Captain Percy Ingpen, 1/8th Battalion The Duke of Cambridge’s Own (Middlesex Regiment), 1915

More details: NAM. 1992-08-93-58

The diaries and papers of Major Percy Ingpen of 1/8th The Duke of Cambridge’s Own (Middlesex Regiment) bring to life a battle that has come to symbolise the horrors of trench warfare.

Explosion at Messines

The British began yet another assault on the German lines on 7 June 1917 with a series of huge mine explosions at Messines Ridge in Flanders. These killed around 10,000 Germans and totally disrupted their lines.

Following the detonation of the mines, nine Allied divisions attacked behind a creeping artillery barrage, supported by tanks. They gained their initial objectives due to the devastating effect of the mines. They were also helped by the German reserves being positioned too far back to intervene. German counter-attacks continued until 14 June, but by then the entire Messines salient was in Allied hands.

New offensive

Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig intended to use the captured ridge and salient as a launch point for another offensive. This operation aimed to drive a hole in the enemy lines, advance to the Belgian coast and capture the ports, thus removing the German submarine threat to the British war effort. An attack would also take the pressure off the French. Their army had experienced a series of mutinies following the disastrous Nivelle Offensive and needed to recuperate.

Fatal delay

Unfortunately, Haig was persuaded to delay this new assault. General Herbert Plummer, the Second Army commander, believed the ridge first had to be consolidated. At the same time, Haig’s political superiors were reluctant to provide him with new troops for the offensive.

By the time Haig received the extra men he needed, the time for exploiting the breakthrough was long past. The Germans knew the offensive was coming and moved more troops in to bolster their defences. They also constructed a formidable system of pillboxes made from reinforced concrete. These protected front line troops from the Allied bombardment and were positioned to provide mutually supporting fire.

More details: NAM. 1994-04-390-5

Pilckem Ridge

Despite this, the Third Battle of Ypres (or Passchendaele) was launched on 31 July 1917 after a two-week preliminary bombardment that again failed to destroy the heavily fortified German positions. The initial Anglo-French attack (the Battle of Pilckem Ridge) was hampered by heavy rain and failed to breakthrough, but the Allies captured a substantial amount of ground from which they hoped to renew their assault.

Ingpen’s battalion was at Wancourt near Arras during the Messines and Pilckem Ridge fighting, but moved into the Ypres Salient in early August near Ouderdom. On 12 August the 1/8th battalion, along with the rest of 56th Division, relieved troops on the recently captured Westhoek Ridge in preparation for an attack on 16 August.

During this time Ingpen’s diary noted that there was ‘a lot of aerial activity’ and their ‘camp area was badly bombed’. He also recorded the heavy thunderstorms that were to have such an effect on the forthcoming fight. On 15 August the battalion ‘assembled for attack’ but were heavily shelled.

Observing the opening bombardment during the Battle of Langemarck, 16 August 1917

More details: NAM. 1978-11-157-24-36

Langemarck

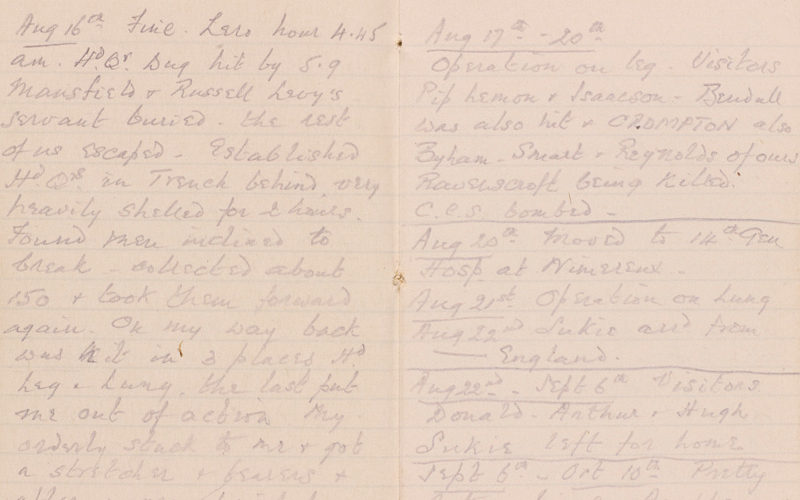

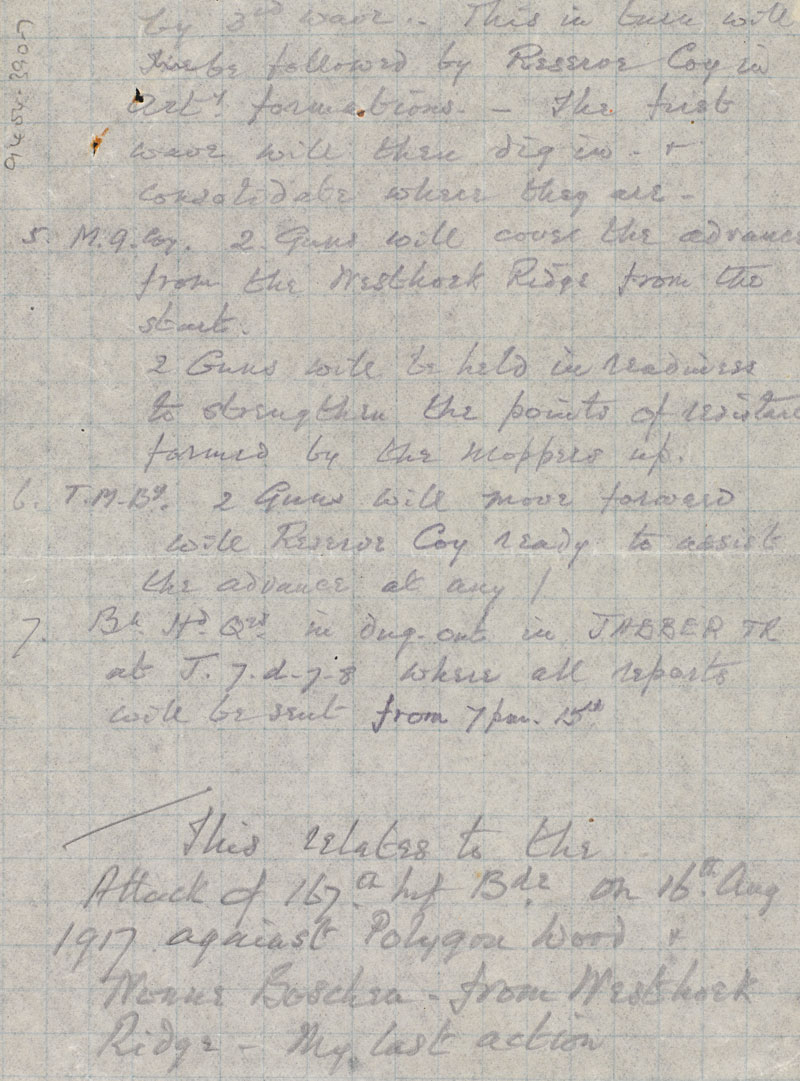

The Battle of Langemarck (16-18 August) saw two days of fierce fighting which resulted in small gains for the British, but heavy casualties. At the very start of the battle Ingpen’s headquarters dugout was ‘hit by a 5.9 shell’; two men were killed but ‘the rest of us escaped’.

His battalion (with the rest of 167th Brigade) then advanced in three waves against part of Polygon Wood and Nonne Bosschen Wood using the ‘leapfrog system’. This envisaged the first wave taking an objective and the next wave then passing through to the next. The orders given to Ingpen show that success depended on perfect organisation and timing to match the brief interludes when the creeping artillery barrage lifted.

Between the British and German lines was a valley and as the men reached this low ground they came to a broad expanse of mud and water. Ingpen noted that ‘it was almost impossible to walk with any degree of safety. It was just a question of keeping to the lips of shell holes. These, in most cases, had merged into wide extended holes filling with water. Ahead, as far as I could see, conditions were the same, some of these water-filled depressions resembled small lakes, the result of clusters of shells falling in a limited area’.

The attacking troops had to bear off left and right and began to fragment. They also lost touch with their barrage. Heavy machine gun fire took a heavy toll as repeated attempts to push on were repulsed. The Middlesex then pulled back as their flanks became exposed, but the line of posts they took up was machine-gunned by German aeroplanes. There they remained for most of the afternoon.

‘Attending to wounded on the Menin Road, Ypres, during the stiff fighting around Zonnebeke’, 1917

More details: NAM. 1972-08-67-1-92

A period of heavy shelling then affected the men’s morale and members of several different units began to retire. Ingpen ‘found the men inclined to break and collected about 150 and took them forward again. On my way back I was hit in three places, the head, leg and lung. The last put me out of action. My orderly stuck to me and got a stretcher and bearers and after a very painful journey I arrived at 36 CGS [Casualty Clearing Station] pretty well done up’.

Ingpen’s intervention stabilised the line. ‘Three times the Huns countered utilising great forces, but our line remained firm and each successive threat was smashed. The enemy losses are indeed heavy’. But so were those of the 1/8th Battalion and included 11 officers and over 200 other ranks killed, wounded or reported missing.

Percy Ingpen was later awarded a second Distinguished Service Order (DSO) ‘for conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty’. His citation in ‘The London Gazette’ recorded:

‘During an action his battalion headquarters were demolished by shell fire, and he was only extricated with great difficulty. Though ordered to hand over his command, he went to the front-line trenches on hearing that the enemy was counter-attacking. He remained there until dangerously wounded, restoring confidence by his example at a most critical period.’

The struggle at Langemarck continued but the British were eventually forced back to their start lines by German counter-attacks. Attempts by the Germans to then advance further were stopped by artillery fire and the same muddy conditions that had so hampered the British.

Horse-drawn water cart stuck in the mud, St. Eloi, 11 August 1917

More details: NAM. 1978-11-157-4-25

Attrition

The foul weather and waterlogged ground forced the British to temporarily halt the offensive in the hope that the ground would dry out. But when it resumed strong German resistance, including the use of mustard gas, saw the operation grind to a halt in the shell-churned mud. By the time the Canadians had captured the town of Passchendaele on 6 November 1917 the British had advanced eight kilometres (five miles). Commonwealth and French losses approached 300,000. German casualties were 260,000.

The battle of attrition almost broke the resolve of both armies. But the Germans, with fewer men, could afford the casualties less than could the Allies. Nevertheless, Haig and the High Command have since been accused of continuing the offensive long after it was clear to many that men were dying for relatively little strategic gain.

Biography

Percy Leigh Ingpen (1874-1930) was born on 28 February 1874 in Holborn, London. He was the son of Robert Frederick Ingpen and Lilly Mary Ingpen. His father’s occupation was listed as ‘Gentleman’. Percy had a sister called Edith and his family lived at 95 Chancery Lane. He was educated at Charterhouse. By 1891 his family had moved to 46 Dollys Farm, Chobham, Surrey.

Percy attended the Royal Military College before being commissioned as a second lieutenant with the 2nd Battalion The Prince of Wales’s Own (West Yorkshire Regiment) in October 1894. Promoted to lieutenant in October 1895, he subsequently served in Gibraltar, Hong Kong, Singapore and Malaya prior to becoming captain in March 1901. Ingpen then served during the Boer War (1899-1902) and in Ireland. He was married to Eleanor Susan Lyall on 14 January 1899 at St Andrew’s Cathedral in Singapore. The couple had three children; Robert Lyall Leigh, James Percy and Margaret Eleanor.

In November 1914 Percy arrived with his battalion on the Western Front. Despite only holding the rank of captain he commanded the 2nd West Yorkshires from 10 January 1915 until 22 March. This included the Battle of Neuve Chappelle (10-13 March 1915) where he was awarded the DSO for leading two companies forward on 10 March to reinforce a recently captured position. He then defended this against repeated German counter-attacks while under constant artillery bombardment.

In June 1915 Ingpen was appointed brevet major and in September given command of a Territorial Force unit, 1/8th Duke of Cambridge’s Own (Middlesex Regiment). This was part of 56th (London) Division and Percy went on to lead it at the battles of Loos (1915) and the Somme (1916).

In October 1916 he was appointed to command the 56th Divisional Training School, but returned to his battalion in January 1917. He then fought at the battles of Arras (1917) and Passchendaele (1917). His diary also records that he sat as a judge on a military court martial for a case of desertion where the accused was convicted and shot by firing squad.

Ingpen’s leg and lung were subsequently operated on and he remained in the 14th General Hospital at Wimereux until October 1917 when he returned to England. A spell at No. 8 Hall-Walker Hospital for officers in Regent’s Park, London then followed. During his convalescence he was appointed an officer of the Belgian Order of the Crown. Percy was promoted to brevet lieutenant-colonel in January 1918 and awarded the Belgian Croix de Guerre in March that year.

He never fully recovered from his wounds, but later returned to the West Yorkshire Regiment, commanding its 1st Battalion in Germany and Ireland between 1923 and 1926 when he retired. Percy died on 24 August 1930 at Holmlea, St Peters-grove, York. He was buried at Fulford Water Cemetery in York.

Explore further

- Article: Other Soldier Stories

- Article: The Battle of Passchendaele

Explore the map for similar stories

Major Percy Ingpen - Holborn, London

First World War in Focus

First World War in Focus