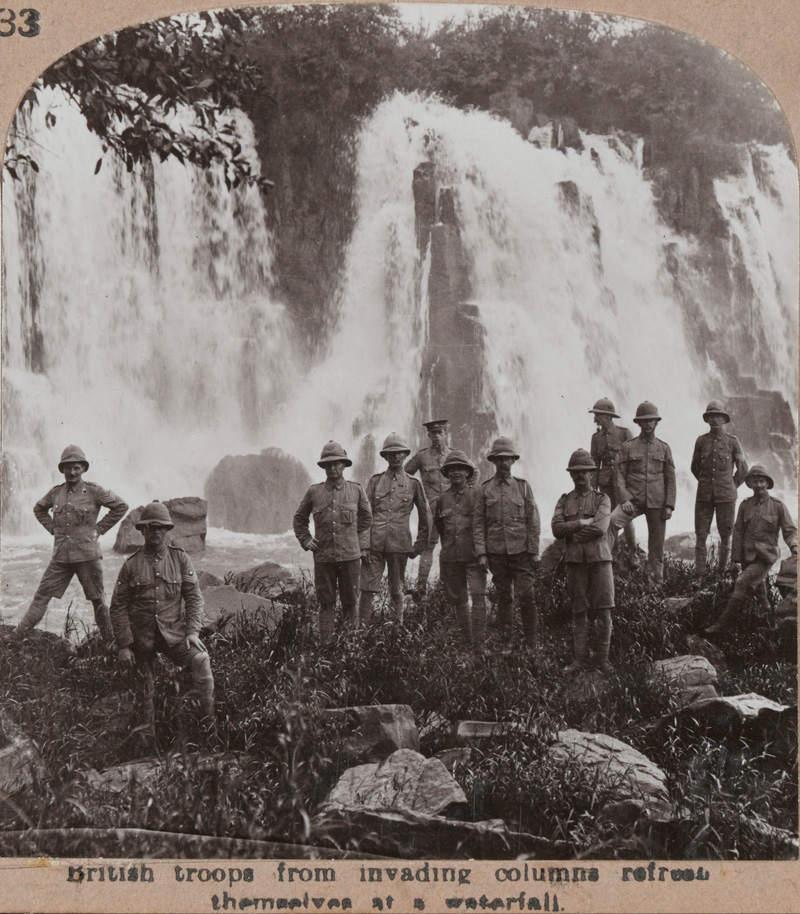

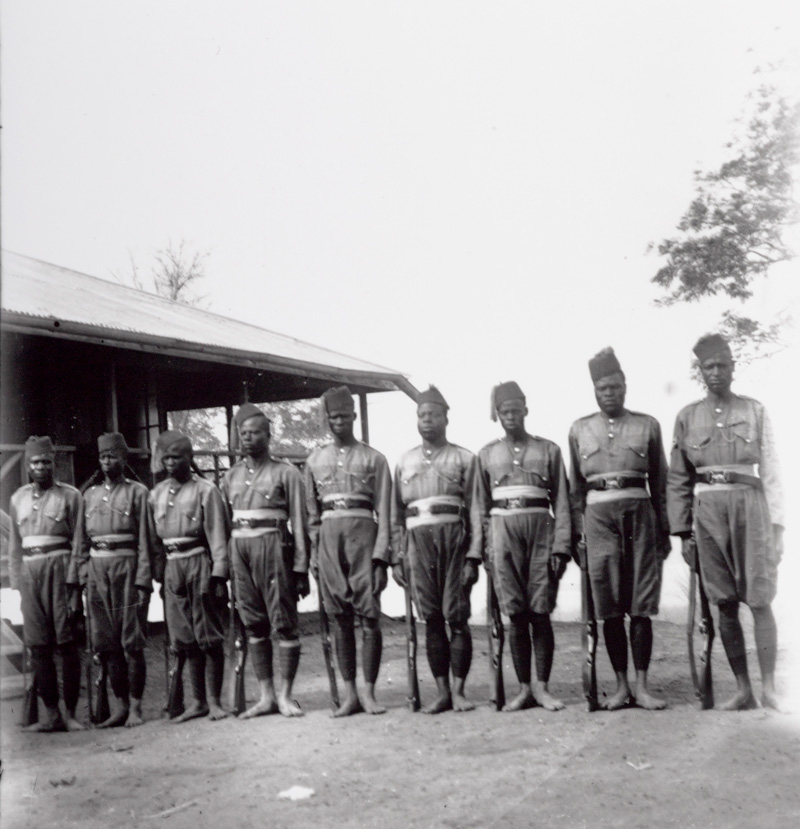

Kamerun had a garrison of about 1,000 German soldiers supported by about 3,000 African troops. British forces included the Nigeria and Gold Coast Regiments of the West African Frontier Force, and eventually Indian and British troops.

They outnumbered the Germans and were supported by an ‘army of carriers’. Each man ‘takes a 56lb [25kg] load on his head. And we have’, wrote Stooks of his column, ‘over 1,000 non-combatants to our fighting force of 500.’

Harsh climate and disease

The campaign was fought in inhospitable jungle conditions:

‘The rainy season is a period when movement on any scale is practically impossible. Roads as such are to all intents and purposes non-existent and what communications there are, are little better than native paths through the bush… The heat reduces the white man to the consistency of a bit of chewed string and the mosquitoes make high carnival and wax fat and strong… It has been raining for weeks and every bit of ground is either marsh or a roaring torrent, when it is not actually raining a thick mist hangs over the place.’

This climate, along with virulent disease and dangerous wildlife, caused more casualties than the enemy:

‘Malaria… has been rampant, and I fear that certain men whose luck it was to be left in unhealthy spots, will feel the effects for the rest of their lives… The men have suffered from fever, daily doses of quinine to sick and sound alike seem to be doing them good in spite of the wet…

The trouble later when the place begins to dry up will be the jigger flea, a pleasing little animal which attacks one’s feet, and having burrowed into the flesh proceeds to lay eggs. If this is not dealt with well and truly early disaster results, and a man can be incapacitated for a long time. The native of the country is an expert in detecting and removing these honorary members and we have instituted a daily inspection of the men’s feet by African stretcher-bearers and machine gun carriers.’

Campaign renewed

In September 1914 the French attacked south from Chad and captured Kusseri in northern Kamerun. Early in September 1914, a Belgian-French force from the Belgian Congo (now the Democratic Republic of Congo) captured Victoria (now Limbe) on the coast.

With the aid of four British and French cruisers acting as mobile artillery, this force captured the colonial capital of Douala on 27 September 1914. The Belgian-French troops then followed the German-built railroad inland, beating off counter-attacks along the way.

By November 1914, Juande (now Yaounde) was captured and most of the surviving Germans had either retreated into neutral Rio Muni (now Equatorial Guinea) or to the interior, where they held out in posts at Banjo, Fumban, Jokoo and Garua. During the next year the re-inforced Allies gradually captured these.

Needle in a haystack

Stooks described the difficulty of this style of fighting:

‘It is like looking for the proverbial needle… It is eerie work walking along a narrow bush track, the trees meeting overhead and the grass disputing your right of way, it is still more disquieting when there may be a selection of armed Huns round the next corner with a machine gun nicely covering the path. Chances have to be taken in this sort of country, and our protective measures are practically confined to an advanced guard on the path itself.’

Securing territory

As territory was conquered it had to be secured:

‘Another German post and rest village occupied today with little trouble. We got here [Sanschu] about 10.30am having left Mwu river camp at 4.30. A long tedious day – the actual distance being only about six miles [10km]. Mwu river crossing has been left in charge of a havildar [Indian soldier] and 12 men. It is a nuisance having to drop these little posts on our lines of communication, but at present it cannot be helped. We don’t know that there may not be an odd party of Huns wandering about the country, and a full convoy would make a nice haul for any such, so essential spots have to be guarded.’

Ambush

The Germans had ‘plenty of kick still left in them and they put up a stout resistance at more than one place, notably on the Juande Road and at Banjo’. A typical engagement took place near the village of Fongwini on 25 October 1915:

‘Suddenly a single shot was heard far up towards the head of the advanced guard. About 30 seconds later a furious fusillade opened the whole length of the column from the hills across the river. Our guns were a fair mark, lying on the road as the carriers had put them down when the halt was signalled and a native corporal and several carriers were hit. Luckily, one of our Maxims was already in position on the road near the corner, and opened fire – the other one was dragged up the slope above the road and got into action from there. The West Africa Regiment’s Maxims in front also began to bark…

Those men who could get anything of a view opened fire from the grass at the sides of the road. It was an unfortunate position though, owing to the twisty nature of the road, not many men could use their rifles to start with. However, this was soon remedied by moving sections on to the hill above the road, and in a short time a heavy rifle fire was being directed on to the opposite hills. Very little could be seen, but it was evident that the Huns were occupying a small village about 800 yards across the river.

Our guns now took a hand in proceedings… The first shell that went screaming towards the German position… put a different complexion on the affair, and caused a certain amount of movement to the rear on the part of the German natives to be apparent. The Huns had evidently calculated on getting our column, and especially our guns, just as they had turned the corner of the road. This would have brought them under almost point blank fire and left them entirely exposed. As it was the guns were some distance from the corner and partly hidden by grass. The baggage carriers in the rear also came in for their share of trouble, and promptly downed tools and took to the grass – small blame to them either poor devils. The combined efforts of guns, Maxims and rifles in time caused the German fire to slacken, and finally die away…

Nothing could be seen of the enemy though his fire had ceased, and it was probably that he had gone. The means by which this disappearing trick was executed was discovered later on. The Huns had beaten down lanes through the grass along which their various parties could retire without showing themselves, and with no undue exertions from having to force their way through the tall grass…

The total casualties in the column were seven killed and 23 wounded. There ought to have been more, but luckily the German shooting was not good.’

Surrender

After many such skirmishes and long marches through inhospitable terrain, the last surviving German post surrendered on 18 February 1916. German rule in Kamerun was at an end.

Biography

Charles Sumner Stooks (1875-1953) was born at Longbridge Deverill, Wiltshire, on 23 December 1875. He was the eldest son of Reverend Charles Drummond Stooks and Alice Louisa Sumner. Charles had three younger brothers and three younger sisters. In 1881 the family was living at Crondall in Hampshire where Charles’s father was curate of Crondall church. They later moved to Yately, also in Hampshire.

Charles Stooks was educated at Cheltenham College and the Royal Military College Sandhurst. He was commissioned as second lieutenant in the South Wales Borderers on 28 September 1895. He was promoted to lieutenant in April 1897 and transferred to the Indian Army in 1899 joining the 20th Madras Light Infantry (re-named the 62nd Punjabis in 1902). By September 1904 he had risen to the rank of captain and the following year transferred to the 5th Light Infantry, going on to serve in China in 1901.

Stooks was married to Eileen Alberta Strover, the daughter of Major-General George Strover, at St John’s Church at Nowgong in Bengal on 12 September 1910. Their children were Henry Joseph, Robert Joseph and Gertrude Stooks.

In October 1914 Stooks’s unit left Madras for Singapore. While there it was involved in a mutiny caused by poor communication between the Muslim sepoys and their officers, slack discipline, an unpopular commanding officer and the influence of Indian nationalist and pro-Turkish agitators. The revolt was put down, but not before the rebels had killed several civilians and British soldiers, and attempted to release interned German sailors. Over 40 mutineers were executed and 130 imprisoned.

In July 1915 the remnants of the 5th Light Infantry, seven British and Indian officers, and 588 sepoys sailed from Singapore for West Africa. They served with the Bare Column in Cameroon between September 1915 and February 1916.

Following the German surrender in Cameroon, Stooks’s regiment was transferred to German East Africa (now Tanzania). In July 1916 he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order during an action at Manza Bay, north of Tanga. His citation stated: ‘For conspicuous gallantry in action. He showed marked courage and skill in commanding the advanced guard under machine-gun and heavy rifle fire. He was severely wounded.’

In December 1917 the 5th Light Infantry briefly moved to Somaliland, before returning to India during January 1918. The regiment was disbanded in 1922 as part of the restructuring of the Indian Army.

Stooks retired with the rank of lieutenant-colonel and resided at Yately. He died on 7 May 1953 at Bromhams in Yateley. His funeral took place at Yately church and was followed by a cremation.

Explore

- Article: Other Soldier Stories

Explore the map for similar stories

Major Charles Stooks - Yateley, Hampshire

First World War in Focus

First World War in Focus