Following the release of her new book, ‘Somme: 141 Days, 141 Lives’, Alexandra Churchill (with co-author Andrew Holmes) explores the story of Lieutenant George Higginson, the commanding officer of a team sent to rescue 120 men left stranded on the Somme battlefield.

On 18 November, the final day of the Battle of the Somme, the 97th Infantry Brigade advanced across no-man’s-land in driving sleet, and headed for the German front and support lines on Redan Ridge. Despite some men reaching the enemy’s positions, they were too few in number to hold them. By dusk all the remaining soldiers had been pushed back, or so it was thought.

On Redan Ridge, unknown to the British, a party of 120 men still held a portion of Frankfurt Trench and remained there in isolation, with the enemy completely unaware of their presence. This didn’t last for long. On 20 November 1916 the Germans launched their first attack, which was beaten off by the beleaguered troops.

The following day a non-commissioned officer and one of the men from the trapped party broke back through enemy lines and alerted the British to their predicament. An attempt later that night to bring back the marooned troops failed, as the rescuers were unable to breach the German front trench.

By this time, the occupiers had run out of food and rations. Some of the stranded men volunteered to go out into no-man’s-land to take supplies from the bodies of dead soldiers. A second German attack was repelled on 23 November, although by now the situation for the stranded men was becoming perilous. Over half of them were wounded and the lack of supplies was becoming desperate.

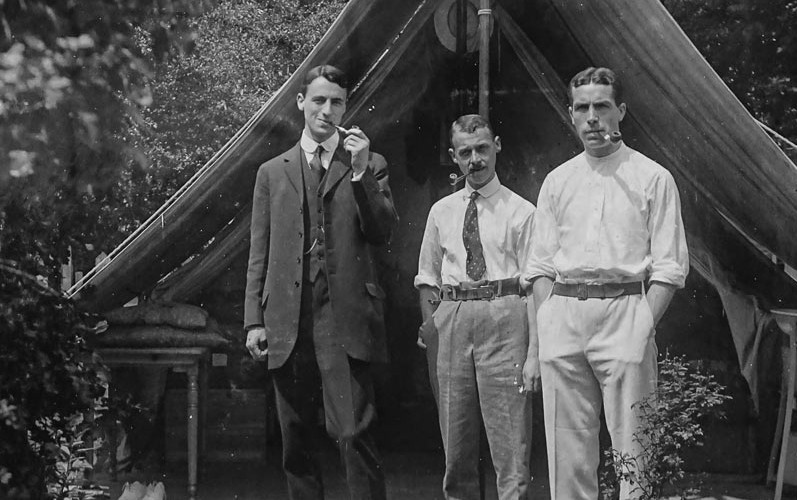

Lieutenant George Higginson was a 28-year-old teacher from Worcestershire who enlisted at the outbreak of war. Until his commission came through in December 1914, George underwent training with the 19th Royal Fusiliers at their camp in Woodcote Park, Epsom. The battalion eventually landed in France in September 1915.

Less than two months later, George was injured by an explosion during grenade instruction at Bayonvillers on the Somme. The extent of the wounds to George’s right arm were so severe that he was evacuated back to Britain for treatment. After leaving hospital, George was transferred into a different battalion of his regiment.

George returned to the front line on 19 November 1916, joining the 16th Lancashire Fusiliers as they moved into the British lines opposite the isolated men in Frankfurt Trench, the original German support line. After the trapped mens’ failure to break out from the German trenches, it was decided that another rescue attempt should be mounted by 300 men. George would command the third wave of troops, who would push on through the initial attackers towards the Frankfurt Trench and rescue the stricken British soldiers.

Zero hour was 3.30pm on 23 November. George and his Lancashire Fusiliers, along with the 2nd Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, advanced under the cover of an intense artillery barrage. Initial progress was encouraging. Munich Trench, the German front line, was reached and occupied without too much opposition, but then the Germans emerged from their dug-outs to launch counter-attacks against the British. Fierce fighting at close quarters took place.

Despite the ensuing struggle, George and some of his men managed to cross the Munich Trench and head towards Frankfurt in search of their trapped comrades. But no further progress towards the stranded men was made.

On 29 November, George Higginson’s widowed mother received a telegram from the Army stating that they had received information that George had been wounded, and the authorities began making enquiries.

Statements were taken from seven soldiers who attacked alongside George. The contradictory nature of some of these statements revealed how difficult it was to accurately recall events that took place under extreme conditions. Accounts contradicted each other hugely as to what had happened to him. Finally, a Sergeant Holt said that Higginson was between the German first and second lines when he was hit by machine-gun fire. When Holt went to his assistance he found that George was already dead and so he dragged him into a shell hole and covered him with a waterproof sheet.

On 20 March 1917, the War Office wrote again to George’s mother, sending their deep regrets, but stating that they believed he had been killed somewhere between Munich and Frankfurt Trenches on 23 November. George’s body was recovered and he was laid to rest in Waggon Road Cemetery.

The men stranded in the German trench were never rescued and managed to hold out for another couple of days. By the time that they came to surrender, after another severe enemy attack, only 15 unwounded soldiers were able to stagger out of Frankfurt Trench and hand themselves over to the Germans.

First World War in Focus

First World War in Focus