Private Percy Ottley was killed during the Battle of Cambrai, an operation that witnessed several tactical innovations and which foreshadowed the mobile battles of 1918. This collection of objects reveals the story of his death and its impact on his loved ones at home. Similar stories were shared by hundreds of thousands of families across Britain.

Cambrai

While the attritional struggle at Passchendaele (July-November 1917) dragged on, the British High Command approved a plan to attack and encircle the German-held town of Cambrai. The operation would use cavalry, aircraft, artillery and infantry.

Cambrai was an important railhead, but was defended by the formidable Hindenburg Line, a system of concrete pillboxes, deep belts of wire and interlocking fields of fire.

A tank towing a heavy artillery piece captured at Cambrai, 29 November 1917

More details: NAM. 1959-05-55-3-6

On 20 November 1917, the Germans were surprised by a brief but intense artillery attack on a ten-mile front along the Hindenburg Line. Soon after, 350 British tanks advanced across the ground, supported by infantry. A creeping artillery barrage assisted their attack.

Many tanks were fitted with huge bundles of sticks, known as fascines, to be tipped into the deep ditches of the enemy lines. These would form bridges over which the following tanks could crawl. This initial attack went well with some units advancing more than five miles from their starting points. Thousands of enemy prisoners were taken.

German soldiers standing in front of knocked out British tanks, Cambrai, November 1917

NAM. 1985-08-28-40

Bourlon Ridge

One important position that had not been secured was Bourlon Ridge, which dominated the left of the large salient created by the attack. Reinforcements were now brought up by the British to attack it.

At 8am on 23 November 1917, 1st/14th (County of London) Battalion, The London Regiment (London Scottish), part of 168th Brigade, attacked Tadpole Trench near Bourlon Wood on the crest of the ridge. Despite suffering casualties from German machine-gun nests to the north, and from German artillery fire, they managed to take the trench system, capturing 70 prisoners, six machine guns and a trench mortar.

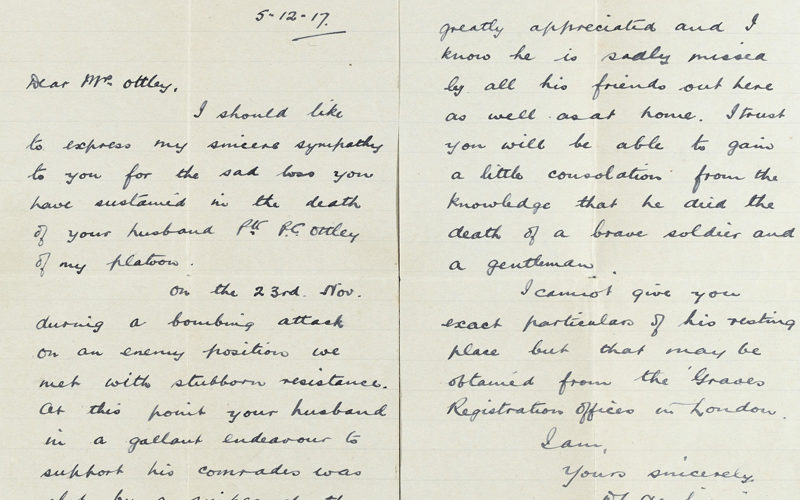

One of those killed during the attack was Private Percy Ottley. His commanding officer, Second Lieutenant D L Newbigging, wrote to his wife to express his condolences:

‘On the 23rd November during a bombing attack on an enemy position we met with stubborn resistance. At this point your husband in a gallant endeavour to support his comrades was shot by a sniper, death being instantaneous. His presence amongst us was greatly appreciated and I know he is sadly missed by all his friends out here as well as at home. I trust you will be able to gain a little consolation from the knowledge that he died the death of a brave soldier and a gentleman.’

More details: NAM. 2004-11-115-4

Counter-attacks

Throughout the day, and into the next morning, the London Scottish was subjected to German counter-attacks. Eventually they were forced by weight of numbers out of their hard-won position and retreated down its communication trenches.

Many were cut off from them and had to withdraw over open ground, suffering serious losses. Nevertheless, a new position was taken up and bombing blocks established that eventually held the enemy back until darkness ended the fighting.

The wider battle continued, but British progress slowed as German resistance increased. Units became isolated and there were communication difficulties amid the intense fighting. On 30 November the Germans launched a major counter-attack, using intensive artillery fire, gas attacks and infantry tactics that made use of infiltrating ‘storm troops’.

After heavy fighting, British forces, including the London Scottish, retreated from their salient, leaving them with only some of the gains they had made at the start of the operation. When the London Scottish was relieved on the night of 30 November it had suffered 61 killed, 282 wounded and 20 missing.

Overall, British battle casualties amounted to 44,000 killed, wounded or captured. The Germans sustained around 45,000 casualties.

German prisoners compelled to carry the wounded, Bourlon Wood, 1917

More details: NAM. 1972-08-67-2-141

New methods

Cambrai showed that the British could break deeply and quickly into the German defences with relatively few casualties, but also that better communication was needed if reinforcements were to exploit the success. The British also used new methods such as sound ranging and flash spotting to pin-point enemy guns, infantry-tank co-ordination and close air support.

In many ways the Cambrai fighting was a precursor of the Allies’ successful ‘all arms’ battles of 1918, in which artillery, armour, aircraft and infantry effectively worked together.

More details: NAM. 2007-03-7-64

Biography

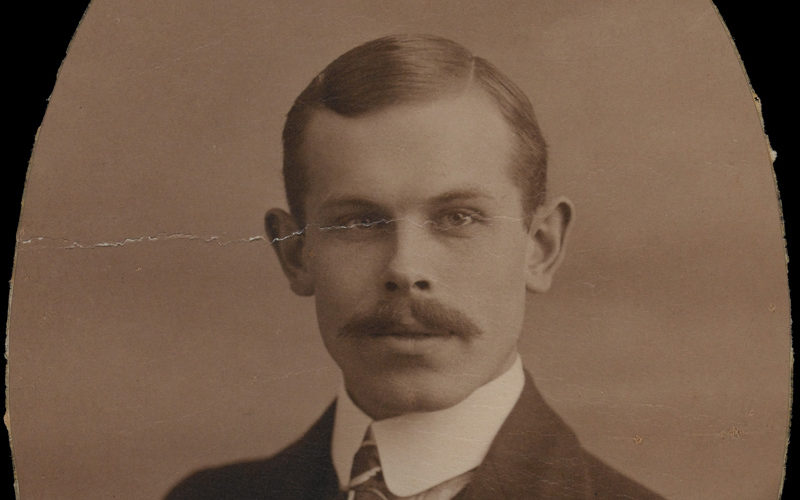

Percy Crofts Ottley (1885-1917) was born on 31 August 1885 in Ranskill, Nottinghamshire. He was the son of William Henry, a corn merchant, and his wife Jessie Ottley of The Grange, Blyth Road, Ranskill. Percy had an older brother, Ernest, and two younger brothers, Cyril and Stanley.

Educated at Doncaster Grammar School, in civilian life Percy worked as a clerk at Beckett’s Bank in Doncaster. He was a popular local figure, a keen cyclist and bell ringer. Percy was married on 28 September 1909 at St Martin’s Church Womersley, Yorkshire, to Ethel Annie Camm and their daughter Mary was born on 6 December 1910. The family resided at 38 Christchurch Road, Doncaster.

Percy joined the army on 3 February 1916 and trained for a year before being sent to France with 1st/14th (County of London) Battalion, The London Regiment (London Scottish) in August 1917. He had been promoted to lance-corporal on 11 June 1917, but reverted to the rank of private on embarkation in August. His battalion was allotted to 168th Brigade of 56th (London) Division.

Whether Percy Ottley’s death was ‘instantaneous’ is unknown, but officers like Newbiggin usually tried to spare the relatives of deceased soldiers the grim details of men’s deaths when they wrote to them. Instead, they emphasized that their loved ones ‘did not suffer’ or were ‘killed instantly’ in order to provide some small measure of comfort.

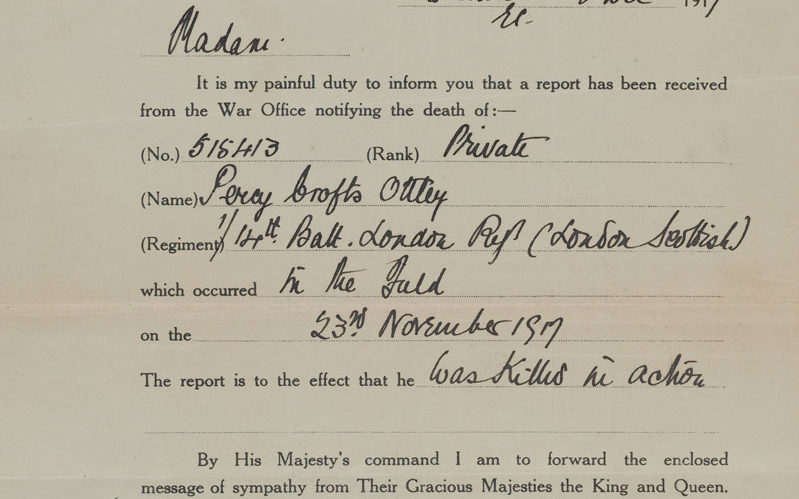

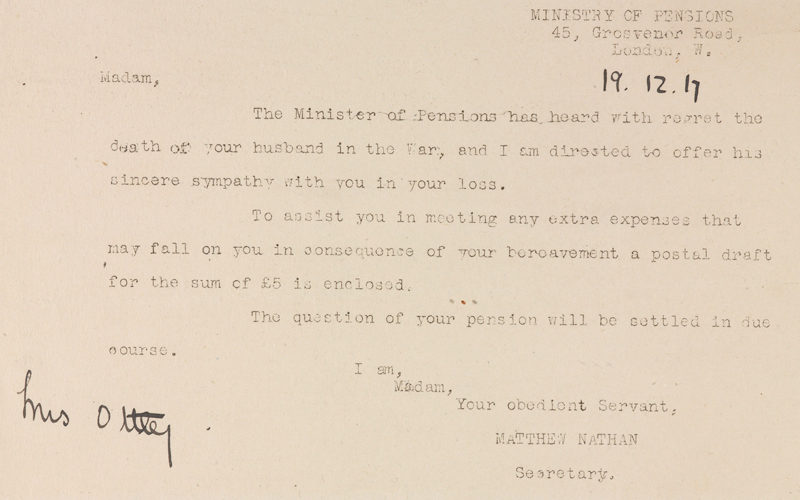

Several items of correspondence in Percy’s collection reveal what happened after a soldier died. Once he was confirmed dead, the next of kin were informed of the terrible news. Officers’ next of kin were informed by telegram. Other ranks’ next of kin were told by receipt of Army Form B104-82. The one sent to Percy’s widow Ethel is displayed here.

More details: NAM. 2004-11-115-6

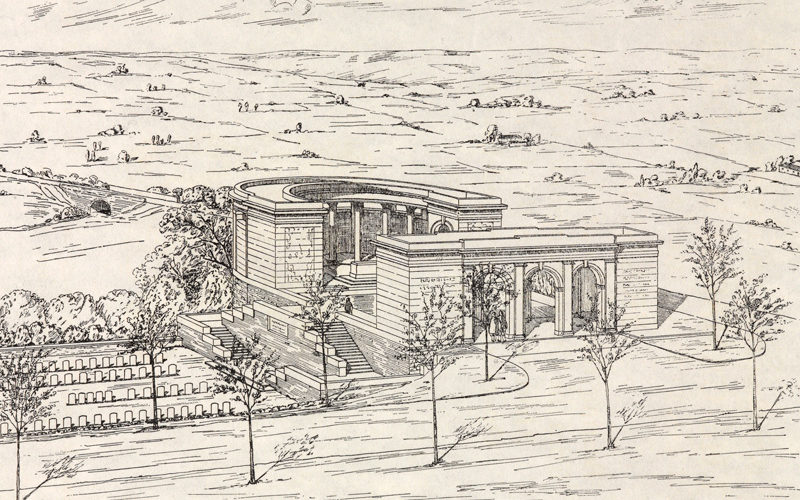

The Graves Registration Units would then inform the next of kin about the place of burial of the soldier. Unfortunately, Percy’s body was never recovered for interment. Instead, his name was listed on the Cambrai Memorial at Louveral along with 7,000 other soldiers from Britain and South Africa who died during the Battle of Cambrai and whose graves are not known.

More details: NAM. 2004-11-115-23

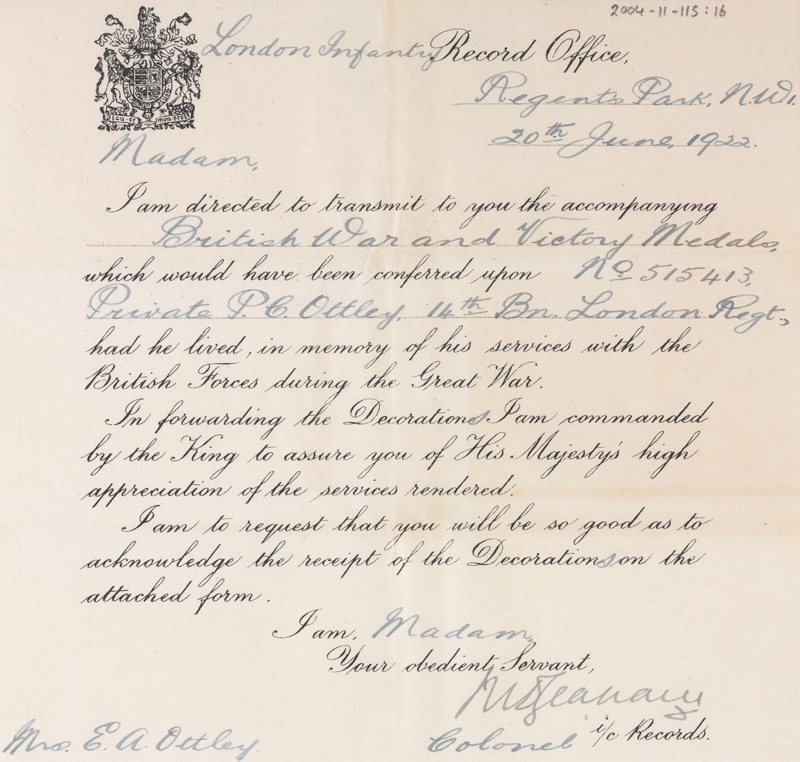

The collection also reveals what measures the government took to assist families left behind after a soldier’s death. The National Army Museum’s Soldiers’ Effects Records show that Mrs Ottley received £5 7 shillings and sixpence from Percy’s back pay and accrued allowances. Other papers show that she then received a weekly pension of 13 shillings and nine pence, a War Gratuity of £3 and information on how to obtain her husband’s campaign medals.

More details: NAM. 2004-11-115-8

Ethel also received a Memorial Plaque (popularly known as the ‘Dead Man’s Penny’), along with a scroll. These were posted to families in 1919-20. Over 1.3 million were sent across the British Empire to commemorate those who had fallen and acknowledge their sacrifice. They were accompanied by a ‘King’s Message’, which contained a facsimile signature of King George V.

As late as 1928, Ethel was still receiving information about plans for the Cambrai Memorial and how she could visit the grave of her husband.

Percy was also commemorated with an alabaster panel at the church of St Mary and Martin in Blyth, Nottinghamshire, and by an inscription on the grave of his grandmother Emma Ottley at St John the Baptist’s Church in Adel, Yorkshire. He is also listed on the London Scottish Memorial at St Columba’s Church in Kensington and Chelsea, and on the memorial at the regimental headquarters at Horseferry Road, Westminster.

Explore further

- Article: Other Soldier Stories

- Article: Battle of Passchendaele

Explore the map for similar stories

Private Percy Ottley - Doncaster, Yorkshire

First World War in Focus

First World War in Focus