Letters written by Regimental Sergeant Major Arthur Harrington of 5th (City of London) Battalion, The London Regiment (London Rifle Brigade) reveal the excitement, uncertainty and fear felt by soldiers following the outbreak of war.

The Army on the eve of war

Britain went to war in 1914 with a small, professional army that was primarily designed to police its overseas Empire. The entire force consisted of just over 250,000 Regulars, which, together with 250,000 Territorials and 200,000 Reservists, made a total of about 700,000 trained soldiers. This was tiny when compared to the mass conscript armies of Germany, France and Russia.

Although small, the Regular Army of 1914 had learned from the harsh lessons of the Boer War (1899-1902). Reforms in training had been introduced which meant that, man-for-man, the soldiers of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) were among the best in Europe.

Each Regular Army regiment and corps had locally recruited Territorial Force (TF) units attached to it. Men trained during the evening, at weekends and at summer camp. In the event of war they could be called upon for full-time service. Territorials were not obliged to serve overseas, but when asked in August 1914, the vast majority agreed to do so.

There was also the Special Reserve (SR), whose men enlisted for six years and could be called up in the event of general mobilisation. Their period as a Special Reservist started with six months full-time training, followed thereafter by four weeks training per year. There were over 100 Reserve battalions in August 1914. They went on to provide reinforcement drafts for the active service battalions on the Continent.

While many expected the war to be ‘over by Christmas’, the Secretary of State for War, Field Marshal Lord Kitchener, realised the conflict would be long and on an unprecedented scale. Britain would have to create a mass army for the first time. He therefore appealed for volunteers for his ‘New Armies’ in August 1914.

These volunteers enlisted ‘for the duration of the war’. They had a choice over which unit they joined, but had to meet the same age and physical criteria as the Regulars. Men who had previously served in the Army were accepted up to the age of 45. Despite the regulations, many underage and overage men enlisted.

Often they joined ‘Pals’ battalions, organised on a local basis. The advantage of this was that the new battalions came with existing ties, which the Army could develop. The disadvantage was that if a unit suffered heavy casualties it could have a devastating effect upon a community.

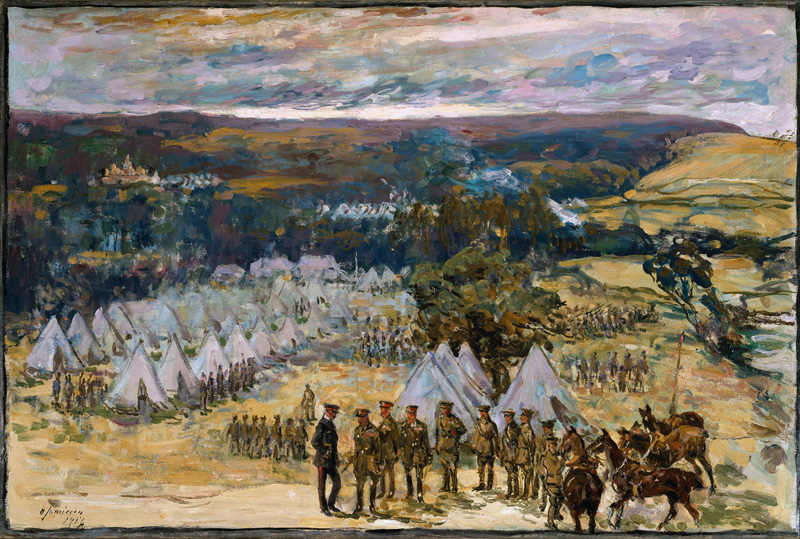

The thousands of eager volunteers who flocked to the Colours on the outbreak of war were completely untrained. They spent their first months in the Army learning the basics of soldiering. Drill, skill-at-arms and manoeuvres were learnt at huge camps situated all over the country.

‘The greatest battle in the history of the world’

The ‘New Armies’ would face their baptism of fire in the battles of 1915-16. Until then, the Regulars, supported by the TF and SR, would take the leading role. Among their number was Regimental Sergeant Major Arthur Harrington of 5th (City of London) Battalion, The London Regiment (London Rifle Brigade). The letters he wrote to his wife during this period give us an insight into the excitement, uncertainty and fear felt by soldiers following the outbreak of war.

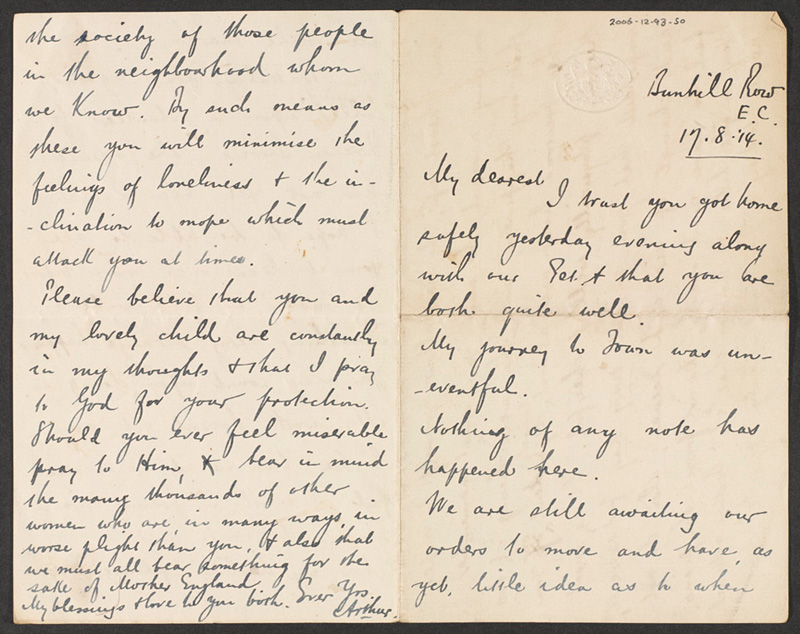

Re-called to his unit at 130 Bunhill Row in the City, he wrote on 13 August:

‘It is pretty certain that we shall not be allowed home as before… Everything is going very well but of course I am slogging 12 hours a day and will have to do so for a while… It looks as if the greatest battle in the history of the world will soon be in progress.’

Four days later he continued:

‘We are still awaiting our orders to move and have as yet, little idea as to when we shall march. The battalion was again called upon for foreign service. The result has not yet been published. I hope to be able to see you at least once more before we move… My work doesn’t get any lighter but as it is successful I must, in present circumstances, be quite content. Now, my darling, please keep the society of those people in the neighbourhood whom we know. By such means as these you will minimise the feelings of loneliness and the inclination to mope… Please believe that you and my lovely child are constantly in my thoughts and that I pray to God for your protection. Should you ever feel miserable pray to him and bear in mind the many thousands of other women who, are in many ways, in a worse plight than you, and also that we must all bear something for the sake of Mother England.’

Several of his letters dwell on financial concerns, such as when his wife would receive her separation allowance. This was a portion of a soldier’s pay which was matched by the government and sent to his dependents to make sure they were not left destitute. Other letters reveal how their extended family had offered to assist them in Arthur’s absence.

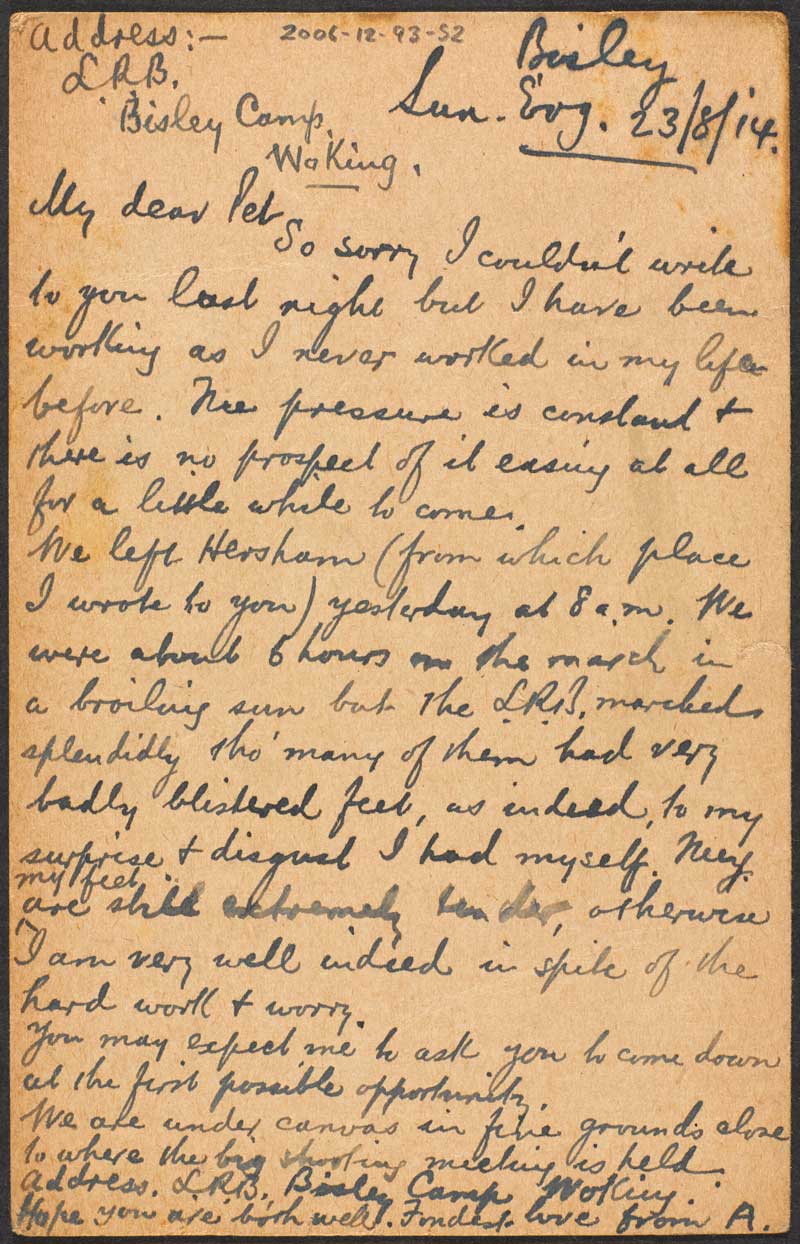

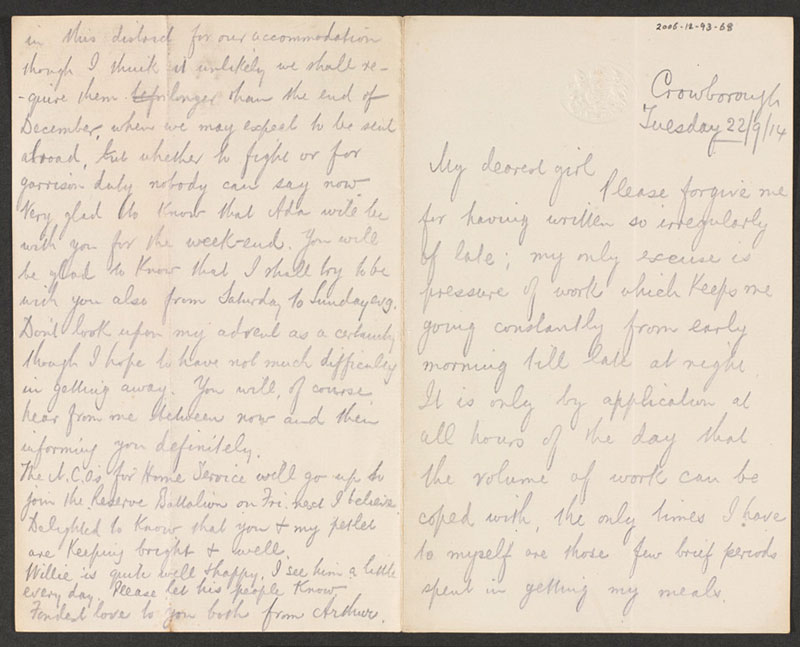

Eventually, Harrington was mobilised with 2nd Brigade of 1st Division, and moved on to Bisley and Crowborough camps where he helped train his part-time soldiers:

‘I have been working as I never worked in my life before. The pressure is constant and there is no prospect of it easing at all for a while to come. Yesterday we were about 6 hours on the march in a broiling sun but the LRB [London Rifle Brigade] marches splendidly though many of them had badly blistered feet, as indeed, to my surprise and disgust I had myself… We are under canvas in fine grounds close to where the big shooting meeting is held… My work continues to keep me busy from 6am to 9pm with short intervals for meals, but everybody else is working hard too and I am feeling exceedingly well, and enjoying the long hours in the open air… I feel awfully relieved to read in your letters that you and our pet are keeping well. I should worry so much if either of you was unwell… As to our meeting it would be impossible for one to go away from here unless under exceptional circumstances… We haven’t the slightest idea what the future holds for us yet but we are likely to be in uniform for at least a few months.’

The following week, Arthur was lucky enough to meet his wife and daughter when they visited Bisley:

‘It gave me great pleasure yesterday to see you and our little darling looking so well as you did… We must be thankful for the happy reunion and await another opportunity… It seems to be generally thought that we shall be sent to Malta but nothing is certain as to that or where we are to go but it cannot be long deferred as the cold weather will be upon us in a few weeks… For preference I would much rather go to Egypt or South Africa but we have no choice.’

He believed that the unit would be sent abroad in December, ‘but whether to fight or for garrison duty nobody can say now’. Although the tented accommodation was basic and the training regimes at Bisley and Crowborough hard, Harrington thought the food ration ‘quite a liberal one consisting of bread, meat, cheese, bacon, jam, tea, sugar’. More importantly, his men were ‘in fine spirit and are in general very bright and happy’.

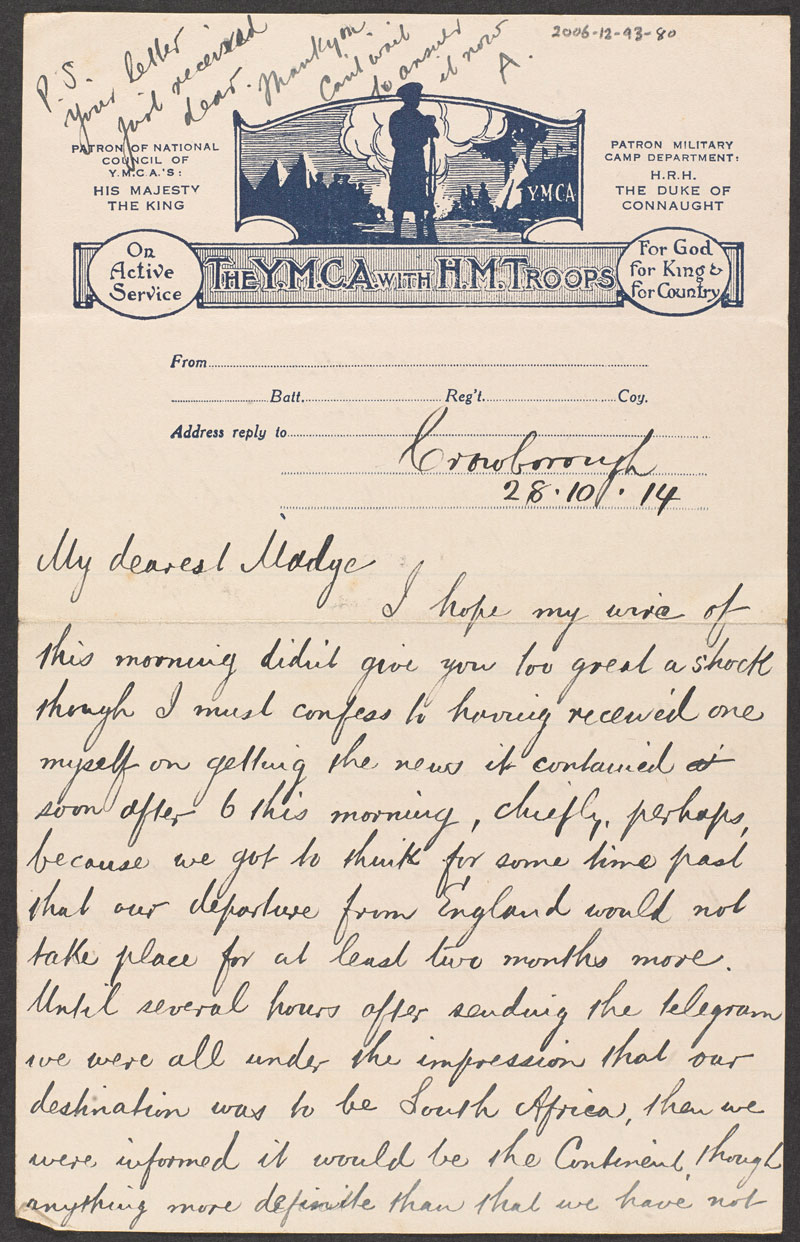

In late October Harrington wrote to his wife with news of their imminent departure abroad.

‘We were all under the impression that our destination was to be South Africa, then we were informed it would be the Continent though anything more definite than that we have not yet been told. Now my dear love, do not be at all alarmed or depressed because I am to go across the Channel. It seems to me that we shall not be sent anywhere near any fighting but be employed in guarding lines of communication in rear of the Regular Army. It isn’t in the least likely that these indifferently trained Territorial Battalions, armed with a rifle they know nothing about as yet (we are to get a new rifle) will be thrown into the fighting line. Thousands of men will be needed to guard railways and that is going to be our job I feel convinced. However, come what may I must try to do my duty to my country in the way it wants me and you yours by bearing-up and being as cheerful as you can so that I may not be worried by supposing that you cannot be a brave girl, though I know you to be that and more.’

Arthur’s unit eventually landed at Le Havre in France on 17 November 1914 and went into the line with 11th Brigade of 4th Division. They were used as reinforcements for the hard-pressed BEF, so Arthur was wrong in his belief that the Territorials would not see action.

Another of his letters, sent prior to his departure, reveals that his wife was pregnant with their second child. This daughter, named Joan, was born on 15 April 1915. Unfortunately, Arthur never got to see her. He was killed on 28 April by a shell blast while having his breakfast in a farmhouse at St Jean during the Second Battle of Ypres (22 April – 25 May 1915).

Biography

Arthur George Harrington (1869-1915) was born in St Thomas Parish Winchester, the son of John William Harrington and his wife Ellen. His father was a soldier and Arthur and his five brothers grew up at several military establishments including Anglesea Barracks at Portsea.

Following in his father’s footsteps, he joined 1st Battalion The Lincoln Regiment on 22 November 1892, but transferred to 3rd Battalion The King’s Royal Rifle Corps (KRRC) on 10 October 1894 to serve with his elder brother.

Harrington served in Egypt and India and by March 1898 had been promoted to sergeant. He then fought in the Boer War (1899-1902) where he was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM). He was made a colour sergeant in November 1903.

After many years of Regular service, Harrington was eventually posted to the 9th Volunteer Battalion of the KRRC (later re-named 5th Battalion The London Regiment), where he became responsible for training its Territorial soldiers. By 1914 he and his wife Florence Margaret were living with their daughter Margaret at 47 Westbury Road, Bowes Park in London and he had reached the rank of regimental sergeant-major.

Harrington’s body was never recovered, but his name was later listed on the Menin Gate Memorial at Ypres.

Explore

- Article: Other Soldier Stories

Explore the map for similar stories

Regimental Sergeant Major Arthur Harrington - Winchester, Hampshire

First World War in Focus

First World War in Focus