Florence Simpson was Chief Controller of the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps at the end of the First World War. Her visit to France in December 1916 played an important part in establishing the first uniformed military service for women, and formalising their work in non-combat army roles.

Early life

Florence Edith Victoria Simpson, née Way, was born in St Peter, Jersey on 9 October 1874. She was the eldest child of Colonel Wilfred Fitz Alan Way and Henrietta Maria Ross, and had three sisters – Ethel, Violet and Daisy – and a brother, Wilfred. During Florence’s childhood, the family lived in Southsea, Hampshire.

On 3 December 1895, aged 21, she married Lieutenant Henry Edmund Burleigh Leach. Henry, like her father, was an officer in the Northumberland Fusiliers, and served in the Boer War of 1899-1902. Florence followed Henry to many of his military postings, living with him in Gibraltar between 1905 and 1910 while he served as military secretary to the governor. The couple moved to Gillingham, Kent, on their return to England.

In August 1914, Henry went into action in France. He was badly wounded in October and returned home. For the rest of the war he worked at the War Office.

The Women’s Legion

By 1915, the British Army was concerned about how to cater for its troops. Food was a precious resource, but it was being wasted through poor preparation, or being cooked so horribly the soldiers refused to eat it. Lady Londonderry proposed the creation of a women’s unit to cook for the Army. It was sanctioned by the Army Council in August 1915 and based in Dartford.

The new cookery section, known as the Women’s Legion, was entirely voluntary, but adopted a military style of management. Volunteers wore uniform and were recruited through the local labour exchange for cooking, gardening and motor driving jobs. Florence quickly volunteered to help.

Some of the women with professional experience looked down on rich socialites who thought it fashionable to do their bit. Lillian Barker, Chief of the Women’s Cookery section and a former principal of a women’s correctional facility, believed this to be the case when Florence arrived at her office. Barker sent the ‘vision of radiant beauty’ away to the labour exchange, thinking that she would not see her again. Florence returned within the hour.

She was made Head Cook at Summerdown convalescent camp in Eastbourne shortly after. By the end of 1915 she had succeeded Barker as Commandant of Cooks in the Women’s Legion.

The Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps

1916 had proved a costly year for the British Army. Huge losses on the Somme meant there were fewer men available to fight. At the same time, plenty of able-bodied soldiers were tied up in various non-combat roles.

Although the government had introduced conscription in an earlier response to the manpower crisis, they now began to investigate how women could be employed by the Army to replace men in auxiliary jobs.

Meanwhile, Florence had shaped the Women’s Legion into a more business-like organisation. Using her husband’s influence in the War Office, she worked to promote the organisation’s interests and persuade the Army of the Women’s Legion’s capability for service abroad. There was a rule that women were not to be allowed within three miles of the trenches, but Florence planned a trip to France all the same.

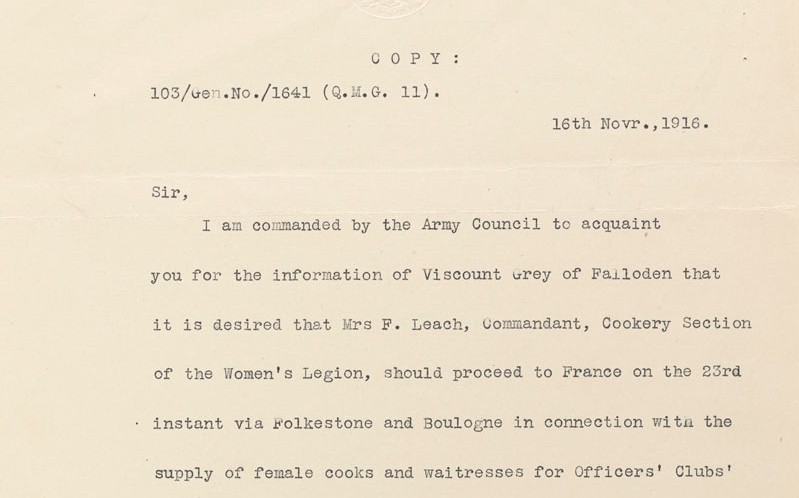

Planning for the trip took place in mid-November 1916. Letters in Florence’s collection show that the Quartermaster General’s Office (which oversaw supplies for the whole Army) and the Foreign Secretary assisted her in obtaining passage to France.

More details: NAM. 1998-01-78-2

Florence travelled to France on 4 December 1916. She investigated how women could work with the Army, and whether the Women’s Legion could take over the running of officers’ clubs from the Army Service Corps.

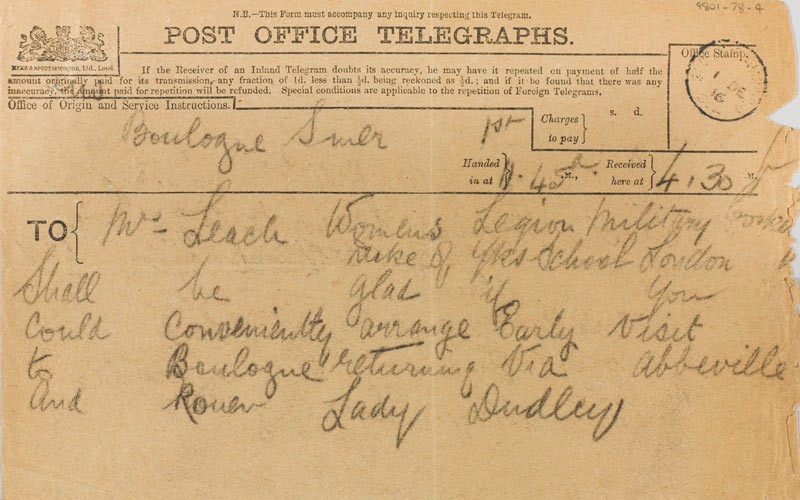

Lady Rachel Dudley, Superintendent of Officer’s Clubs and Rest Houses (who had herself created an Australian military hospital on the Western Front in 1914) took an interest in Florence’s visit. On 1 December, Lady Dudley sent her a telegram: ‘Shall be glad if you could conveniently arrange early visit to Boulogne…’

Telegram from Lady Rachel Dudley to Florence Leach regarding her visit to France, 1 December 1916

More details: NAM. 1998-01-78-4

At the same time, the Army Council decided to give proper consideration to the subject of women’s labour. On the same day that Florence departed for France, the Adjutant General Neville Macready wrote to British Expeditionary Force (BEF) commander General Sir Douglas Haig seeking his thoughts on using women in military roles. Haig was hesitant but eventually agreed because of his concern that a lack of manpower could cause serious problems for his battle plans in 1917.

The Women’s Committee, established in November 1916, also delivered their report on women’s work to the Army Council. It argued for the employment of women in war services, and a centralised co-ordination of women’s organisations.

Two days later, on 16 December, Lieutenant General Henry Merrick Lawson travelled to France to survey how manpower was being used. On 20 December 1916, Macready wrote to John Cowans, the Quartermaster General, that decisions needed to be made about women’s service. He explained:

‘The time has arrived when there should be some small central body in the War Office to deal with the whole question of women labour employed by the army in any capacity whatever. I see no reason why the women should not be organised in units and formations, and from that point of view I should be prepared to take it up. A small Committee of three or four, certainly no more than four, composed say of two men and two women, should be formed in the War Office to deal with the whole question.’

Women for service at the front

Following Macready’s letter, the War Office held a conference to consider women’s war work. On 5 January 1917, Florence (the only woman in attendance) agreed that ‘women were anxious to be under every sort of army discipline, and to take the place of soldiers’.

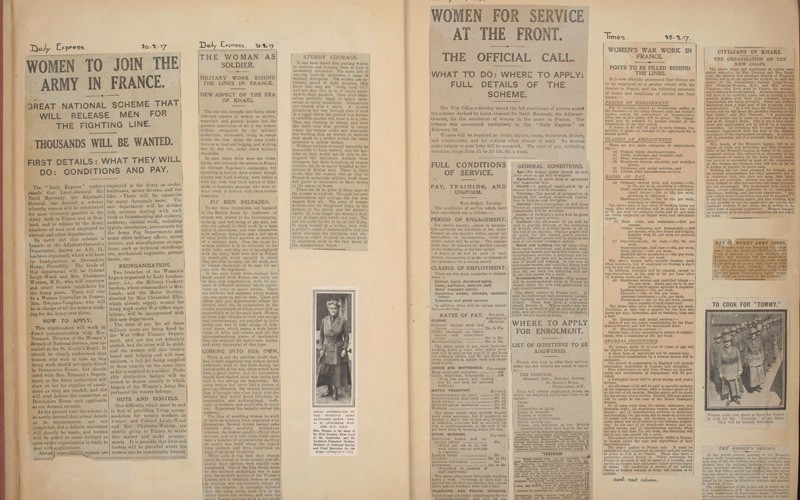

On 16 January, Lawson delivered to Parliament the findings from his trip, also recommending that women should work with the Army in France. In February 1917 the press announced that women were heading to the front and Florence was made Controller of Cooks in the new service.

More details: NAM. 1998-01-78-25

A month later the first women arrived on the Western Front. They were employed in a variety of jobs. As well as cooking and waiting on officers, they served as clerks, telephone operators, store-women, drivers, printers, bakers and cemetery gardeners.

The Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) was formally instituted in July 1917. Florence brought her 7,000 cooks of the Women’s Legion under its control and became controller of recruiting.

In February 1918, she replaced Mona Chalmers Watson as Chief Controller of the WAAC. Impressed by its excellent conduct, Queen Mary became a patron of the service in April 1918 and it was renamed in her honour. By the end of the war, nearly 40,000 women had enrolled in the Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps (QMAAC). Of these, some 7,000 served on the Western Front.

‘No one who had known her can forget her personal charm, her exceptional good looks and her graceful bearing…’

In 1919, Florence was made a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE) for her wartime services, becoming the first military dame. She retired from the QMAAC in 1920, but following their disbandment in 1921 organised the QMAAC Old Comrades Association.

Florence and Henry divorced in 1920. She got remarried in 1922 to Ernest Percy Simpson, who died three years later in 1925. Florence, however, remained close to Ernest’s daughters, and lived with them in South Africa in later life.

In 1956, she became seriously ill, moving to a clinic in Arleshiem, Switzerland, to seek care. She died there, aged 81, on 5 September 1956.

Explore further

- Article: Other Soldier Stories

Explore the map for similar stories

Controller Florence Simpson - St Peter, Jersey

First World War in Focus

First World War in Focus