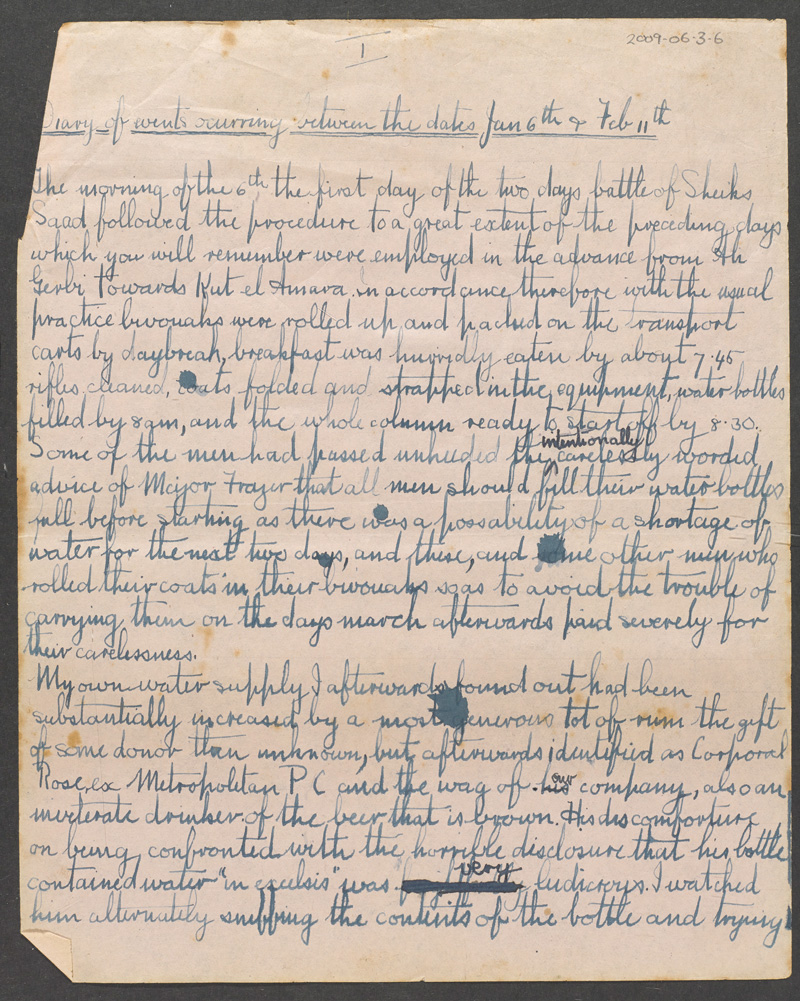

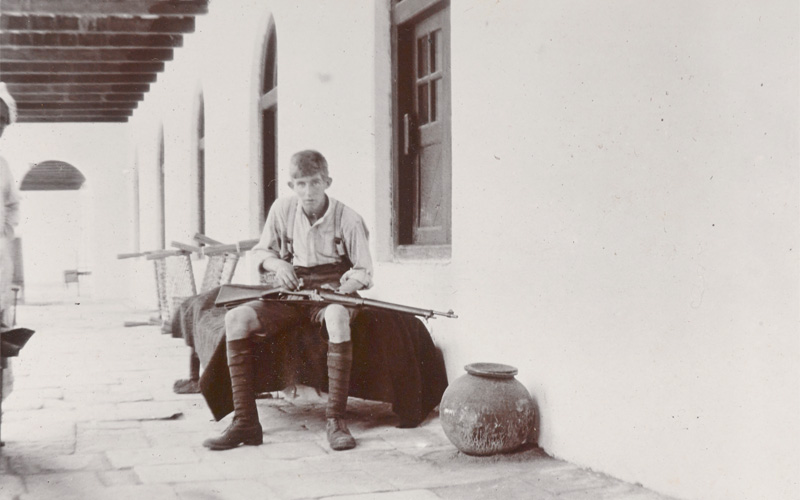

Private William Jay, 1/5th Battalion The Buffs (East Kent Regiment), 1915

More details: NAM. 2009-06-7-1

Private William Jay of 1/5th Battalion The Buffs (East Kent Regiment) provides an eye-witness account of the doomed attempt to relieve the besieged British-Indian forces at Kut.

Attempted relief of Kut

In January 1916 a British-Indian relief force attempted to fight its way through to Major-General Charles Townshend’s besieged division at Kut in Mesopotamia (now Iraq). Townshend’s troops had been surrounded by the Turks since 7 December 1915.

In early January 1916 two Indian divisions, known as the Tigris Corps, were despatched under the command of Lieutenant-General Sir Fenton Aylmer to relieve Townshend’s beleaguered forces. With them was Private William Pryor Jay of 1/5th Battalion The Buffs (East Kent Regiment), part of 35th Brigade in 7th (Meerut) Division. Jay’s diary vividly brings to life the doomed attempt to relieve Kut.

Battle of Shaik Saad

Tigris Corps’ 19,000 troops fought their first major action at Shaik Saad where 22,000 Turks had set up defences astride the River Tigris. Major-General Sir George Younghusband’s 7th Division attacked on both sides of the river – the 35th Brigade on the left bank, the 28th on the right – with a flotilla of gunboats and supply vessels in support.

The assault began at dawn on 6 January. Lacking any elevated ground, effective aerial reconnaissance, or enough cavalry, the attacking troops had to feel their way through mist to discover where enemy positions started or ended. Trying to manage the battle on both sides of the river, Younghusband was unable to control his forces properly. His attack failed with heavy losses on both banks.

Jay wrote in his diary:

‘We were informed by our platoon commander Lieutenant Welldon that we would probably have a scrap as there were three fortified positions to be taken before we reached Kut… I was wondering how I would behave in the coming fight. The fear that one has in battle is negligible compared to the fear of being so afraid that it shows. I am certain of this as both of my friends had exactly the same experience…

‘The mist that had been concealing our presence from the enemy began to rise and shortly afterwards the battle commenced with a single boom from one of our guns on the other side of the river. During the morning we remained on our ground in artillery formation. In our position as support troops we were able to get a splendid view of the day’s fighting. For the first half of the day most of the firing was on the other side of the river from both artillery and infantry. The rattle of rifle fire intensified from minute to minute as the action developed and was punctuated by the regular, heavy boom of the cannon. Far away in the distance our shrapnel and shells were bursting in the air, forming snow white clouds…

‘Suddenly a long drawn out rushing sound is heard terminating in a hollow “clop”, immediately followed by the pleasing spectacle of about 1,000 square yards [836 square metres] of ground being churned up as with a flail. This is our first shrapnel shell… For the next three hours the enemy steadily plastered us with shrapnel, but thanks to our artillery formation, we escape with only five casualties.’

Wounded in action

Aylmer arrived with reinforcements, so another attack was launched the next day. But this too was beaten off. Jay described the fighting:

‘Without any warning we were suddenly told to get out of the trenches and advance… We had advanced a few hundred yards when the long drawn out hiss of bullets passing through us began to be heard and little spurts of earth were sent flying. Almost immediately a man… was struck full in the forehead and fell like a log. The line continued to advance neither quickening nor retarding their pace… One just had time at the end of a rush to sprawl on the ground, get off five rounds, press in a clip of cartridges, shut the bolt, do up your pouch and put up your safety catch before the words “prepare to rush” were heard… Long before the position was reached, however, the fury of the rifle, machine gun and shell fire had become terrific…

‘The hiss of the bullets was continuous and the shells screamed overhead in an ever increasing uproar. Men fell to the ground as they advanced or were left lying still when the line leapt up for the next rush. I turned round and saw a liddite shell fall in the middle of one of our support platoons. Arms and legs and fragments of men were tossed aloft in a swirl of yellow and brown and when the dust had blown away nothing of the platoon remained. The companies advancing behind us were decimated by shell fire. The pandemonium was indescribable. The man next to me in the line had to shout the commands into my ear because I had long since gone stone deaf from the noise. Our rifles were almost red hot and unworkable. Every time I opened my bolt I had to knock it up with my clenched fist and some people could not open their bolts and could no longer fire unless they obtained another rifle from a dead soldier… Perspiration was collecting on my forehead and nose and falling onto my rifle butt and my equipment seemed to have increased in weight. Some fell out of line unhurt but absolutely unable to stay the pace…

‘Enfilading bullets began to hiss more frequently from the enemy’s trenches on our left as we got within the semicircle of their position. Because our native troops had not come up, the Turks’ right flank were able to give us their undivided attention. Our line, the Seaforths and the Black Watch on our right were subjected to raking fire against which it was impossible to reply. We noticed broad bands of whitewash painted on the ground and wondered what they were. We were soon to know when the first platoon crossed one of them and lost a third of their men by machine gun fire…

‘I was firing about my 81st round and just lowering my rifle when “smack” a stinging numbing sensation occurred in my right forearm rendering it useless.’

Terror stricken

As the battle raged on, Jay made his way back to British lines:

‘In order to minimise the chances of being hit I decided to build a bullet proof parapet in front of me. I managed to get out the handle of my trenching tool but could not get the tool itself out of the carrier with only one hand, and had to give up the attempt. Whilst moving my arm I realised that it was bleeding profusely…

‘After this I lay perfectly still with my face pressed on the ground and prayed for darkness to come quickly. About half an hour later something occurred that filled me with fear… Above the sound of the bullets I heard the high-pitched drone of a machine gun… the gunner was spraying my position with bullets…

‘I buried my face in the ground. I was too paralysed to think, all my manhood oozed away, I was a terror stricken little child. I suppose that it lasted for about a minute and then the monotonous drone of rifle bullets recommenced. When my mind started to return to normal I realised that the fire had lessened and I saw a wounded Highlander hobbling back towards the dressing trench. I decided to make a similar move myself and had made about 30 yards [27m] when a circle of little puffs of dirt thrown into the air in front gave me warning that I was a target again. After a rest on the ground I set off and this time made 150 yards [137m] before snipers spotted me once more, making further progress impossible…

‘I decided to give them the satisfaction of thinking they had “got me” so I flopped down as much like a mortally wounded man as I could manage and slid into a nice burrow. Immediately the snipers stopped firing… Taking advantage of my good fortune I rested for half an hour before proceeding to the dressing trench.’

Turkish withdrawal

Attacking again during the night of 8-9 January, the British were then surprised to discover the Turkish trenches unoccupied. Jay heard the sound of cannon getting fainter, which he took to mean that the enemy was retreating.

‘Later we heard that the 4th and 5th Hants on the other side of the river had attacked the extreme right of the enemy position, and by an outflanking movement, had caused them to evacuate their position on the right side of the river. This exposed the flank on our side of the river and compelled the entire Turkish force to withdraw.’

In fact, the Turks had withdrawn overnight, perhaps overestimating British strength. Their commander, Nur-ud-Din, could not justify this decision to his superiors and was summarily dismissed.

No relief for Kut

Aylmer pushed on and rapidly reached Hanna, about 16km (10 miles) from Kut. However, he was unable to break through the Turkish defences during the Battle of Wadi and the Battle of Hanna between 13 and 21 January 1916.

Further attacks by the relief force in March and April all failed with heavy losses. The starving Kut garrison was eventually forced to surrender on 29 April 1916. Tigris Corps retreated to Basra, where the British spent the remainder of the year rebuilding their forces.

A horrible state of affairs

The relief forces’ medical arrangements were completely inadequate, made worse by rain and the muddy conditions it caused. Provision had been made to handle 250 casualties, but by the end of 9 January there were 4,000 in Tigris Corps. Some of the wounded had to wait ten days before they were assessed at field ambulances and sent to hospitals at Basra.

Jay describes the appalling conditions and lack of care suffered by these wounded men as they waited to be transported downriver:

‘Every square foot of the 25 tents was occupied by the wounded with many also lying on stretchers outside the tents or sitting propped up against the canvas tent walls. I saw at once that it would be impossible for me to get inside any tent and I resigned myself to spending the night in the open air…

‘A long procession of transport carts brought in wounded from the firing line three miles away. As these carts were without springs and the country full of ruts and bumps, the plight of these soldiers was pitiable in the extreme. Many died from loss of blood occasioned by the jolting of the carts…

‘There was a complete dearth of stretchers because the men already in the hospital had been allowed to remain on those to avoid contact with the rain sodden ground. The fortitude with which these unfortunate men endured their tortures was remarkable; only one or two allowed so much as a groan to issue from their tightly closed lips. I shall never forget the spectacle… It was getting very cold. Freezing wind laden with sleet had sprung up rendering our position untenable and sleep out of the question. In addition my wounded arm had gone very cold and pained me terribly…

‘Very soon I forgot my own troubles in the scene of carnage around me… Hundreds of men shot and maimed in every conceivable portion of their bodies, lay helplessly on the ground around me. Here a native soldier, his brains protruding where a shell splinter had torn away the protecting skull, lay deep in a coma. Next to him his white brother shot through the stomach was sipping hot condensed milk and water that an orderly was holding to his lips. There a human being rent and mangled, dyed yellow by the liddite of a high explosive shell, showed by his rigid limbs and glazed eyes that death had released him from his agony. The smell of blood mingled with the first dressings was a very sickening odour…

‘It is almost impossible to describe the state of confusion that existed in the field hospital. Wounded men covered not only the area of the hospital but a considerable amount of the adjoining ground. Attending them were two European and three native doctors and half a dozen orderlies. The unfortunate, overworked doctors were working every hour of the night hurrying from one case to another, but still only finding the time to attend the most seriously wounded… Poor Dr Collinridge is reported to have broken down on the third day after Shaik Saad and wept like a child. Well he might, for he had been working day and night for three days without any sleep or respite…

‘I shall never forget my disgust and horror at finding myself crawling with loathsome insects; the bedding they gave us was verminous. The foul brood even invaded my dressings and penetrated my gaping wound. I was unable to rid myself of them until I reached Basra hospital, where my clothes, filthy with dirt and blood, were destroyed in an incinerator…

‘The lack of hygiene led to an outbreak of dysentery which affected about one in four men. A more horrible state of affairs can hardly be imagined as some of the wounded men could not move quickly enough… The only redeeming feature of this awful state of affairs was the mutual charity and good will that existed among the wounded. Everybody in my tent did their utmost to assist any of their comrades who were unable to look after themselves.’

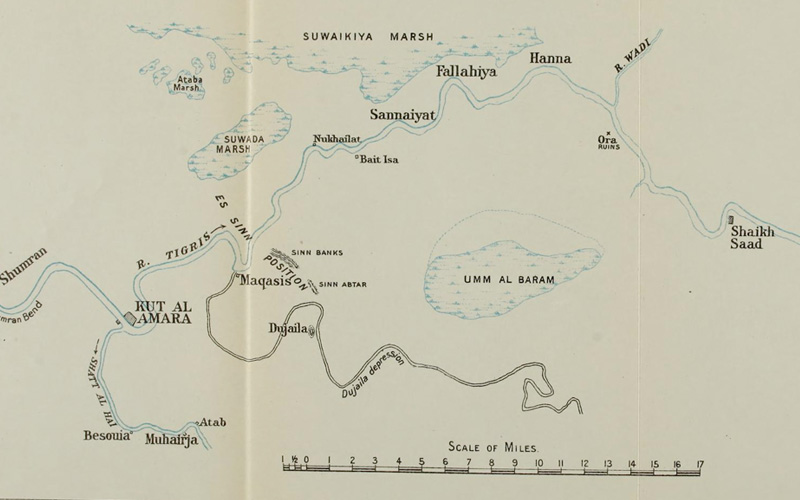

Map of the River Tigris between Kut and Shaik Saad

Published in The Campaign in Mesopotamia, 1914-1918 (vol 2) by FJ Moberly, 1924

Biography

William Pryor Jay (1893-1917) was born in 1893 at Wimbledon in Surrey, the son of Pryor Jay, a draper, and his American wife, Helen Phoebe Jay (nee Van Gaasbeek). His father had lived in the United States for a few years, but returned to Britain in 1889.

William had three older sisters, Phoebe, Carrie and Grace. He was educated at the King’s College School, Wimbledon. In 1900 the family resided at 15 Park Road, Wimbledon, but by 1909 they had moved to Murray Lodge on Murray Road, also in Wimbledon.

After leaving school, William worked in his father’s shop on Regent Street. In August 1909 he attended Officers’ Training Corps at Farnborough Common. The following year he began studying at Wye Agricultural College in Kent.

William Jay enlisted in August 1914 along with his fellow Wye students at Ashford in Kent with 1/5th (Weald of Kent) Battalion The Buffs (East Kent Regiment). He was then living with his family in Staplehurst. Following mobilisation, his battalion was sent to India on 29 October 1914 on board the SS ‘Corsican’.

Initially posted to 5th (Mhow) Division, Jay was briefly hospitalised with illness at Kamptee. In November 1915 his battalion transferred to 35th Brigade in 7th (Meerut) Division after landing at Basra.

Following the Battle of Shaik Saad, Jay was sent back to Basra and the bullet lodged in his arm was eventually removed. After recovering, he re-joined his unit which moved to the newly-formed 14th (Indian) Division in May 1916 and continued to serve in Mesopotamia.

It took part in the renewed advance on Baghdad, launched on 13 December 1916, under Lieutenant-General Frederick Stanley Maude. Unlike his predecessors, Maude was a methodical and talented leader whose force was boosted by increased artillery and improved logistical, medical and transport support.

Jay was killed in action at Dahra Bend on 15 February 1917. Kut fell eight days later and Baghdad was occupied on 11 March. William Jay was initially buried at Bassonia, just south of Kut, but later interred at Amara War Cemetery, further down the River Tigris. His effects were sent to his parents at 55 Seddlescombe Road South, St Leonards-on-Sea, Sussex.

Explore

- Article: Other Soldier Stories

Explore the map for similar stories

Private William Jay - Wimbledon, Surrey

First World War in Focus

First World War in Focus