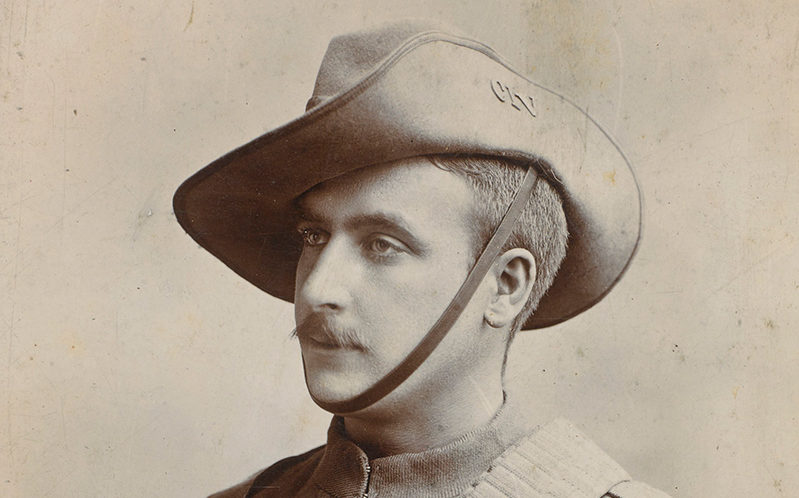

Sergeant Samuel Pye of the City of London Imperial Volunteers, 1900

More details: NAM. 2002-11-656-3

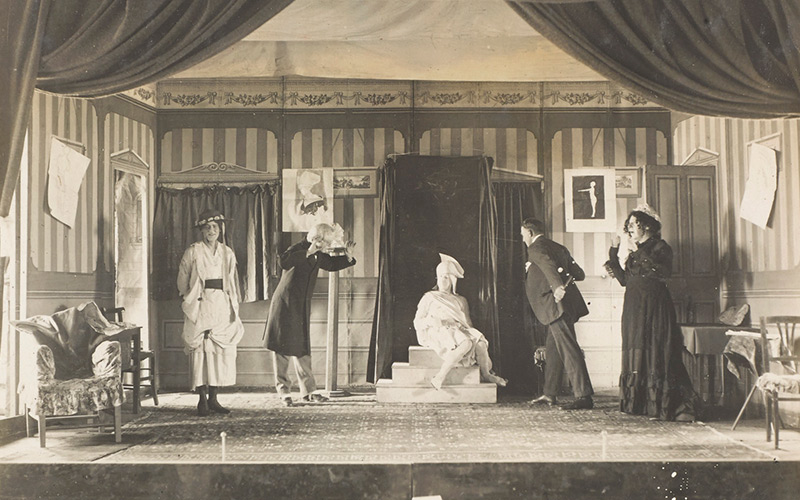

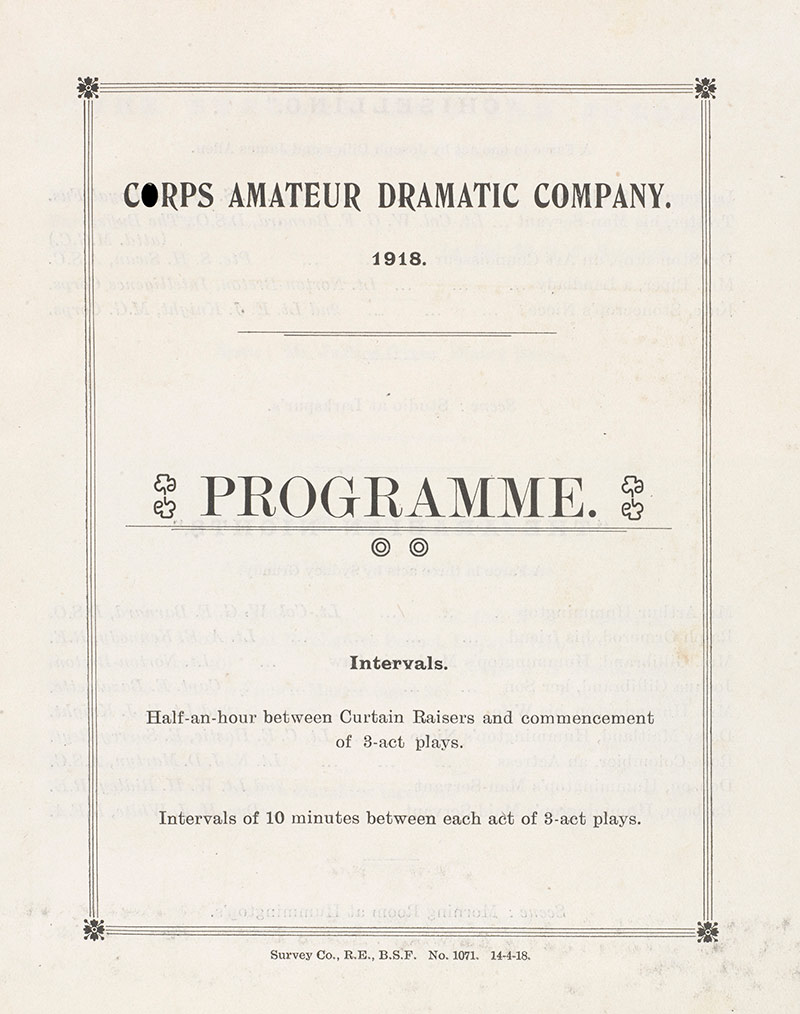

Between February and April 1918, Battery Quartermaster Sergeant Samuel Pye took a series of photographs of British soldiers from XVI Corps staging concert parties to boost morale. His album shows us that soldiers’ lives on the Western Front were not always about death and destruction. Even amid the horrors of war they could still have fun.

Front, support and reserve

Soldiers did not spend their whole time in the front line. While one unit was at the front, others would be in support in case of attack, or out of the line entirely, resting and training in the rear areas.

A typical infantry soldier was only in the front line trenches for about a third of his total time overseas. Normally he would spend four days in the front line, then four days in reserve and finally four at rest, although this often varied depending on local conditions.

Training and cleaning

Once out of the line, soldiers attended lectures, drilled, cleaned kit, washed and de-loused themselves and their uniforms. They were put to work repairing roads, building camps and digging new trenches. It was also a chance to give the troops medical treatment where it was needed.

Soldiers outside the divisional baths on the Arras road near St Pol, 1917

More details: NAM. 1978-11-157-24-18

Entertainment

Libraries, canteens, churches, social clubs, baths and concerts and many other facilities were established in the rear areas so soldiers could relax. The Army ran most of these, but charities, volunteers and religious groups operated others. Units also organised their own entertainments – as was the case with Pye’s XVI Corps.

Distraction

Such entertainment was organised to break up the monotony of Army life and provide a distraction from the horrors of war. It also kept soldiers occupied and out of trouble when not on duty. Indeed, commanding officers were always concerned about keeping men away from the tavern, brothel and bookmaker.

Activities like concerts and sports helped reinforce group identity and made soldiers ready to serve a common cause. They also bridged the gap between officers and men, who often had little else in common.

Concert party

One of the most popular pastimes was the concert party. Sometimes these featured professional artists, but more often included serving soldiers. Some talented soldiers were lucky enough to be released from their units to work full-time in official military concert parties formed by the Army to entertain its men.

Other concerts were ad hoc affairs belonging to Britain’s rich amateur dramatics and music hall traditions. Usually a divisional or corps concert troupe drew its men from different regiments. Pye’s album depicts officers and men from many of the XVI Corps’ units. By 1917, each division had at least one military theatre company.

Casting

The assembling of a cast was a constant problem, and it was difficult to maintain a permanent staff due to the movement of units or cast members being killed or wounded in action. The list of actors and staff for each show photographed in Pye’s album continuously changes over the three-month period it covers.

Songs

The concerts usually featured soldiers as singers, actors, comedians and female impersonators. The selection of songs was important, and the most popular ones were those in which the troops had the opportunity to join in the chorus. Singing was a good way of releasing tension.

A scene from ‘Arabian Nights’, featuring Lieutenant E Knight as ‘Mrs Hummingtop’, 1918

More details: NAM. 2002-11-650-11

Drag acts

These always proved popular with the men and have been a much-studied phenomenon. Some historians argue that cross-dressing represented a humorous rejection of traditional male gender roles. Others maintain that the man in drag served as a surrogate woman for soldier audiences pining for sweethearts at home, or even allowed some troops to engage in homo-eroticism.

Some soldiers seem to have specialised as female impersonators. In Pye’s album Lieutenant E Knight regularly appears as a woman in various productions.

A scene from ‘Chiselling’, featuring Lieutenant E Knight as ‘Kate’, 1918

More details: NAM. 2002-11-650-5

Morale boost

The shows were usually held in makeshift venues and featured props and costumes made from discarded materials. The concerts were usually free for soldiers, and their laughter, humour, pranks, and songs helped them to endure life at the front.

They also gave the cast a platform on which to air grievances about food, conditions and senior officers; thus providing something of a safety outlet for frustration within the British Army.

More details: NAM. 2002-11-650-14

Some soldier-made shows became so successful that they left the Western Front and entertained audiences at home. ‘The Dumbells’ of the Canadian Army even managed a run in London’s West End. Most of the soldiers’ concert parties were less sophisticated and remained at the front, but they nevertheless greatly boosted morale.

More details: NAM. 2002-11-650-15

Biography

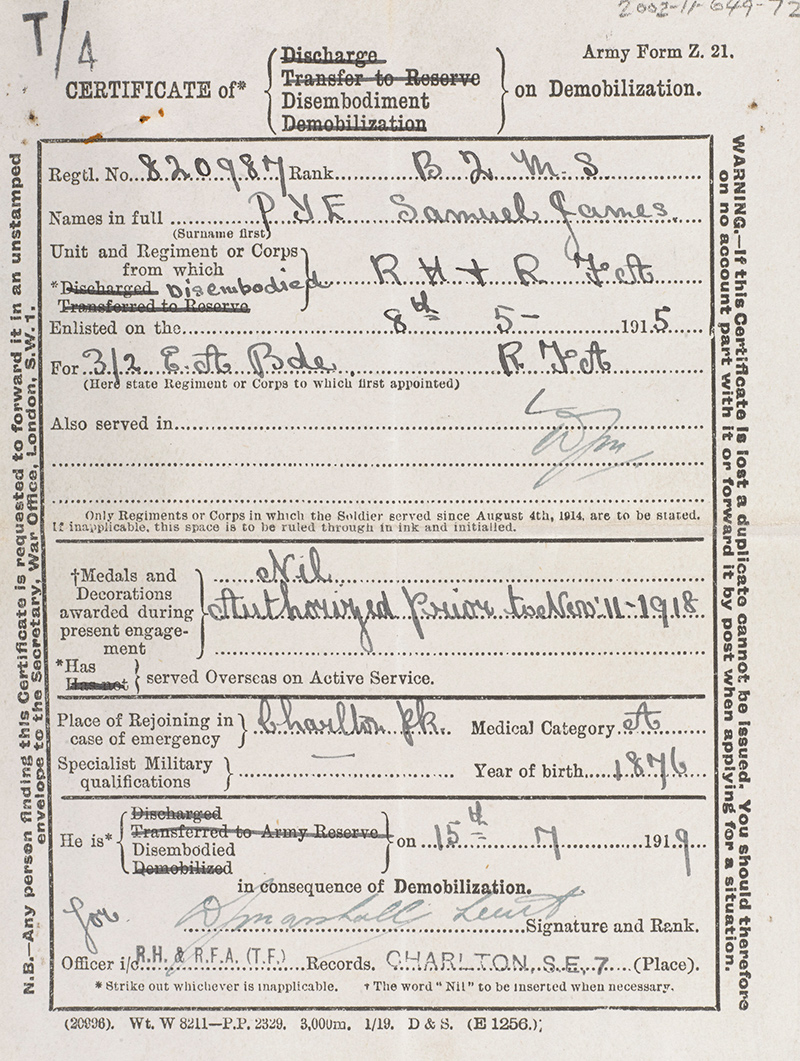

Samuel James Pye (1876-1939) was born on 4 August 1876 at Old Ford in Bow, London. He was the son of Samuel Pye who was a builder. Samuel was educated at Olga Street School in Tower Hamlets, London. After his education he worked as an advertising clerk in the City.

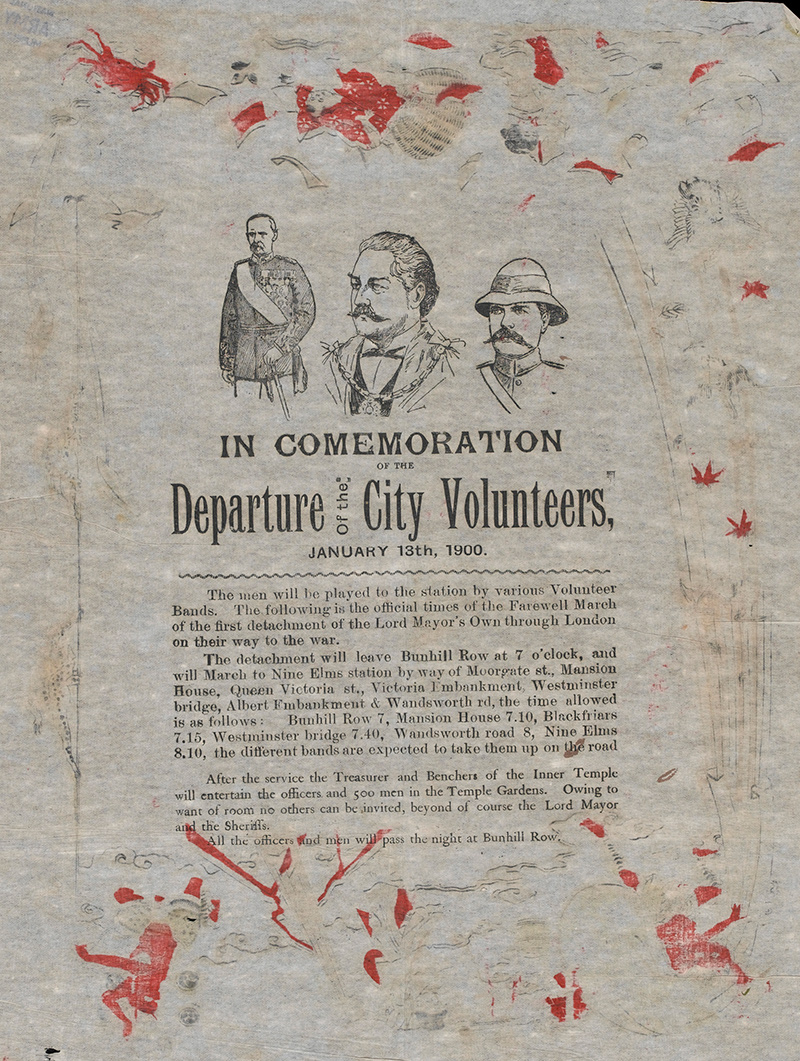

Pye enlisted with the 1st Essex Royal Garrison Artillery Volunteers on 13 November 1892. This was based at Barking in Essex. The need for trained men to fight in the Boer War (1899-1902) led to an appeal in January 1900 for men serving in the volunteer units in the London area to join the City of London Imperial Volunteers.

This unit was raised in December 1899 by the Lord Mayor of London and equipped at the expense of the City Corporation. It eventually comprised two companies of mounted infantry, one battalion of infantry and one battery of artillery.

Private Pye attested at the Guildhall on 4 January 1900 and left Southampton with 16 other comrades from the Essex Volunteer Artillery on 27 January aboard the ‘Pembroke Castle’ troop ship. He fought in South Africa until November 1900.

On his returned to Britain, Pye was made a Freeman of the City of London for his services. He was discharged from the City Imperial Volunteers on 30 November 1900 following their disbandment, but remained with the 1st Essex Volunteers until March 1908.

He married Beatrice Sarah Eleanor Kinch on 2 June 1901 at St Leonard St Mary, Tower Hamlets. He was then residing at 61 St James Road, Stratford. The couple had two children, Samuel Arthur Ramford (born 1902) and Beatrice Emily Jane (born 1910). From 1911 the Pye family lived at 2 Holness Road in Stratford.

Pye re-enlisted in May 1915 and served with the 59th Divisional Ammunition Column, Royal Field Artillery (TF). The 59th was a second line Territorial formation raised in January 1915. After training, it served in Ireland during the Easter Rising (1916) and deployed to the Western Front in the spring of 1917. It went on to fight at the Third Battle of Ypres (1917) and at Cambrai (1917), but suffered heavy losses during the German Spring Offensive (1918).

In May 1918, the shattered 59th Division was temporarily disbanded and its battalions reduced to training cadres, the surplus men being drafted to other units. However, the divisional artillery remained in the line, serving with the 62nd, 37th, 5th and 61st Divisions for the remainder of the war.

Pye survived the 1918 battles and was discharged from the service at Charlton on 15 July 1919. For his wartime contribution he was awarded the Meritorious Service Medal.

In later life he lived with his family in Stratford. He died on 9 November 1939 at Queen Mary’s Hospital, Stratford.

Explore further

- Article: Other Soldier Stories

- Article: Easter Rising

- Article: Third Battle of Ypres

- Article: Cambrai

- Article: German Spring Offensive

Explore the map for similar stories

Battery Quartermaster Sergeant Samuel Pye - Old Ford, London

First World War in Focus

First World War in Focus